The reaction of some to yet another book on the Holocaust might be to groan quietly under their breath. Surely there are no more stories to tell and there is nothing new to be said. They would be wrong, not just because the Holocaust is a story that ought to be endlessly re-told as a terrible reminder of the evil of which we are capable, but also because new evidence and new stories continue to emerge. The Escape Artist by Jonathan Freedland is one of those stories. It is not a completely new story and will probably already be known by those who have read deeply about the Holocaust, but it has never been told in such searing detail before. It is the story of Rudolph Vrba, one of the two young men who not only managed to escape from Auschwitz, the first Jews ever to do so, but then also authored the most detailed report of the industrial scale murder machine that was Auschwitz to reach the wider world, a report that was instrumental in helping save the lives of tens of thousands of the Jewish community of Budapest.

The Escape Artist is essentially a biography of Rudolph Vrba, with the main focus on his survival in and escape from Auschwitz. His first escape attempt was in early 1942 when, aged seventeen, he tried to escape from his home country of Slovakia to get to England. He made it into Hungary only to be arrested, beaten up and dumped back over the Slovakian border lucky to be alive. He was found by Slovakian border guards and sent to Novaky, one of the forced labour camps in Slovakia. He then escaped from Novaky only to be recaptured and put on the next transport to Poland, to Madjanek, a forced labour camp that also operated as a vernichtungslager, extermination camp. He then volunteered for farm work. It was not to be quite what he expected as on the evening of 30th June 1942 he discovered he was now in Auschwitz.

The Escape Artist is essentially a biography of Rudolph Vrba, with the main focus on his survival in and escape from Auschwitz. His first escape attempt was in early 1942 when, aged seventeen, he tried to escape from his home country of Slovakia to get to England. He made it into Hungary only to be arrested, beaten up and dumped back over the Slovakian border lucky to be alive. He was found by Slovakian border guards and sent to Novaky, one of the forced labour camps in Slovakia. He then escaped from Novaky only to be recaptured and put on the next transport to Poland, to Madjanek, a forced labour camp that also operated as a vernichtungslager, extermination camp. He then volunteered for farm work. It was not to be quite what he expected as on the evening of 30th June 1942 he discovered he was now in Auschwitz.

Rudolph was not yet eighteen when he arrived at Auschwitz and nineteen and a half when he escaped in April 1944. During the intervening twenty-one months Rudolph somehow survived everything that was thrown at him. He never allowed himself to become one of the muselmanner, the derogatory concentration camp slang used to describe those who had become resigned to their fate and given up the will to live and those whose physical condition had become so bad they could no longer stand up straight. What Rudolph could not avoid was typhus and severe beatings. These he survived was a mixture of luck, strength of character, intelligence and the help of friends in the Jewish underground with access to the concentration camp marketplace for favours, food and medicines that those in the know could tap into.

Having survived typhus when most did not and having worked on the railway ramps where the train loads of victims were unloaded Rudolph dedicated himself to memorising every detail that he could. He not only memorised the layout of the camp and how it was run but also the endless trains full of new victims, how many there were and where they came from. He was helped by getting a job working in the mortuary for Alfred Wetzler, one of the registrars. They agreed to escape together to let the world know what was happening at Auschwitz. How they did so is a remarkable story.

The over thirty-page report created from their knowledge ended up both in Whitehall and Washington. To their great frustration it was not made public in Hungary even though the Germans were moving the Hungarian Jewish community to Auschwitz. This scarred Rudolph for life. For him it was the deception and secrecy with which the ‘Final Solution’ was carried out that explained the docility with which he had seen its victims behave. They did not know, and if they did, did not believe, what was going to happen to them. That said, pressure behind the scenes using the report did result in much of the Jewish community in Budapest surviving – the Nazis had left them till last.

Rudolph may have escaped from Auschwitz and built a new and fulfilling life for himself but for all that Jonathan Freedland describes him as an ‘escape artist’ the one escape Rudolph never made, that Jonathan Freedland admits, was from his deep-seated anger that his report was not used, as he believed it could have been, to help save even more. It was an anger that often damaged his relations with his own community and perhaps explains why he never really received the honour that was his due. He had spent so much energy while at Auschwitz in committing the appalling statistics of murder to memory, train load by train load, that those saved by his survival seemed an inadequate return.

Rudolph felt this so passionately because he believed that if they had known the truth they could have made the choice, as he put it, to be deer rather than sheep and deer are more difficult to catch. We will never know what would have happened especially as so many when faced with the awful truth would not allow themselves to believe it. Perhaps no one has put it better than Raymond Aron who said when asked about the Holocaust: ‘I knew, but I didn’t believe it. And because I didn’t believe it, I didn’t know.’ For those who might have known as they clambered aboard the cattle trucks with their frightened families it was perhaps easier not to believe and who are we to judge.

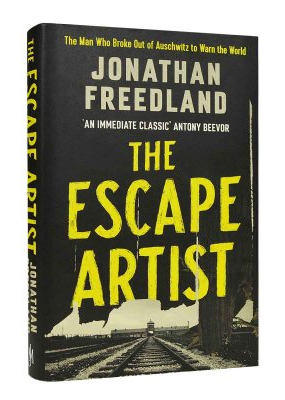

The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World by Jonathan Freedland is out now, published by John Murray Press.

Photos by Karsten Winegeart (courtesy of Unsplash)