In a departure from our fiction titles reviews, retired army major Philip Cottam explores an altogether more topical, historical publication in our books coverage…

A year after the shambolic American-led departure from Afghanistan makes it a good moment to reflect on this tragic war-torn country. Hardly surprisingly, there have been many column inches on the failed American and British campaign and the current condition of Afghanistan after a year under Taliban rule. These have not, though, always paid enough attention to the ethnic, linguistic, and religious complexity with which any rulers of Afghanistan are always confronted. Anyone who really wants to get under the skin of the place and understand the impact of its position at both a geopolitical and cultural crossroads can do no better that start with Dr Jonathan Lee’s ‘Afghanistan, A History from 1260 to the Present’. First published in 2018 it has recently been republished in an expanded and updated edition.

Dr Lee possesses an intimate knowledge of Afghanistan and its people. Having first visited in 1972 he has garnered over 30 years of experience of not just Afghanistan but most of its immediate neighbours – Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. His time in the country has seen him involved not just in extensive academic research but also in aid projects ranging from support for refugees and well-being programmes for women and children to water management and supply. In short, he has seen the country from the ground up and this is reflected in his book.

Dr Lee possesses an intimate knowledge of Afghanistan and its people. Having first visited in 1972 he has garnered over 30 years of experience of not just Afghanistan but most of its immediate neighbours – Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. His time in the country has seen him involved not just in extensive academic research but also in aid projects ranging from support for refugees and well-being programmes for women and children to water management and supply. In short, he has seen the country from the ground up and this is reflected in his book.

Don’t be put off by its massive scale of the book and intense detail. Dr Lee reveals a treasure trove of extraordinary characters, political shenanigans, and madcap adventures alongside a clear-sighted explanation of how Afghanistan managed to become a state at all and survive to this day despite internal divisions and endless foreign interference. Perhaps most importantly, Dr Lee explains the history of Afghanistan through Afghan eyes and why so much foreign involvement – British, Russian and American – has been so disastrous and resisted with such determination.

Dr Lee addresses the complex ethnic, tribal, linguistic, religious, and socio-cultural make-up of Afghanistan as well as of the significance of its physical geography in his introduction. The country’s historic presence of Zoroastrian, Buddhist, Jewish, Hindu and Christian cultures was swept away with the arrival of Islam. These now represent a tiny minority of Afghans and are mostly visible through the medium of archaeological sites and the absorption of some customs into local culture such as the Zoroastrian lighting of lamps that still takes place in some parts of northern Afghanistan. Dr Lee shines his own light on the link between the principal religious divisions within Islam between Suni and Shia and how this sharpens the ethnic and tribal divisions that continue to bedevil Afghan society: the largest ethnic group are the Pashtun and they are Sunni, whereas the second most populous group, the Hazara, are Shia. Dr Lee’s superb introduction provides essential background to the shifting and swirling sands of the historical narrative that follows. It is worth buying the book for this alone.

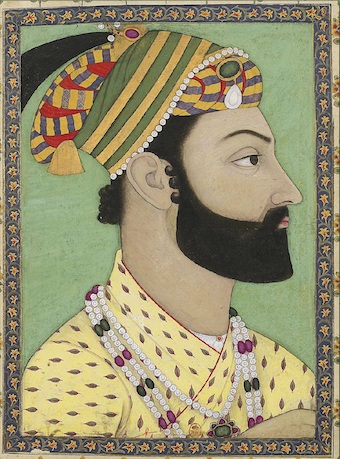

Portrait of Ahmad-Shah Durrani. Mughal miniature. ca. 1757 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

In the 18th Century Afghanistan did start to resemble something more than just a difficult outpost of someone else’s empire but it never became a unitary state on European lines. Its internal politics were dominated by tribalism and the importance of maintaining an acceptable balance of power between the different tribal groups. It also remained a battleground for others with the result that its external relations never seemed to escape from foreign interference whether the Russians and British in the 19th Century, the Russians in the 20th Century and the British and Americans more recently.

Unlike its neighbours Afghanistan never developed a real sense of nationhood. This remains largely true to this day. For all their own internal challenges, the ‘stans’ to the north – Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan – let alone Iran, India and Pakistan have all built the national identities that Afghanistan has yet to develop. The religious and ethnic divides remain too sharp and tribal and clan culture too deep. A serious attempt to develop a sense of national identity was made before the First World War by Mahmud Tarzi, known as the father of journalism in Afghanistan because of his newspaper Seraj al-Akbar. Influenced by the Young Turk movement in the Ottoman Empire, the movement which also influenced Kemal Mustafa Ataturk, Tarzi tried to develop what he called Afghaniyya – Afghanness or Afghanism. The problem was that Afghaniyya became increasingly identified with the Pushtu language and the Pashtuns with the result that it alienated non-Pashtuns.

Dr Lee ends his book with a review of events in Afghanistan since the turn of the century up to the departure of western forces in August last year. It makes for a sober and distressing read written as it is by someone with no political or ideological axe to grind. The list of failures is depressingly long: the lack of a truly coherent politico-military strategy; the endless corruption that undermined so many well-intentioned programmes; the double-dealing of the Pakistan ISI; the undermining of the Afghan government by the USA excluding it from their negotiations with Taliban; and finally the hasty, disorganised withdrawal. As for the future who knows? Most of the Taliban leadership are the old guard from the 1990s and, while they have made a temporary marriage of convenience with the extremist Haqqani network, the old tribal divisions remain and a local version of ISIS is growing in size and influence. For the people of Afghanistan, it does not look very encouraging.

Afghanistan: A History from 1260 to the Present by Jonathan L Lee is out now published by Reaktion Books.

Header photo by Mohammad Rahmani, copy photo by Wanman Uthmaniyyah (courtesy of Unsplash)