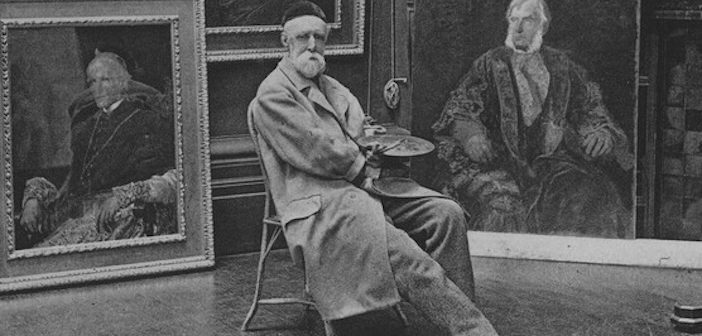

Before art was branded, filtered, or farmed for clicks, one man insisted it was a question of the soul. George Frederic Watts did not paint to soothe – he painted to warn. Douglas Blyde ventures to his gallery in Surrey to uncover what maketh the man…

The first thing to grasp is this: he meant it – every stroke of the brush, every push of pigment, each purposeful gesture not a flourish but an act of resistance, a muscular refusal to bend to fashion or flattery or fame. George Frederic Watts didn’t paint to please. He painted to withstand. His work was a rejection, deliberate and furious, of the creeping triviality he saw settling like dust over the culture around him – a culture already beginning to trade truth for novelty, depth for dazzle, substance for spectacle. He foresaw what we now inhabit: a world barrelling toward speed, simulation, and superficiality, and he stood in the middle of that oncoming storm like a prophet with a palette, a man for whom painting was not a profession but an act of moral insurgency.

Europa and the Bull, GF Watts (1860s)

Watts believed in the soul – not the airbrushed abstraction peddled from pulpits or party conferences, but the real thing: the bruised, incandescent, unkillable core of what it means to live and feel and be. What he gave us were not likenesses. They were confrontations. These were not polite portraits to flatter lineage or reassure wealth. They were storm-maps of human interiority – each canvas a meteorological record of some invisible squall tearing through the sitter’s spirit. The eyes accuse. The silence is weighted. The paint, at times, feels scorched.

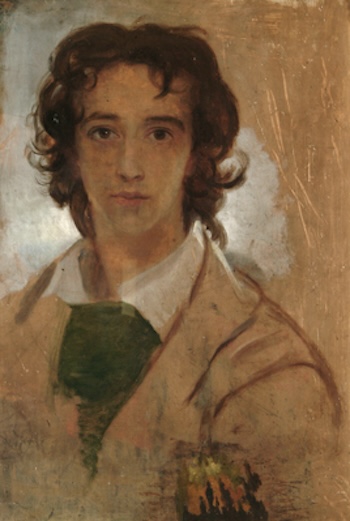

GF Watts, self portrait aged seventeen (1834)

Watts was born in Marylebone in 1817 on the birthday of Handel – his namesake. He was the son of a poor piano maker, delicate in health, motherless by nine, raised under a flinty Christianity which put him off organised religion for life. But he was fed Homer, not penny comics, nor hymns, and it was the Iliad, not the epistles, which carved his mental scaffolding. At ten, he was learning sculpture. At eighteen, enrolled at the Royal Academy. At twenty-six, he won the Westminster mural prize with a vision of Caractacus in chains, and briefly imagined London’s Parliament covered in the moral frescoes of civilisation. It never happened – but the ambition never left. He called it his ‘House of Life’: a symbolic cycle which would trace the long arc of human emotion, aspiration, suffering, spirit. A visual mythology for a modern soul.

He travelled to Italy. He inhaled Michelangelo. He sat beneath Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel and came away changed. In Tuscany he painted, frescoed, and studied the ancient techniques as if they were scripture. He returned to London a man marked. There were commissions. Portraits. Prizes. A stint among the Prinsep circle and a brief, strange marriage to Ellen Terry, 30 years his junior, which ended in estrangement and a quiet, conditional allowance. He did not remarry until he met Mary Seton Fraser Tytler.

Mary Seton Watts, Self-Portrait (1882)

Mary met him flame for flame. A Scottish artist and designer, she had her own radical grammar of form and faith. They married when he was 69 and she was 36 – not an arrangement of convenience, but a convergence of mission. Together they dreamed of a space for art which was not performance but philosophy. They called it Limnerslease – from limner, an artist, and leasen, to glean. It was both sanctuary and studio. His was equipped with a hidden mechanism which could lower vast canvases into the floor, allowing him to reach every edge of his moral epics. Hers was a workshop of tiles and colour, where her commitment to the Home Arts and Industries movement took on texture and shape. She trained villagers. She founded a guild. She carved belief into bricks.

They didn’t just build a home. They built a world.

The Watts Gallery opened in 1904, just months before his death. It remains Britain’s only purpose-built gallery dedicated to a single artist – and it isn’t a mausoleum. It’s a manifesto in brick.

And nearby, up a wooded slope, stands the Watts Chapel – the most extraordinary act of communal artistry ever given to the English countryside. A circular temple clad in Celtic and Art Nouveau ornament, it was Mary’s creation, brought to life by the hands of 74 local villagers whom she trained in modelling, gilding, and terracotta craft. Each had a task. Each left their mark. At the altar, three months before his death, Watts added his final painting: The All-Pervading. A vision not of comfort, but of consequence.

Watts Gallery (photo by Chris Lacey)

Before sanctuary, there was outrage. Watts used paint to accuse. Found Drowned, The Irish Famine, The Song of the Shirt, Under the Dry Arch – these are not scenes of hardship gilded with pity but are indictments. They are laments so furious they blister. Found Drowned, inspired by Hood’s Bridge of Sighs, shows a girl thrown from Waterloo Bridge – cruciform, discarded, the water already beginning to take her. A locket rests near her hand. A solitary star blinks through the industrial fog. The city, as always, looks away.

Print after G.F. Watts’s Painting ‘Hope’ (1885) by Emery Walker (1913)

Hope – perhaps his most misunderstood work – shows a blindfolded girl perched on a shattered globe, playing a harp with one string. This is not a dream of uplift. It is what endurance looks like at the very end of faith. Obama once referenced the painting during a campaign sermon, turning it into a metaphor for resilience. But Watts’ Hope was never designed for slogans. The girl cannot see. The world is broken. She plays anyway. It is not hope but defiance in despair.

He refused to sell these paintings because some truths are too raw to be owned. To hang one beside a drinks trolley would profane it.

They were made to disturb, not to decorate.

But fury cannot paint forever. At some point, it must metamorphose. So, Watts turned to allegory – not as retreat, but as escalation. In Time, Death and Judgement, there is no sermon, no celestial fanfare – only the stillness of eternity, and the terrifying possibility that one day we will each be asked, not what we made, but what we looked away from.

His portraits were not records but reckonings. Darwin bows under the weight of knowing. Tennyson, half-vanished, already part ghost. These faces do not flatter but confess.

And sculpture. Physical Energy – the equestrian colossus he began in 1883 and worked on until his death – was never meant to honour a man. It was meant to honour striving itself. No saddle. No flag. No destination. Just motion, eyes fixed on the unreachable. A monument not to empire, but to effort. ‘A symbol,’ he called it, ‘of that restless physical impulse to seek the still unachieved in the domain of material things.’

GF Watts, Full-Scale Gesso Model for ‘Physical Energy’ on display in the Sculpture Gallery, early 1880s-1904, gesso grosso

He proposed the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice to commemorate ordinary people who had died saving others. When the Crown declined, he paid for it himself. Postman’s Park still holds the wall of ceramic epitaphs. No glory, no fanfare, just the honest weight of unnamed goodness.

Mary was not just beside him in those last years – she was in every brushstroke. In every refusal to pander. Her chapel, her gallery, her guild – all of it was built with his spirit and her hands. They are buried next to each other because history could not bear to lie. To separate them would be to fracture the truth of what they made together: a kind of shared ethics in brick and blood. It was not a marriage of manners. It was a politics.

So yes, this is a love story. But not a gentle one. It is built from stubbornness, righteousness, and that rare thing: an unwillingness to lie about beauty. Watts did not want to soothe us. He wanted to jolt us into reckoning.

And today? We scroll. We pose. We curate. Our griefs are captioned. Our convictions filtered. We live not in a culture of beauty, but in a marketplace of self-myth. We mistake quantity for worth. We outsource meaning to algorithms. We bury the soul in likes and latticework branding.

Watts would have been appalled – not just by the content, but by the carelessness. He would have stared through the screen and asked what the hell we thought we were doing, watching ourselves vanish beneath an avalanche of content without content. He would have stood, once again, in the road. And painted.

He asked, without irony, whether beauty could still be righteous. Whether it could tell the truth, even when we didn’t want to hear it.

He answered with his work.

Now it’s our turn.

What will we make which cannot be monetised?

What survives when the feed dies?

What, when the algorithm forgets us, will still speak?

Watts Gallery, Down Lane, Compton, Surrey, GU3 1DQ. For more information, including details of creative workshops, and its current exhibition ‘Scented Visions: Smell in Art 1850—1915’, please visit www.wattsgallery.org.uk.

Images courtesy of Watts Gallery Trust. Gallery photos by Chris Lacey.