Photojournalist and Sports Photographer Jon Nicholson has as many stories to tell as he has photographs. In a 37-year career, to date, he has documented icons and iconoclasts, captured signature moments in sporting history and heart-wrenching human catastrophe. In this digital and smartphone age, much of his work represents a lost art in photography.

A retrospective exhibition, ‘Pausing for Breath’, marking the 25th anniversary of his iconic image of Ayrton Senna (taken the morning he was killed), is currently on show at the Augustus Brandt gallery in Petworth, West Sussex. The Arbuturian went along to hear him talk through his career and some of the stories behind his images…

We begin as Jon shows us a collection he calls his ‘heroes’, featuring not simply those from his years as a sports photographer, but of the many people he’s met and photographed on his travels.

You obviously have an ability to see the heroic in all kinds of situations, can you tell us a bit about your journey and what, to you, constitutes a hero?

I call these images my ‘heroes’ because all of the people I’ve taken in the collection are heroes to me, and for many different reasons.

I started as a sports photographer and that was my dream. But I didn’t want to shoot just cars flying round corners or people running, I wanted to show the documentary aspect, I wanted to shoot behind the scenes, so accesswas absolutely key to what I wanted to do. As I grew through my career, capturing more photojournalism work, my ability to bond with people gave me the access to be able to take pictures. Taking pictures is easy, it’s the access that’s the hard part.

How do people treat you then? What do they think of your presence in their environment?

When I started doing Formula 1 with Damon [Hill], that was easy because he was my mate and we’d had a childhood dream that he would win the championship and I’d be there to take his picture. In 1994, the year Ayrton Senna was killed, as well as documenting him and the circuit, Damon and Michael Schumacher battled tooth and nail for 8 months that year, it was a year I captured some great work, and everyone else that I knew in sport thought ‘if it’s all right for him, it must be all right for us’, so they all started to open the door to me.

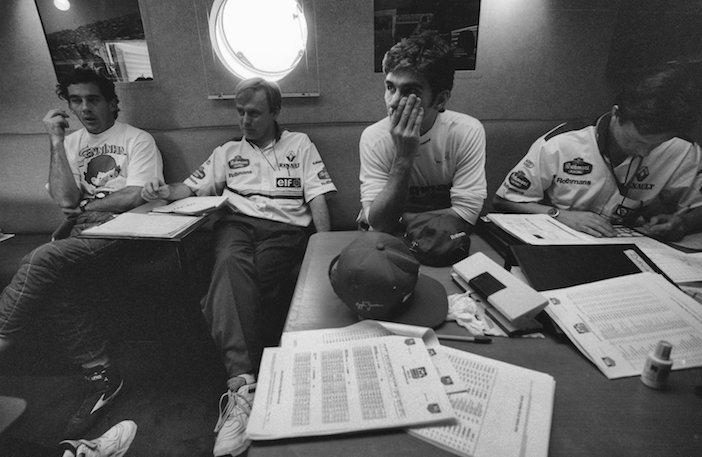

Ayrton Senna, left, with Damon Hill (centre right) and two race engineers. Sunday morning, 1st May 1994, Imola San Marino GP. In Jon’s words, “Here Ayrton kept saying how he didn’t want to race, that he was being made to…two hours later he was dead.”

What was your most challenging shoot in sport, would you say?

It was back in the beginning, for that shot with Linford [Christie] running across the lava fields in Lanzarote. It was 1992, just prior to the Olympics, and he was training there at the time.

I went out there, and he kept me waiting for three days. Each day I’d go to meet him, waited for him, and nothing. On the third day, he comes over to me and says, ‘So what do you want to do?’ And I got up and walked off. I wasn’t going to let some sprinter get one over me.

I went back to my hotel room and thought, ‘I’m going to give him an hour’. Fifty-two minutes later, the phone goes, and it’s Linford inviting me for dinner. I went, we talked about the picture, and I told him what I wanted. He says, ‘fine, I’ll give you fifteen minutes’. I thought, ‘blimey’, so I got up at the crack of dawn, drove down to the location, timed what I wanted, got back in the car and back to the hotel. 9 ½ minutes.’

Then the time came, I picked Linford up, we sped down there, got the pictures, and I said to him, ‘Come on, get in the car, we’ve got to go’. And he said, ‘no, wait, I’ve never been here, this is amazing.’ We stayed there an hour and a half, talking about nothing to do with photography, athletics, or anything. That then formed a bond such that during the Olympics, he would call me before a race. He just wanted to talk to someone unconnected. We’ve since done two books together. We’re still friends.

So that’s what it’s about. It’s not about taking the picture, it’s about the trust of being allowed in, forging that relationship, then getting the pictures.

How does that translate into your African experiences?

Well, when I was doing the sports thing, I thought I was the best thing since sliced bread. I was 23. But, reading the papers, I soon started turning from the back pages to the front, and reading about food crises, HIV, and all those horrific things. Then I met a lawyer for UNICEF, we got chatting and he said, ‘you’ve got to come and do some stuff for us.’

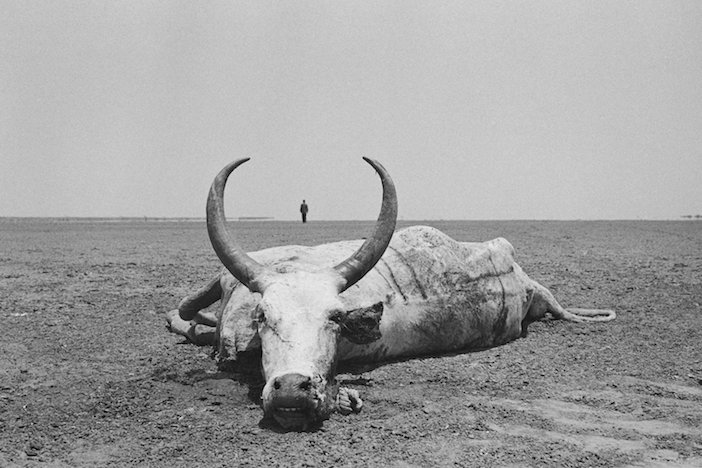

This was, for me, the next stage of my career, so we set out on a project to document the circumstances and spread of AIDS affecting Africa. [Jon points to various pictures on the walls] These relate to the famine in Ethiopia. The shot of that man and his cow on the flats; his cow dropped dead and he just walked off into nowhere. This image [he points to the mother and child], this kid; chronic diarrhoea, everything going wrong. Horrible. The first thing the doctors do is test him for HIV, but then they can’t because they don’t know if that’s his mum. So, you’re into all these issues. Anyway, they tested the kid, and he was positive. So, the child was going to die because the malnutrition had accelerated the issues contributing to HIV. It’s a beautiful, loving picture, which makes it all the more tragic. But, in all these pictures, I’m also trying to capture hope.

How do you cope emotionally?

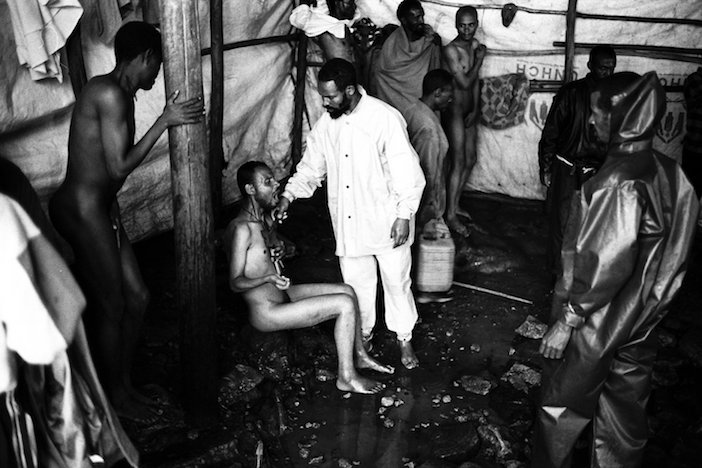

It’s hard, it’s really hard. I used to wear sunglasses everywhere. At the time, you put your feelings to the back of your mind; you detach while you can. It’s not just horror either, there’s anger too. [Jon shows a series of images of a man in white seemingly helping people]. This guy professed to be able to cure AIDS. This was in the hills above Addis Ababa. I was in the UN office and someone came in and told us about him, so we went up there. And this is where egos come in. He’s thinking I’m either going to expose him, or embrace what he’s doing, and you can only gauge that when you look someone in the eye. Has he got a gun? Or is he going to open his arms to you?

So, I told him, ‘You’re the only guy on the planet who could cure AIDS, how amazing are you? Surely you want the world to know that?’ Then he wantedme to take the pictures. You have to play that game to get in. We had about two hours to get these pictures, and then he suddenly turned. He became very aggressive, and the security with me told me it was time to get out.

So, these situations created anger. These people all leave this man, thinking they’re cured, carrying on sexually, and it marches on.

It’s difficult to get perspective on it. But that…then leads to Darfur.

What happened in Darfur?

I’d met a great hero of mine, Don McCullin, and he’d been in Chad, next door. His pictures were all right, nothing special; kids with drips and refugee camps, but they were lacking. And I said to him, ‘Don, you didn’t get in there, you didn’t produce the goods.’ So, I thought I’d go. I contacted the UN and asked to go out there. They thought I was mad, but they agreed. I got there, and told them I had the Sunday Times on board, an exhibition in the West End, and said I needed access. I was going to photograph all the feet of those women who’d walked to freedom.

They enjoyed that, me photographing their feet. And then, as they stood up, I photographed their clothes, the idea being to form this composite image. It was an image of the clothing of the women had removed so they could be raped. Because that’s what happened. These villages were attacked, the men hung upside down and slit open from top to toe, and the women raped. Again and again. But my idea was to try and show it in a way that wasn’t shocking photojournalism. We’d seen all that and people had had enough death and misery. So here I printed these images, beautiful images…and then you read the story. I wanted to shock people into understanding the story.

They enjoyed that, me photographing their feet. And then, as they stood up, I photographed their clothes, the idea being to form this composite image. It was an image of the clothing of the women had removed so they could be raped. Because that’s what happened. These villages were attacked, the men hung upside down and slit open from top to toe, and the women raped. Again and again. But my idea was to try and show it in a way that wasn’t shocking photojournalism. We’d seen all that and people had had enough death and misery. So here I printed these images, beautiful images…and then you read the story. I wanted to shock people into understanding the story.

This lady [he approaches an image of a woman in close up, looking through a veil]…this lady’s village was attacked. Her husband and son were murdered. She stayed in the village. Three months later the village was attacked again. At that point she ran. She ran and ran and ran and ran. She ran until she collapsed. She woke to find wild dogs eating her miscarriage. She then got up and ran again, until she got to safety. I’m in that shot, reflected in her eyes.

You ask me how I cope with that, as she’s telling me her story? From taking that photograph, I flew back to Khartoum, transferred to Jordan, and was on a flight to Nice in a matter of hours. I got to Nice, got picked up by a car and taken to the Café de Paris for a dinner at the Monaco Grand Prix. I’d had just enough time to shower, put on a suit, and go to this dinner. I’m sat there eating and a lady sitting next to me says, ‘I say, you’ve got sand in your ears’.

You ask me how I cope with that, as she’s telling me her story? From taking that photograph, I flew back to Khartoum, transferred to Jordan, and was on a flight to Nice in a matter of hours. I got to Nice, got picked up by a car and taken to the Café de Paris for a dinner at the Monaco Grand Prix. I’d had just enough time to shower, put on a suit, and go to this dinner. I’m sat there eating and a lady sitting next to me says, ‘I say, you’ve got sand in your ears’.

How do you cope with that cultural shift?

It’s bloody difficult, but you can’t download it at a table at a fancy dinner. It takes years and years to process, and I still don’t think I have.

I was due to go back to Darfur and we were having some friends round, and one of them asked me what I was up to next and my daughter, without looking up, just said, ‘Daddy’s going to Darfur to get shot.’ And that was it, I said no more.

All of this, all of these pictures are really sad. But it’s necessary.

For all the risks, has there ever been a moment you could have been killed?

When I was in the Sudan, a guy standing next to me was shot. We were in the middle of nowhere, there was a crack and you could hear the bullet whistling towards us, and it hit him. A little bit of wind and it could have been me. In Darfur I nearly got hit by an RPG. The risks come when they know you’re coming, they know why you’re there and they see an opportunity.

When the pictures are published, or seen in an exhibition, do you get a sense of their impact on people? Is there a wider, social impact?

Once the Darfur pictures had been in the Sunday Times, they got used all over the world. We then did the exhibition I mentioned, and then something extraordinary happened. George Clooney rang me up. He and Matt Damon were starting a campaign about human rights called Not On Our Watch, and asked if they could use the pictures. I said absolutely. So, they’ve used them, and then since, over the years, a lot of universities have taken them because they’re an education about Darfur.

As the world changes, and Africa in particular is undergoing some extraordinary development, do you get concerned your photographs would reinforce a certain stereotype?

At the time, particularly with HIV, I was concerned. But not now; but then the last time I was in Africa was about 10 years ago. But then people don’t want these stories any more; people don’t want to look at them and people don’t run them.

Why’s that, d’you think?

It’s because technology has changed. The photojournalist is yesterday’s model. With digital phones and social media, everything has changed. A mass onslaught of people taking images thinking they were great photographers, but knowing nothing about the issues, let alone how to use a camera. Or trying to get access, or bonding with their subject. And it’s just fuelled the cult of celebrity. Take the Sunday Times magazine. The greatest photojournalism magazine in the world up until about ten years ago. Not any more. You could rely on the Sunday Times to deliver a good story, now it doesn’t’ happen. So, we’re looking elsewhere for a good story.

All of my work on these walls was used. Yes, it was commissioned but it also had corporate backers who wanted to get it out there. It meant I had exhibitions in the UN, and in every country in Africa, to educate people and make them aware.

With the demise of the Sunday Times magazine, and the likes of Life magazine, what are the ways now of getting the stories out?

Good photography should be seen. And situations need to be photographed. Street photography and documentary photography is incredibly important because it shows the history of where we are. I did a project a few years ago in the Square Mile. Fifty years ago it would have been bowler hats and brollies, no women, no diversity, no restaurants. Now Cannon Street has a restaurant for every country’s cuisine. Come out of Bank station and you’ll see a girl in her running gear, a muslim lady coming out of the tube. It’s what we expect now, and pictures need to be taken to record that.

Good photography should be seen. And situations need to be photographed. Street photography and documentary photography is incredibly important because it shows the history of where we are. I did a project a few years ago in the Square Mile. Fifty years ago it would have been bowler hats and brollies, no women, no diversity, no restaurants. Now Cannon Street has a restaurant for every country’s cuisine. Come out of Bank station and you’ll see a girl in her running gear, a muslim lady coming out of the tube. It’s what we expect now, and pictures need to be taken to record that.

At the same time as doing all this [he gestures on the walls to the Africa pictures]I was also doing the nice projects. I started my cowboy project and I went off and did a lot of work for Nat Geo, among other things.

You’ve got a huge breadth of work, not just the tragic and distressing. There’s humour, too. The monks walking past the Gucci store, for example.

Yes, in those you look for juxtaposition. And irony. You can try too hard to go out and get those; those sort of pictures just appear but, again, it’s all project based.

What was the cowboy project you mentioned?

It’s a real labour of love for me, a real passion. I was doing a project for Wrangler jeans, and working with this cowboy at these little rodeos in the countryside just outside Tulsa. The project was actually about the culture of Buckle Bunnies, essentially cowboy groupies.

It was while I was doing this, there was one guy who I got talking to who just started spouting all these issues about the decline of ranching and rise of ranch monopolies, even the rise of veganism, various things, and I came away thinking there were going to be no more cowboys. So, I made a few trips back just to see what the story was and got talking to a publisher who commissioned a book about them.

That was about five years ago and now there are a lot of climate change issues that are affecting their lifestyle and livelihoods, particularly in the South West, so I now want to go back and capture their vanishing world. I’ll do a lot digitally, too.

So, what were you shooting previously?

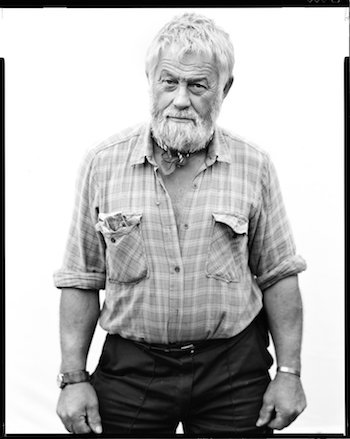

All sorts. A lot of these cowboy portraits are 5×4 and 10×8. But everything I do, in the research to projects, it’s all homage to photographers who have gone before. This [shows a portrait]is shot 10×8 with a white background. It’s a homage to Richard Avedon. In the 70s and 80s he was commissioned for a series of photographs called In the American West. Avedon was a fashion photographer, a portrait photographer. He lived and worked in New York and never went outside his studio in 40 years. And what he did was photograph the drifters, the cowboys, the people, notthe landscape. When the museum that commissioned him saw the first set of pictures they went nuts because, obviously, they wanted The Grand Canyon by Richard Avedon. But that body of work has now become the definitive; Avedon: white background, Bailey: white background, Nicholson: white background.

All sorts. A lot of these cowboy portraits are 5×4 and 10×8. But everything I do, in the research to projects, it’s all homage to photographers who have gone before. This [shows a portrait]is shot 10×8 with a white background. It’s a homage to Richard Avedon. In the 70s and 80s he was commissioned for a series of photographs called In the American West. Avedon was a fashion photographer, a portrait photographer. He lived and worked in New York and never went outside his studio in 40 years. And what he did was photograph the drifters, the cowboys, the people, notthe landscape. When the museum that commissioned him saw the first set of pictures they went nuts because, obviously, they wanted The Grand Canyon by Richard Avedon. But that body of work has now become the definitive; Avedon: white background, Bailey: white background, Nicholson: white background.

So, I like to play that game with where I go. When I went to the cowboy thing, there was a guy years ago whose nickname was ‘Cowboy with a Camera’ and he used glass plates and tripod and he took this cumbersome kit strapped to his horse, and I did exactly the same thing. I wanted to experience what it was like. It’s a hat tip to the past.

A lot of your work is wonderfully spontaneous, how do you capture those?

Conversely to that cowboy stuff, I don’t usually like carrying loads of gear, it’s just two Leicas, one colour and one black and white, two lenses and off I go. It allows you to be very flexible, very spontaneous. Also, I don’t look like a photographer. I’m not carrying a massive lens!

And I tell you what it is, rather than stand on the opposite side of the street trying to photograph a 90-year-old woman selling pineapples, why not cross the road, eat one of her pineapples, and talk to her. And she’ll say, ‘come and meet my husband’, so you go around the back and there’s her 100 year old husband serving beans on toast to their 40 kids. That’s your picture!

More recently, you’ve done a lot of ‘painted’ work, is that a departure for you?

It’s an evolution from my work. I was coming back from a trip and just thinking, ‘What am I going to do with my work?’ I had a picture I took, it’s a black and white Hasselblad [he shows a shot of a young man and woman in Tokyo]where I took her out of it and put her onto a composite background I’d made, and then I painted it with the iPad. All of these with a bit of colour to them to were done on an iPad. It was a bit of fun and then, when I printed it up, I thought ‘wow, that’s very Warhol.’ I mean, it’s got to hold up, and it does. This cowboy, for example, is an absolute rip-off of Warhol’s Elvis picture, but it works. We’re in a time now when everyone’s doing all sorts of things, so you have to try and be a little more creative.

And that’s what you’ve done with your Brexit picture…

Yeah. All the images came from a project I’d done with the City of London Corporation and the day we got that Evening Standard headline ‘We’re Out’, they pulled the plug on the project. So, earlier this year, when the deadline was looming, I was getting really angry with everything, so I just pulled all these pictures together and created this collage. And it’s meant to be catastrophic, that’s the point.

Do you know when you’ve got a good photo?

I’m glad you asked that. Yes, you do. [He pulls up a photo of a boy monk] Let me tell you this story. This monk…I’m in my last day of a trip in Laos and my guide suggested we go to a place called Lucky Island, in the middle of the Mekong in the middle of nowhere. There’s a little monastery with about a dozen monks there. We’d done a few shots and we’re taking break; I’m sitting on a wall talking to my translator and you know when you’re aware of someone sitting next to you, without seeing them? This boy had sat down. I glanced round and he’s sitting there, just like in the picture, against a white pillar. And he’s just looking at me, he didn’t move. So I turned back, quietly switched the lens on the camera to the 50mm, turned and lifted the camera up in one move, and ‘click’.

I’m glad you asked that. Yes, you do. [He pulls up a photo of a boy monk] Let me tell you this story. This monk…I’m in my last day of a trip in Laos and my guide suggested we go to a place called Lucky Island, in the middle of the Mekong in the middle of nowhere. There’s a little monastery with about a dozen monks there. We’d done a few shots and we’re taking break; I’m sitting on a wall talking to my translator and you know when you’re aware of someone sitting next to you, without seeing them? This boy had sat down. I glanced round and he’s sitting there, just like in the picture, against a white pillar. And he’s just looking at me, he didn’t move. So I turned back, quietly switched the lens on the camera to the 50mm, turned and lifted the camera up in one move, and ‘click’.

Did he react?

He didn’t move. I looked down at the camera and thought, ‘that’s unbelievable’. I knew I didn’t need to take another, but I did anyway. It sort of then haunted me all day because I thought, ‘what a look.’ This kid is giving me every bit of knowledge he has. There’s worldly greatness going on there. So, he’s also a hero, as you can imagine.

How have you selected the images for the exhibition?

How do you distil 37 years into a single exhibition? You can’t. There are some that are a bit of fun, there are a couple of mistakes, admittedly. There’s a shot of three rocks upstairs. It’s a mistake. It’s shot in Cornwall, by the sea, and I saw this interesting rock. It’s shot on film and the film wouldn’t wind on, so it exposed the same rock three times, and when I developed it I thought, ‘wow, they look like planets’. I then thought that this was the anniversary year of the moon landings, and I’d met a guy called Eugene Cernan, who was the last man on the moon, so I got a picture of Apollo 17 and dropped it into that picture and created what you see now.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’ve been commissioned to do a year in the life of the Goodwood estate. I’ve known the Duke for years through the motor racing connection and it’s a great job because it’s never been done before, he’s always had painters. It’s quite an honour – and it’s nice not to have to get on a plane as well!

If you could pick one picture to save from the flames, so to speak, which would it be?

Oh, I hate this question. There are too many. If I really had to choose one…the boy monk.

Jon’s gallery talk was chaired by the journalist Charlotte Metcalf. ‘Pausing For Breath: A Retrospective’ is showing at the Augustus Brandt gallery in Petworth, West Sussex until 10thAugust 2019. For more information, visit www.augustusbrandt.co.uk and for more of Jon’s pictures, visit his website at www.jonnicholson.co.uk.