In the first of a new series of reviews and discourses on film and television, filmmaker, photographer and artist, Paul Joyce, reviews This England on Sky Atlantic…

Genius is a term usually applied to classically top-end professions, artists, composers, scientists, authors, inventors, rarely to the lowlier occupations such as film and television. Who would you push forward, for example, as a wunderkind of television? John Logie Baird maybe, but there we return to the realms of pure invention. I am talking creative abilities here, and in pure televisual terms, it is perhaps easier to think of great programmes rather than the individual creative force behind them: The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, The Wire, Succession, Twin Peaks, Friends, Star Trek, Downton Abbey, The Crown, Dr Who (one four-parter from the 80s I am proud to have co-wrote and directed) etc. But Vince Gilligan and Jesse Armstrong are by no means household names, whereas perhaps Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg are?

My point is that TV has long been the poor relation in the media stakes, but undeservedly so. The problem is that its popularity demeans it in the eyes of the cultural establishment, but it is surely a medium that Shakespeare and Dickens would have embraced wholeheartedly. For me absolutely game-changing shows were Jeremy Isaacs’ The World at War, the original Civilisation with Kenneth Clarke, Planet Earth and in the field of so called docu-drama, in recent years Chenobyl was a total revelation in terms of acting, historical recreation and sheer dramatic imperative. I have no idea who was the “genius” behind that, but for me this is one of really few occasions when that epithet can be liberally applied.

I come to This England not so much as an unbiased viewer but as a director both of dramas (Play for Today, Film on Four) and over 40 arts documentaries, and I feel impelled to write this piece and correct what I think are mistaken, churlish and in some cases downright aggressive reviews of the series thus far.

“It is hampered from the off by feeling both too soon and wildly out of date. The entire project now has the air of only telling half the story and not telling the truth. The characters are merely ciphers, even Johnson. Johnson is nothing more than the idle, cowardly buffoon we already know him to be. Cummings is no more than the robotic weirdo whose image you conjure from the times when he was still allowed to appear in front of cameras. Care home supervisors and members of the public whose sickening, ventilation and deaths we see are merely sketched in. This is a disservice.” The Guardian

“Sky’s Covid drama should be avoided like the plague. Anyone who endures the full run of six hour-long episodes deserves the nation clapping them in their driveways. And “endures” is the word for it. The rendering of the miserable past two years as a form of entertainment was an inexplicable decision, and the botched execution is simply a by-product of that central commissioning error.” The Independent

“Branagh’s Boris Johnson is buffoonish and endlessly distracted by his personal life, but the drama avoids a hatchet job. It doesn’t really delve beyond the Johnson caricature or attempt to apportion blame.” BT.com

It is quite astonishing to think that a major six-part series was written, cast and shot before Boris’s successor was even sworn in. The speed of change not only in this respect, but the way that even the living can be portrayed with impunity and, apparently, freedom from prosecution. Not so long ago, journalists and commentators quaked in their shoes at the prospect of being sued by one Robert Maxwell, who was litigious to a fearsome degree. Indeed, even when David Suchet played him years after his demise, the ending of how or why he was, at least in the opinion of many, tossed off his yacht was fudged and bypassed.

If that were to be made today, the death could be resolved dramatically by focusing on a disenfranchised deck hand, bitter pension fund investor, former business partner (Rupert Murdoch?). I remember Helen Mirren telling me that she had no idea, when being approached to play the Queen, that such a thing was even possible. Fortunately, in my experience, this licence to deal directly with recent events has not on the whole been abused (ie. The Crown). And with This England I for one would like, in my humble opinion, to set the record at least a bit straighter than the tabloids would have us believe.

The format of This England is that of, for want of a better phrase, docu-drama (a term I hate, incidentally). In dramatic terms, either a show is drama, or it is a documentary and all the best dramas combine both to varying degrees, and thus have a documentary feel to them – just think of Citizen Kane in that context for a moment. So the writer and director, Michael Winterbottom (The Killer Inside Me; The Trip(s) with Rob Bryden and Steve Coogan, Welcome to Sarajevo) has crafted an extremely fast-paced pot-pourri of materials culled from multiple sources and references to the point that is frequently impossible to tell real from recreation.

The editing speed is also an integral element of the series, as Covid was overtaking events on a pretty much daily basis in precisely the same manner. Here form and content lock in a remarkable and immensely satisfying way. As someone, indeed like most of us, who lived through those two plus years of anxiety and lockdown, it seemed that the government was engaged (or not, mainly) in a series of disastrous cock-ups, but in This England this does not seem to be the case. Rather arguments are put forward, sometimes heatedly and frequently very sensibly, by people who in the main bear a sense of responsibility and moral accountability. If tens of thousands died needlessly it was through inaction and indecision at the highest levels of the state, ending with Boris as the most culpable in this respect. Indecision spills blood onto the carpet.

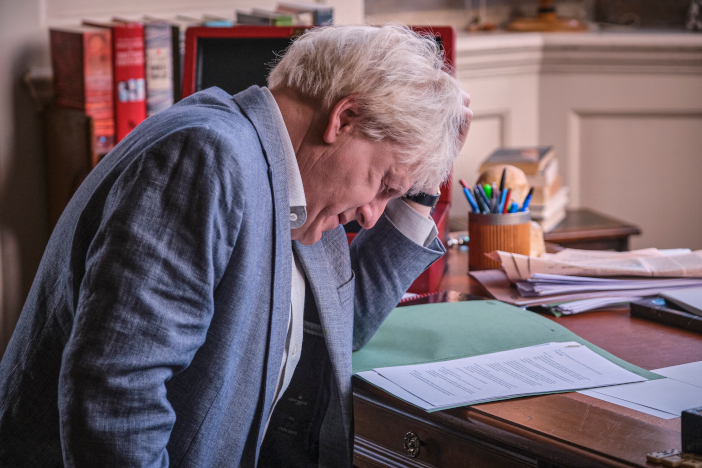

Much talk has been made of Kenneth Branagh’s prosthetics which frankly bothered me not at all. It seemed to me to be a magical transformation his team had achieved, and added to the fact is that Boris looks like a man born with prosthetics as a genetic inheritance anyway! Branagh clearly studied the man very carefully and has captured the walk, arm waving, verbose stumblings and mumblings, hair and bollock scratching, to a tee. This is not a caricature (how can you caricature a caricature?) but a fully rounded portrait of a man of a thousand words, but with little to say. Branagh is one of our greatest acting talents and a true inheritor of Olivier’s (a personage he has played on more than one occasion).

From Henry V to Wallander he has shown flashes of quiet and frequently unspoken genius (yes, I will return on that word again later) and here he does not disappoint, inhabiting the role, room, building even in a way that we are led to believe Boris himself is capable of doing. From relatively early on Branagh realises that he is playing a man who is actually impersonating a prime minister rather than actually believing he has a real role to fill. This means he is incapable of abandoning his ridiculous “hail fellow well met” bonhomie which surrounds him like impenetrable armour. He bounces in and out of meetings which clearly bore him rigid, as if a mere wave from the Emperor would calm stormy seas. This febrile atmosphere in No 10 is meat and drink to Boris, for it allows infighting and mutual suspicions to grow whilst he keeps a weather eye on friends and foes alike.

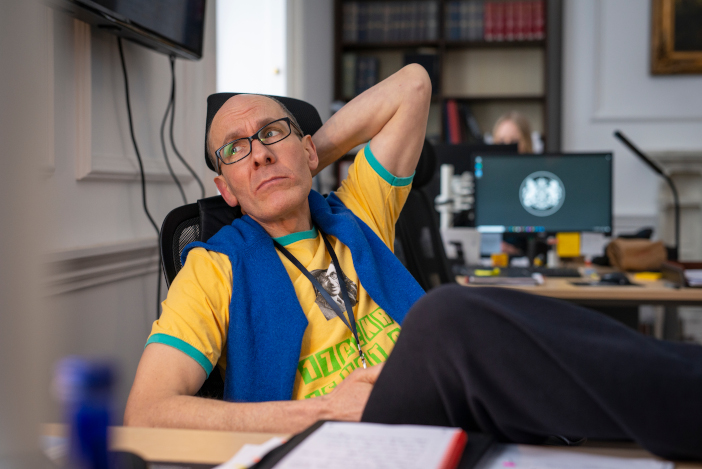

This is by no means a one-man show. Terrific actors step up to the plate (as they did in The Crown) with Simon Paisley-Day as the knuckle-skulled advisor with unfortunate memory lapses, Dominic Cummings. If criticism were to be directed here, it would be to the fact that the Machiavellian aspect of Cummings, which we all pretty much embrace as the truth, dissipates as the drama progresses; whereas my feeling is that his influence increased to the point that Boris saw him as presenting a challenge in terms of ideas and leadership within No 10. This may play out more dramatically than I suspect, but I am only two parts in to the series at present and much is yet to come.

Andrew Buchan is a dead-ringer for Hancock and brilliant to boot, and Ophelia Lovibond as Boris’s fiancée (later of course, wife) is all feet-on-the-ground good sense and practicality in the face of Johnson’s constant fanciful quotes from Shakespeare and The Histories.

All in all, this is riveting stuff as we watch our last three years flash by, without – until the final credits roll past – it seems any room at all for pause for breath or proper reflection of any kind. Oh yes, before I forget, what of the media geniuses I alluded to earlier? Are there any in the dog eat dog landscape of binge TV? Well maybe but they will have to up the ante to two series to begin to make a mark on the industry’s topographical map. In cinematic terms, Stanley Kubrick stands above Stephen Spielberg, as does Orson Welles over Oliver Stone. But then a considerable talent like David Fincher crosses and recrosses the almost invisible line now drawn between film and TV. Michael Winterbottom strikes me as a similar creature, moving from continent to ocean, then back again. In terms of raw, unapologetic, muscular, energetic, dramatic, informative and eye arresting stuff, This England has to be one of the year’s great series.

This England is currently streaming on Sky Atlantic and NowTV. Paul Joyce is a renowned filmmaker, photographer and artist. To contact the author, or to learn more about his work, visit his website or email him at pj.lucida@gmail.com.