Many contemporary Arab authors find themselves confronting challenges similar to those faced by writers in 19th Century Russia. Writers such as Dostoyevsky, Herzen and Turgenev often wrote fiction to escape the censor and confront issues that could not be addressed openly. Even then this sometimes resulted in either enforced or self-imposed exile. When contemporary Arab authors use their fiction to address issues in a way that challenges political and religious norms, they frequently have to get their work published outside their own country and have to live abroad in what is, in effect, a form of exile. This has certainly proved to be the case for the Egyptian writer Alaa al Aswany, and for his most recent novel The Republic of False Truths, which has just been translated into English.

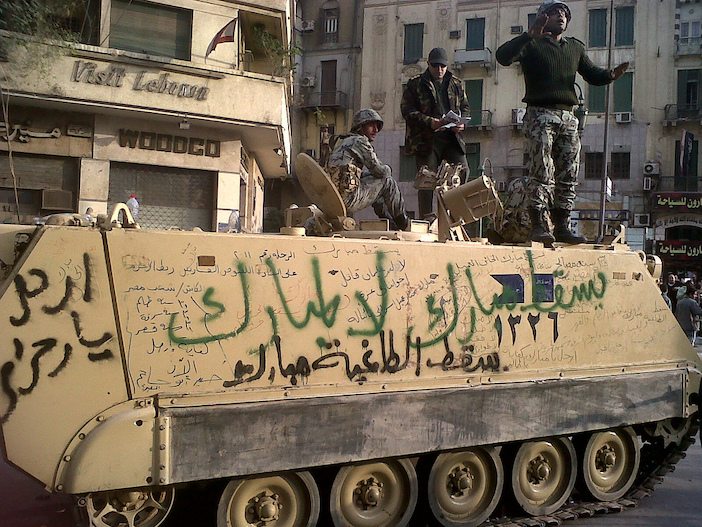

The Republic of False Truths is set round the 2011 Egyptian Revolution and, although fictional, is a savage excoriation of the military dictatorship; the brutality, corruption, illiberalism and religious hypocrisy that followed in its wake. Unsurprisingly, given its contents, it could not be published in Egypt and was printed in Lebanon. Aswany’s high-profile involvement in the events of 2011 – he was one of the founders of the Kefaya (Enough) movement that opposed the military dictatorship as early as 2004 and had humiliated Mubarak’s prime minister Ahmed Shafik on national TV in March 2011 – had already meant that he was no longer able to publish anything in Egypt once President el-Sisi and the military reclaimed power in 2013. It should come as no surprise that he now lives and works outside Egypt.

The Republic of False Truths is set round the 2011 Egyptian Revolution and, although fictional, is a savage excoriation of the military dictatorship; the brutality, corruption, illiberalism and religious hypocrisy that followed in its wake. Unsurprisingly, given its contents, it could not be published in Egypt and was printed in Lebanon. Aswany’s high-profile involvement in the events of 2011 – he was one of the founders of the Kefaya (Enough) movement that opposed the military dictatorship as early as 2004 and had humiliated Mubarak’s prime minister Ahmed Shafik on national TV in March 2011 – had already meant that he was no longer able to publish anything in Egypt once President el-Sisi and the military reclaimed power in 2013. It should come as no surprise that he now lives and works outside Egypt.

Aswany comes from a highly educated Egyptian family with political and aristocratic connections. He trained as a dentist in Cairo and then Chicago but always had a passion for literature and politics. In parallel with his dentistry he soon began writing articles for a range of Egyptian newspapers and magazines. He first came to prominence as a novelist, both in the Arab world and internationally, with the runaway success of his second novel The Yacoubian Building. Since its first publication in 2002 it has been turned into a successful film and translated into over 20 languages, making him probably the best-known Egyptian novelist of his generation. The book is set in the 1990s and looks at the complex lives of the varied inhabitants of a once luxurious but now decayed 1930s building in Cairo. It was a building Aswany knew well as he once ran his dental practice from it. The success of the book comes from the way he not only brings his characters and their individual foibles to life but also how he manages to use them, sympathetic or unsympathetic, as emblems of the good and bad – frequently the latter – in Egyptian society. Amidst all the corruption and cruelty he also has an unerring and satirical eye for the comic and capriciousness in human behaviour.

The Republic of False Truths brings with it the same virtues as its predecessor but with an extra edge that comes from the disappointment Aswany clearly still feels at the failure of the demonstrations in Tahrir Square to lead to the more open, liberal, democratic Egypt he wishes for his country. His sense of disappointment is accompanied by the deep anger he also feels at the violence he saw at first hand that was used to crush the movement; a young man he was talking to in the square was shot dead by a sniper a few minutes later.

The shadow of Tahrir Square hangs over the story that Aswany weaves as it provides a powerful backdrop against which his characters live out their lives. It brings them into contact with each other and drives their decisions as they are forced to choose sides in the struggle over the kind of Egypt that would emerge after the overthrow of the Mubarak military dictatorship. Was it to be a new liberal Egypt that opened the door to democracy and rights for women? Was it to be the Islamist state desired by the Muslim Brotherhood? Or was it to be yet another military dictatorship?

The military dictatorship is represented by General Alwany, head of the security service. We see him in the local mosque, then watching porn and then in his office supervising interrogations and torture. Later, he worries about his beloved daughter Danya, a medical student, who has fallen under the influence of Khaled, a dedicated political activist involved in opposition to the dictatorship. Those on the make and hanging onto the coat tails of the military are represented by Essam Shalaan a one-time political activist now cynical manager of a cement factory and by Nourhan his social climbing wife who exploits her seductiveness to become a mouthpiece on TV for the regime.

Meanwhile, Mazen Saqqa is the embodiment of youthful idealism. He is a young engineer and trade union representative in Shalaan’s factory while his girlfriend Asmaa Zanaty is a teacher and political activist. Mazen is exposed to the cynicism of Shalaan who tells him that the cause is hopeless because Egyptians are cowardly and submissive by nature and love dictatorial heroes. Hovering in the background is Ashraf Wissa, a middle-aged Coptic aristocrat in an unhappy and loveless marriage who lusts after the maid and finds solace in smoking hashish. As a member of the Coptic minority he has always kept a low profile but because he has a house near Tahrir Square he finds himself becoming increasingly involved in events.

Aswany uses excerpts from the statements of actual witnesses and victims of the violence that was used against anyone getting in the way of the reimposition of military control or often, just because they could. These testimonies and especially those from the point of view of violated women add to the verisimilitude of the story like old film reels cut into a modern film.

Aswany’s writing is stylish and full of descriptive nuance; the tale he tells about his country is illuminating and, as ever, there is a colourful cast of characters. Some might argue that he occasionally comes close to turning one or two of his characters into stereotypes, most especially in the case of General Alwany. Personally, I suspect that Aswany’s intention was to hold the dictatorship to account by creating a satirical figure. Regardless of this, The Republic of False Truths is certainly well worth reading even if in the end one is left wondering how Egypt, let alone many other countries of the Arab world, will ever manage to escape from the competing totalitarian challenges often presented by their militaries and by the fanatical adherents of fundamentalist religion. What is certainly the case, as Aswany’s novel makes clear, is that opposition to tyranny of whatever kind always comes at a cost, especially to those brave enough to put their heads above the parapet.

The Republic of False Truths by Alaa al Aswany is published by Faber, available in hardback, priced £16.99. For more information, including details about the author, please visit www.faber.co.uk.

Photos courtesy of Creative Commons