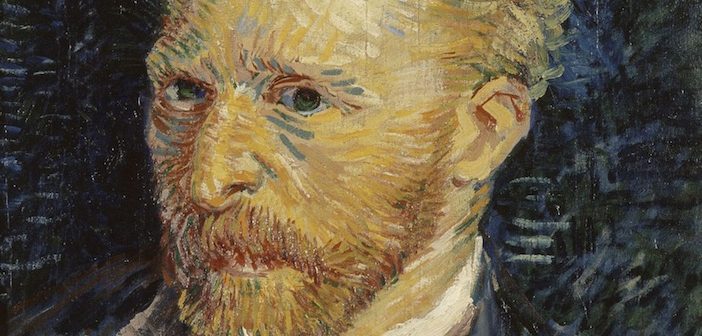

It’s an impressive feat to bring together 50 of Van Gogh’s works from private and public collections around the world, including such big hitters as Sunflowers (1888), Shoes (1886), Starry Night (1888), L’Arlésienne (1890) and three self-portraits. Yet despite this, the Tate Britain’s blockbuster exhibition doesn’t quite hit the mark.

Threaded with the theme Van Gogh and Britain, its first half explores how British culture, art and literature influenced the artist during three years spent here in his early twenties – first while working at the Goupil gallery, then trying short-lived careers as an urban missionary and teacher. The second half focuses on Van Gogh’s artistic legacy and his impact on British art.

Meindert Hobbema ‘The Avenue at Middelharnis’ (1689)

This nuanced approach widens the context of an artist who’s too often framed by his mental health – instead shedding light on his stylistic evolution, his subject choices, his keen social conscience and his passion for engravings. There are even some surprising revelations too, such as his love of Charles Dickens, whose Christmas Stories features prominently in L’Arlésienne. But the exhibition feels weighed down by its tenuous theme anchoring Van Gogh to Britain – and the joy of seeing his paintings is diluted by the volume of other artists’ work, which creates a frustratingly fragmented experience.

For better or worse, however, there is an impressive range of art on show. Meindert Hobbema’s The Avenue at Middelharnis (1689) is there, echoed by Van Gogh’s Avenue of Poplars in Autumn (1884), as are paintings by John Constable and Richard Parkes Bonington, and a pilgrimage by George Henry Boughton which Van Gogh labelled ‘not a picture but an inspiration’. Further along, a dusky Whistler nocturne of the Thames hangs beside Starry Night and is unconvincingly cited as an inspiration for the Dutchman’s mesmerising painting of Arles, where the night sky shimmers with cosmic lights and the Rhône is ablaze in reflections. As Van Gogh’s artistic identity evolves, the theme of Britain’s influence becomes harder to sustain.

However, if it’s challenging to identify who shaped his pioneering style, tracing Van Gogh’s impact on others seems easier – not least because it’s hard to imagine his work hasn’t entered the consciousness of most modern artists. This point is made to mixed effect in a flower-themed room, where Sunflowersglows in pride of place, stopping viewers in their tracks. The surrounding tribute of yellow flower paintings vary in resonance, however, with some acting more as a foil to the radiance of Van Gogh’s work.

In other places though, the connection is more powerful. Roderic O’Conor’s remarkable Yellow Landscape (1892) is a riveting descendent of Van Gogh’s lighter, softer Wheatfield (1888), while the final room is a crescendo of 20thCentury artists exuding his influence. Most striking is a tribute of three huge oil paintings by Francis Bacon, while David Bomberg’s stunning landscape Tregor and Tregoff, Cornwall (1947) burnishes with emotional intensity in Van Gogh’s gold and rust palette.

Vincent van Gogh, ‘Prisoners Exercising (Taking the Air in a Prison Yard)’. Moscow, Pushkin Museum

Nevertheless, the exhibition’s standout paintings are Van Gogh’s own, with The Prison Courtyard (1890) – on loan from Moscow’s Pushkin Museum – being a reason to visit in itself. While hospitalised during his final months and too weak to go outside, Van Gogh used this time to ‘translate’ prints into paintings, including Gustave Doré’s Exercise Yard at Newgate Prison (1872). He wrote of being crushed by the prison of hospital life, and his luminous painting is an enigma of hope and despair. Its shadowy prisoners trudge the circular path of a cramped prison courtyard, heads bowed in bleakness.

Yet drawing the eye upwards, their cold, blue treadmill gives way to sunlight that bathes the stonework above them in glowing colour. That same light falls upon a prisoner with a striking resemblance to the artist – at once framing his isolation and delivering a sense of hope that’s echoed by the presence of two butterflies high above, painted in Van Gogh’s signature yellow. It is aesthetically and emotionally superb. Inadvertently, it also mirrors the exhibition’s most vivid takeaway – that in a long line of artists, Van Gogh’s brilliance stands alone.

Although the exhibition’s delivery may disappoint, the abundance of Van Gogh’s work still makes it unmissable.

The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain showed at the Tate Britain (tate.org.uk) through the summer.