Well, thank goodness. It was touch and go there for a while but it looks like autumn is finally – finally – putting in an appearance. Not that I’m in any particular rush for the cold and the rain. It’s just that before we know it winter will be upon us and there seemed to be a chance there that autumn was going to get somehow missed. What a shame that would be to skip what I think it the best time of the year for seasonal foods.

October’s piles of pumpkins must be one of the prettiest sights of the season. Whatever the weather there’s no way of missing those. Lantern-carving fun aside I go in for eating the flesh as a spiced soup, mashed as a partner to some good meaty sausages or baked with orange zest and rosemary. There’s pumpkin pie, too, which is mostly thought of as an American dish but – much like the carving of the lanterns – its heritage lies with the other winter squashes that are the pumpkin’s British relatives.

Norfolk’s old recipe for Million Pie is a pastry crust filled with the sweetened and spiced mash of one of the many other squashes that would have been around in the 16th century at this time of year.

Our modern grocers are happily getting better at offering up a wider variety of squashes again than just the old-faithful butternut and pumpkin. Keep an eye out for the glorious variety of shapes, sizes and colours that run the gamut of our gourds.

They are a rather more attractive option than the root veggies that are also abundant in October. Although what turnips, salsify or parsnips lack on the looks front they make up for with flavour. Those farmers who feed their parma pigs with parsnips for the sweetness that the veg gives to the meat know what they’re doing.

Parsnips have a versatility that backs up their place as a mainstay of the British diet before potatoes nudged them out of the way. They’re terrific when chipped, crisped, mashed, roasted, baked, braised, or stuck in around a roasting joint to soak up the delicious meat juices. I’ve found a lovely recipe for parsnip mash which mixes the mashed veg with a shot of madeira, twice as much cream, a knob of butter and seasoning. That’s then baked for 20 mins in a high-ish oven (190C) with butter dotted on top and a small handful of chopped walnuts scattered over. Try it with some roasted game or a pork chop.

I’m also rather keen on this parsnippy take on the croquette. Just in case that sounds a little too 1970s take comfort in the knowledge that its origins actually lie a good hundred years or so earlier than that.

Deep-fried parsnip cakes (makes approx 8)

- 800g parsnips, peeled and cut into inch pieces

- 70g butter

- 2tbsps double cream

- half a nutmeg

- 1 egg, beaten

- 100g breadcrumbs

- 1l vegetable oil for deep frying

1. Steam the parsnips for about 20 mins until tender.

2. Melt the butter and add to the parsnips with the cream and a good few gratings of nutmeg. Season and mash thoroughly. Allow to cool before shaping the mashed parsnip into golf-sized balls or longer croquettes as you prefer. It helps to keep them intact when fried if you have the time to sit them in the fridge for an hour or so once shaped.

3. Heat the oil in a medium size pan. It needs to hit 180C but also test with a few breadcrumbs. They should sizzle when thrown in (if they burn you’ve gone too far and need to let the oil cool down). Roll each cake first in the egg and then in the breadcrumbs before putting into the oil to fry in batches until golden – approx 5 mins. Drain on kitchen towel as you take them out and keep warm until finished.

They’ll be crispy and crunchy on the outside but meltingly sweet and comforting on the inside. Very good alongside roasted goose that there’s really no reason to wait until Christmas for.

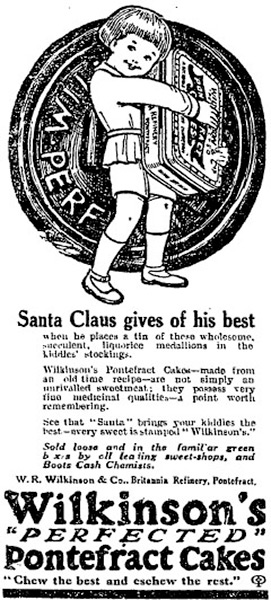

This talk of autumn roots brings another to mind. A plant without which there’d be no Bertie Bassett. Imagine that. Bootlaces, sherbet dips and Pontefract Cakes similarly each owe their place in British tooth decay history to the liquorice root industry which Yorkshire was once at the heart of. There’s something rather special about the soil round there. Much like the Yorkshire forced rhubarb ‘triangle’, it’s the only region of the country where the ground is suitable for growing liquorice. The roots of that (pun intended) go back a thousand years and the shame is that by the end of the 19th century the liquorice industry was proving unsustainable and collapsed.

This talk of autumn roots brings another to mind. A plant without which there’d be no Bertie Bassett. Imagine that. Bootlaces, sherbet dips and Pontefract Cakes similarly each owe their place in British tooth decay history to the liquorice root industry which Yorkshire was once at the heart of. There’s something rather special about the soil round there. Much like the Yorkshire forced rhubarb ‘triangle’, it’s the only region of the country where the ground is suitable for growing liquorice. The roots of that (pun intended) go back a thousand years and the shame is that by the end of the 19th century the liquorice industry was proving unsustainable and collapsed.

These days most of our liquorice roots and extract come from Italy or Turkey. There is one Yorkshire farm trying to reinvigorate the region’s commercial liquorice heritage.

Let’s hear it for Rob Copley. He has got a few years to go until he has a meaningful harvest and once he does around now is the time when it would be harvested. Liquorice’s spicy sweetness feels right in autumn. The extract is what you need if you have any designs on cooking with it. Anna Hansen sells it as a paste online and from her Modern Pantry restaurant in east London. Might tempting it is too to add a little into anything chocolatey (puddings, cakes, ice-creams, sauces…), with figs, or grilled meat recipes. Bageriet in Covent Garden sell a liquorice and raspberry jam that makes a good excuse for visiting one of the cities’ best cake-houses.

The liquorice roots which can be bought at high-street health food shops will be coming in particularly handy soon as sticks for toffee-apples. More on that next month as the ‘Culinary Calendar’ will be going Bonfire Toffee-tastic.