The unprovoked Russian assault on Ukraine in pursuit of Putin’s vainglorious dream of reversing the collapse of the Soviet Empire has brought Ukraine to the centre of the international stage for the first time since the 1986 nuclear disaster at Chernobyl, when Ukraine was one of the constituent republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

There is, though, as you might expect, a long history behind the headlines. For anyone wishing to learn more about the complex history of Ukraine, its emergence as an independent state, the development of a Ukrainian national identity and the reasons why the Russians reject the existence of an independent Ukraine there is no better starting point than Professor Serhii Plokhy’s The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine which has recently been updated and re-issued.

Professor Plokhy is the current holder of the Hrushevsky Professorship of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, a professorship established in 1975 in honour of one of the leading lights of early 20th Century Ukrainian nationalism. Plokhy wears his learning lightly, writes with clarity and wit and is adept at using interesting, and often entertaining, anecdotes to illustrate his narrative. His aim in writing the book, as he makes clear in his introduction, is to help explain the historical background to, and roots of, the current conflict – a conflict, it is easy to forget, that first began in 2014 with Russian intervention in the Donbass and their annexation of Crimea. He certainly succeeds in meeting his aim. In doing so he illustrates what differentiates Ukrainians from Russians; the role played by the strategic and physical geography of Ukraine; and the impact of changing political borders on ethnicity and culture. It is a fascinating journey that starts with Herodotus and finishes with the current war.

Professor Plokhy is the current holder of the Hrushevsky Professorship of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, a professorship established in 1975 in honour of one of the leading lights of early 20th Century Ukrainian nationalism. Plokhy wears his learning lightly, writes with clarity and wit and is adept at using interesting, and often entertaining, anecdotes to illustrate his narrative. His aim in writing the book, as he makes clear in his introduction, is to help explain the historical background to, and roots of, the current conflict – a conflict, it is easy to forget, that first began in 2014 with Russian intervention in the Donbass and their annexation of Crimea. He certainly succeeds in meeting his aim. In doing so he illustrates what differentiates Ukrainians from Russians; the role played by the strategic and physical geography of Ukraine; and the impact of changing political borders on ethnicity and culture. It is a fascinating journey that starts with Herodotus and finishes with the current war.

The title of the book captures one of the Professor’s principal themes: that the area we know as Ukraine has long been a gateway between Europe and Central Asia, between East and West and how this helps to explain why it has so often been fought over, whether by the advancing Mongol horde, the rulers of the Lithuanian-Polish kingdom or the empire building of the Habsburgs, the Romanovs, the Bolsheviks and today of course, Putin’s efforts to re-establish the Soviet Empire built by the Bolsheviks. Prior to the current conflict the most recent and perhaps most extreme example of this is exemplified by the fate of Kyiv during the latter months of the First World War and the Russian-Polish and Russian Civil wars that followed. In less than three years the city changed hands at least 16 times as Germans, Poles, Ukrainian nationalists, Cossacks, White Russians and Bolsheviks took turns to rule it in pursuit of their different objectives. The nightmarish impact of this turbulence on the citizens of Kyiv provides the setting used by Mikhail Bulgakov for his novel ‘The White Guard’.

Still from ‘The White Guard’ (2012, Janson Media)

History is frequently a battleground of competing narratives as different sides seek to tell the story that best suits their beliefs. Much of the historical debate over the causes and nature of the French Revolution, for example, used to be coloured by an ideological clash between Marxist and non-Marxists. For a more recent example one only has to compare the Greek Cypriot version of the history of the division of Cyprus in 1974 with the Turkish Cypriot version. Those writing the history of Ukraine are often equally divided. In this case, the main division is between Russian and Ukrainian nationalists. An extreme version of the former can be found in Putin’s essay published in July 2021 with the title “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”. It is this essay which provides the ideological under-pinning for his assault on Ukraine. For Putin the collapse of the Soviet Union was, to use his own words “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” and there is no such thing as a separate history of Ukraine or a separate Ukrainian identity. There is only a story in which Ukraine and Ukrainians are inextricably bound to Russia and the Russian state.

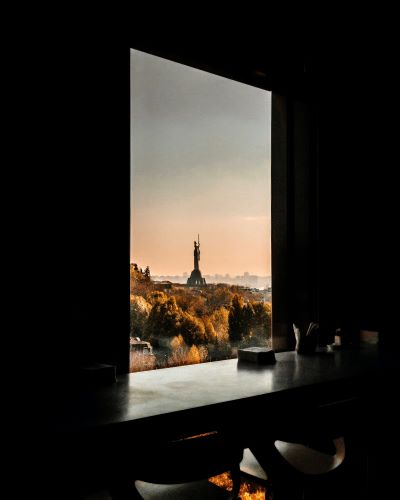

Kyiv (photo by Kyrylo Kholopkin, courtesy of Unsplash)

Professor Plokhy is clearly on the other side of the divide and writing a Ukrainian version of history. However, there is a major difference between his approach and that of Putin. Whereas Putin has written a polemic that is dismissive of the Ukrainian side of the story, Professor Plokhy acknowledges the complexity here and pays due regard to the many deep historical links that exist between Ukraine and Russia, whether political, familial, religious or cultural; in particular, he illustrates the many links that developed following the Russian conquest of Ukraine in the 18th Century as ambitious Ukrainians pursued careers in the service of the Russian state and Ukrainians and Russian families inter-married, a process that continued under the Soviets. However, as Professor Plokhy makes very clear, this never expunged the existence of a Ukrainian identity.

What emerges from the story Professor Plokhy tells is the complexity of the Ukrainian experience, a complexity that does not just involve Russia, and one which frequently involved attempts to carve out an independent Ukraine of some kind. This complexity is especially evident in the development of modern Ukrainian nationalism that began during the 19th Century. The rise of nationalist movements seeking escape from the dynastic political structure that still dominated much of Europe was a significant influence. Different versions of Ukrainian nationalism emerged in western and eastern Ukraine. The former was largely still part of the Austrian Empire while the latter was under Russian rule and the experience was very different. Last but not least there was the complication that some parts of both western and eastern Ukraine, Galicia and Little Russia as they were often called, were populated by Hungarians and Poles, both of whom also had nationalist dreams.

The short-lived Ukrainian state that emerged out of the post-war collapse of the Romanov and Habsburg Empires may have been overwhelmed by the Red Army, as the Bolsheviks built the Soviet Union out of the wreckage of the Romanov Empire, but the flame of Ukrainian nationalism was never extinguished. It may have gone underground but given the horrors inflicted on Ukraine by Stalin, not least the terror famine, the Holodomor, of 1932-33, it comes as no surprise to Professor Plokhy that Ukrainians sought independence from Russian rule as soon as they could when the Soviet Union started to collapse in 1991, just as did so many other parts of the Soviet Empire.

Photo by Rostislav Artov (courtesy of Unsplash)

It is still too early to predict the outcome of the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict with any certainty although, if the West remains fully committed to supporting Ukraine, it is clear Putin will not be able to fulfil his aim to take Ukraine back under the heel of Russia. What is already without doubt, is that the Russian so-called ‘special operation’ has almost certainly done more to strengthen Ukrainian national identity and the desire of Ukrainians to look west and be seen as Europeans than any other event in their history. Reading ‘The Gates of Europe’ will help explain why, despite Putin’s assertion that Russians and Ukrainians are one people and there is no such thing as a Ukrainian nation, the Ukrainians are fighting with such determination to defend their homeland. To paraphrase Mikhail Bulgakov, a Russian born in Kyiv, the Ukrainians, not for the first time, are “guarding the peace of their hearth and home, which if the truth be known, is the only cause for which anyone ought to fight.”

A New York Times bestseller, ‘The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine’ by Serhii Plokhy is out now, published by Basic Books.

Header photo by Robert Anasch on Unsplash