David Grann’s latest book The Wager, A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder tells the story of the disastrous voyage of the 28-gun frigate The Wager across the Atlantic and round Cape Horn as part of a Royal Navy flotilla to attack Spanish shipping in the Pacific during the War of Jenkin’s Ear. It is a dramatic change from his previous book Killers of the Flower Moon, set in the rolling hills and open prairie of Osage County that runs north from Tulsa, Oklahoma and dealing with the murders of members of the Osage tribe in the 1920s over the rights to the oil that was discovered on their tribal lands.

The story of The Wager is far more death ridden: a combination of scurvy (the most lethal killer of those at sea until late in the 18th Century), typhus, starvation, and the power of the sea, all made worse by the bitter divisions that increasingly developed between the survivors. The world of The Wager is also far more claustrophobic than that of Osage County. It is peopled by a crew of some 250 when the voyage begins and, until it was shipwrecked, they were all cramped together behind its wooden walls, a vessel some 120 feet from bow to stern, 30 feet across the beam and 14 feet from the gun deck to the keel.

The story of The Wager is far more death ridden: a combination of scurvy (the most lethal killer of those at sea until late in the 18th Century), typhus, starvation, and the power of the sea, all made worse by the bitter divisions that increasingly developed between the survivors. The world of The Wager is also far more claustrophobic than that of Osage County. It is peopled by a crew of some 250 when the voyage begins and, until it was shipwrecked, they were all cramped together behind its wooden walls, a vessel some 120 feet from bow to stern, 30 feet across the beam and 14 feet from the gun deck to the keel.

Grann successfully uses his comprehensive and detailed research to recreate the increasingly antagonistic and ill-disciplined atmosphere that develops amongst the survivors of the shipwreck of The Wager and eventually results in a mutiny. He does not allow his bleak but colourful story to become drowned by the depth of his research. Instead, he uses telling details to illustrate the full horrors of the voyage, the tough and frequently unforgiving nature of the 18th Century Royal Navy and the very different characters and background of the two principal protagonists that come to dominate his story. This is no romantic Mutiny on the Bounty in which the majority of both mutineers and non-mutineers survive.

Grann also provides an excellent overview of the background to the voyage undertaken by The Wager and of the conflict between England and Spain that precipitated it. The War of Jenkins Ear, so-called because a British merchant ship captain was alleged to have had an ear severed by Spanish coastguards when searching his ship, was mostly conducted in the Caribbean. The flotilla of which The Wager was part was under the command of Commodore Anson, later to become First Lord of the Admiralty. It was composed of six warships and two store ships. Its task was to disrupt Spanish trade in the Pacific and capture one of their treasure ships. Anson succeeded in these tasks and his return to England via the Cape of Good Hope saw him complete a circumnavigation of the world.

The expedition lasted nearly four years and made Anson’s reputation even though it was completed at great cost in ships and men. By the time the flotilla had rounded Cape Horn it was reduced to three ships with much reduced crews. One of the merchant ships had turned for home before reaching Cape Horn, the other survived but was in such a state that it was abandoned, and its crew transferred to the three remaining warships. Two of the other warships never made it round Cape Horn and eventually returned home via the east coast of South America and another Atlantic crossing. The Wager, the last of the six warships, made it round Cape Horn only to become shipwrecked on the coast of the northern tip of what are now the Chilean fjords. As for the human cost, less than 500 of the 1900 who set sail in the autumn of 1740 survived.

The expedition lasted nearly four years and made Anson’s reputation even though it was completed at great cost in ships and men. By the time the flotilla had rounded Cape Horn it was reduced to three ships with much reduced crews. One of the merchant ships had turned for home before reaching Cape Horn, the other survived but was in such a state that it was abandoned, and its crew transferred to the three remaining warships. Two of the other warships never made it round Cape Horn and eventually returned home via the east coast of South America and another Atlantic crossing. The Wager, the last of the six warships, made it round Cape Horn only to become shipwrecked on the coast of the northern tip of what are now the Chilean fjords. As for the human cost, less than 500 of the 1900 who set sail in the autumn of 1740 survived.

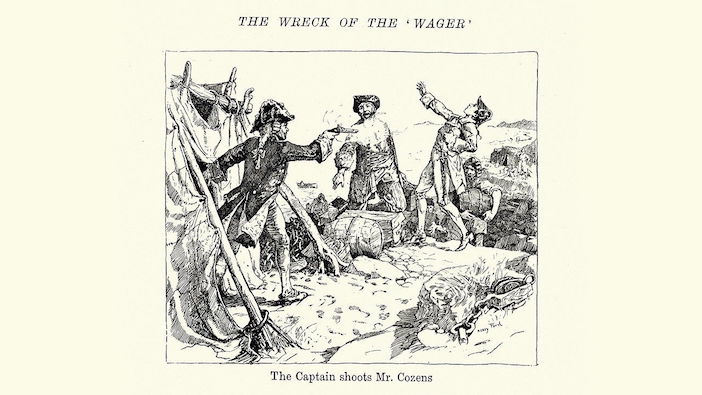

At the heart of Grann’s story is the fate of The Wager and its crew. It is a story dominated by the personal conflict that developed between the inexperienced and dictatorial Captain David Cheap, who had only been promoted to command The Wager during the voyage, and the experienced gunnery officer John Bulkeley. Their conflict became open and resulted in mutiny only after The Wager had been shipwrecked and the 145 survivors of the 250 who had set out from England were struggling to stay alive. Matters came to a head after Cheap shot dead Midshipman Cozens in a fit of rage. Bulkeley then set off with 81 of the survivors in two of the ship’s boats leaving Cheap with the remaining 20 still alive. Grann relates in grim detail the battles for survival first from the shipwreck and then how the two parties struggle to get home: their failure to keep on friendly terms with the indigenous population, their struggles to find food, their exposure to wind and water as they sailed in The Wager’s small boats, and their unfriendly treatment at the hands of the Spanish and, on occasion, the Portuguese.

Scurvy, the result of a lack of vitamin C, is the real killer in Grann’s story. By the time Anson’s flotilla had crossed the Atlantic and sailed down the eastern seaboard of South America to Cape Horn almost half of his seamen had succumbed to it. In the case of The Wager almost half the original crew had been struck down by scurvy when the shipwreck occurred. Scurvy, incidentally, remained the principal killer of Royal Navy seamen until the carrying of lemon juice and sugar was made mandatory on all ships in 1795.

Vintage engraving showing a scene from Wreck of HMS Wager and the subsequent marooning and mutiny that followed.

Grann ends his story with a court martial. This was standard practice when a ship was lost or seriously damaged. Cheap had to explain and justify how he lost The Wager. And then there was the charge of mutiny brought by Cheap against Bulkeley. What made both issues complicated was the two-year gap between the return of Bulkeley and his small party and the unexpected arrival of Cheap and his three companions, one of whom, Midshipman Byron, later became both an Admiral and the grandfather of the poet Lord Byron. Once home, Bulkeley had made use of a publisher to tell his story and it sold well given the appetite for sea stories created by Daniel Defoe using the adventures of Alexander Selkirk. The tales of both groups of survivors captured the public imagination and placed the Admiralty in a quandary. Grann uses the court martial to provide a fascinating and unexpected ending to his story.

Aficionados of Patrick O’Brian and C. S. Forester will enjoy this well-written and well-constructed book as will anyone interested in 18th Century seamanship, and the Royal Navy in particular. Grann illustrates the vulnerability of ships and their crews to the dangers of the mighty oceans, the tough life of a seaman and how quickly the claustrophobic world of an 18th Century ship could unravel and deteriorate when leadership was either weak or over-dictatorial and uncaring. Not every ship was lucky enough to be captained by a Horatio Nelson or an Edward Pellew, let alone by a fictional Horatio Hornblower or Jack Aubrey. However, without enough of their ilk, it is unlikely the 18th Century Royal Navy would have suffered so few mutinies let alone been so successful. That said, there is no getting away from the harsh reality. In the 11 years of war with Napoleonic France between 1804–1815, the Royal Navy suffered nearly 92,300 casualties. Of these only some 6600 were killed in action and another 13,600 died from shipwrecks, drowning or fire. A massive majority, some 72,100, died from disease and injury, and by far the largest number of these from disease of one kind or another.

‘The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder’ by David Grann is out now in hardback, published by Doubleday, priced £20 and available from Hatchards, and all good stockists.