Looking at the soft-focus cover of Stranger in the Shogun’s City you might assume this is a romantic historical novel. It is, though, certainly no Tale of Genji set in the world of the Japanese feudal aristocracy, of the daimyo and their samurai warriors, let alone in the imperial court. It is, rather, the life story of a real woman in Japan in the first five decades of the 19th Century and it mostly takes place in the poorer parts of Edo, the city from where the shoguns governed Japan, or in isolated rural villages in distant provinces.

What gives the story particular resonance is that it ends just as Japan was to start to go through a period of dramatic change. Its protagonist dies in 1853 the year Commodore Perry sailed into Edo Bay with a squadron of four steam ships of the United States navy. His arrival not only precipitated the opening of Japan’s closed society to the wider world but also the overthrow of the feudal political and social order that provides the setting for this story and its replacement by a Westernised industrial society.

Tsuneno, the woman at the heart of this captivating book, is not your typical romantic heroine either, but the stubborn and difficult daughter of the prosperous Buddhist temple priest of the village of Ishigami. As a very young girl she was attracted by the exciting possibilities of town and city life and especially by the lure of Edo (now Tokyo), the political capital of the shogunate. This attraction was reinforced by a visit in 1829 to Kyoto, the home of the emperor and the imperial court. However, it was not until she was 36 and had been married three times – the first of these when she was only twelve years old – that she was able to fulfil her dream and escape to Edo.

Tsuneno’s life story has been painstakingly recreated by Amy Stanley, a scholar of Japanese and Associate Professor of History at Northwestern University in Illinois. She has benefited from the extensive correspondence Tsuneno and her family conducted and the copious records that still survive in the public archives. In doing so she has opened a window for us not only into Tsunano’s character and adventures but also into the way of life, and of city life in particular, of the majority of people in the final decades of the Tokugawa shogunate that ruled Japan from the battle of Sekigahara in 1600 to its final overthrow in 1867. Professor Stanley has also recreated the personality and atmosphere of Edo itself to such an extent that the city becomes almost as important a character in the book as that of Tsuneno herself.

Not long after Tsuneno arrived in Edo she contracted a fourth marriage albeit this time to a man of her own choosing. Even this marriage was difficult and included divorce and remarriage. Tsuneno’s new husband turned out to be as bad-tempered as she was but at least the marriage provided a degree of security. Life in Edo also turned out to be difficult. In one of her letters home Tsuneno wrote “nothing has gone the way I planned. I never intended to struggle so much.” Even so she lived in Edo for most of the rest of her life dying there in 1853 at the age of 49.

Not long after Tsuneno arrived in Edo she contracted a fourth marriage albeit this time to a man of her own choosing. Even this marriage was difficult and included divorce and remarriage. Tsuneno’s new husband turned out to be as bad-tempered as she was but at least the marriage provided a degree of security. Life in Edo also turned out to be difficult. In one of her letters home Tsuneno wrote “nothing has gone the way I planned. I never intended to struggle so much.” Even so she lived in Edo for most of the rest of her life dying there in 1853 at the age of 49.

The shogunate established by Tokugawa Ieyesu had brought peace after endless civil wars but at the cost of closing Japan off from most of the outside world and imposing a rigid feudal system under which the imperial family had a symbolic but largely powerless position. The new social order was influenced by Confucian ideas and based on the ‘Four Occupations’ of warriors, farmers, artisans and merchants. Once introduced these divisions became hereditary although as time went by there was a blurring of some of the lines of demarcation. The feudal aristocracy and the priesthood, whether Buddhist or Shinto, stood above and outside this structure. What this meant for Tsuneno was that she came from a family which, although not especially wealthy, had a respected social position in the village in which they lived. However, the social position of her family ceased to be of importance or of much help once she had opposed their wishes and become just another poor migrant looking for work in the busy, crowded and often cruel urban ant heap that was Edo.

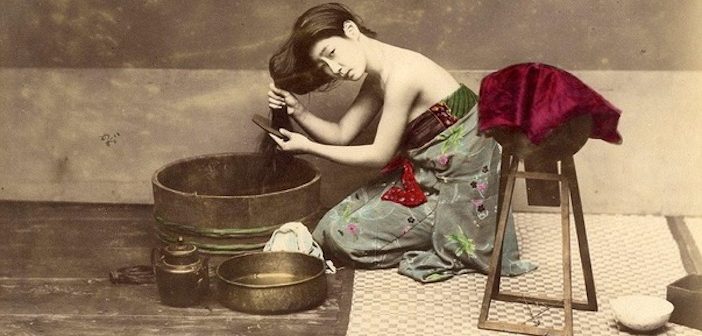

The role of most Japanese woman was prescribed and their role in the household was unaffected by where the household fitted in the social order. The fate of most women was to grow up and leave for another household which they were expected to run and where they were to produce and bring up children. The most influential book at the time on the role of women was The Greater Learning for Women with which Tsuneno would have been familiar. It describes the most important qualities for a woman as “gentle obedience, chastity, mercy and quietness” and the most important of the many skills a woman needed was needlework. Tsuneno was clearly not a model pupil.

Divorce, however, was not unusual as, marriages were arranged by the family, so it was accepted they would not always work. Indeed, almost half of first marriages seem to have ended in divorce. That said Tsuneno was exceptional in marrying four times. This was partly because she was unable to produce children and partly because she was so grumpy and ill-tempered. Indeed, when she married for a fourth time her elder brother, now head of the family, told her husband to be that “as you probably know, she’s a very selfish person, so please return her to us if things don’t go well.”

Divorce, however, was not unusual as, marriages were arranged by the family, so it was accepted they would not always work. Indeed, almost half of first marriages seem to have ended in divorce. That said Tsuneno was exceptional in marrying four times. This was partly because she was unable to produce children and partly because she was so grumpy and ill-tempered. Indeed, when she married for a fourth time her elder brother, now head of the family, told her husband to be that “as you probably know, she’s a very selfish person, so please return her to us if things don’t go well.”

For anyone interested in the culture and history of Japan, this is a rewarding and enjoyable read. It not only captures the character of Tsuneno and the city of Edo but also of family life in both town and country for those not part of the political and social elite. What stands out perhaps most of all is the strength of the bonds of family. However wilful and independent Tsuneno may have been, Professor Stanley is only able to tell her story because of the letters she wrote home throughout her life and the care with which they were preserved.

Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography 2020, ‘Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Woman’s Life in 19th Century Japan’ by Professor Amy Stanley is available now in hardback, published by Chatto & Windus. RRP £16.99. The paperback is published on 15th July 2021. For more information, please visit www.penguin.co.uk.