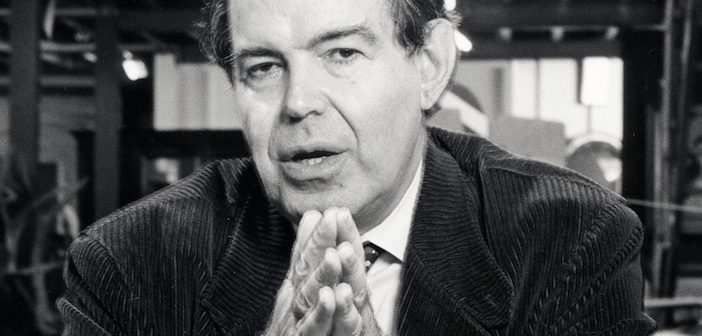

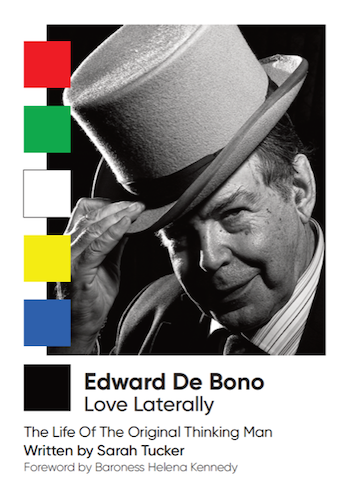

Ahead of the publication of a new biography, Sarah Tucker, reflects on the life of Edward de Bono, one of the world’s greatest contemporary thinkers, who died last week at the age of 88…

Edward Charles Francis Publius de Bono, was a Maltese physician, psychologist, visionary, inventor, philosopher and Nobel Prize nominee, although when I asked him last year how he would like to be remembered, he simply replied ‘author’, and, as his name suggests, ‘for doing good’.

The ultimate polymath, with an unrelenting probing intelligence, unquenchable curiosity, and boundless inventive imagination, his carpe diem attitude to life meant, when compiling his bibliography for his biography, Love Laterally, to be published later this year, there was ample sufficiency to give his prolific list of achievements a chapter of its own.

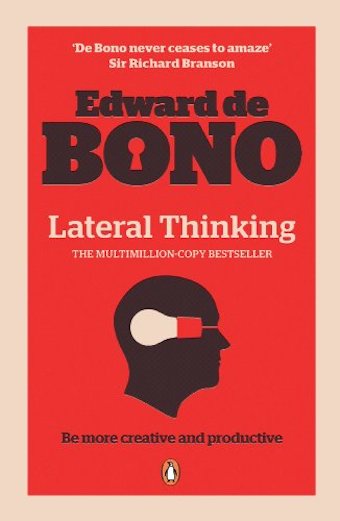

But he is possibly – probably – most celebrated for introducing the world to the concept of ‘lateral thinking’ which, in his 1967 title ‘The Use of Lateral Thinking’ he defined as a means of escaping established ideas and perceptions in order to find new ones. It became a best-seller, and his subsequent work (over seventy books translated into 36 languages), including the concept of parallel thinking, ‘Six Thinking Hats’ methods with schools, corporations, governments and world leaders, established him as the father of lateral thinking. I once asked Edward why he chose the number six and he replied, ‘it is a good number to remember.’

But he is possibly – probably – most celebrated for introducing the world to the concept of ‘lateral thinking’ which, in his 1967 title ‘The Use of Lateral Thinking’ he defined as a means of escaping established ideas and perceptions in order to find new ones. It became a best-seller, and his subsequent work (over seventy books translated into 36 languages), including the concept of parallel thinking, ‘Six Thinking Hats’ methods with schools, corporations, governments and world leaders, established him as the father of lateral thinking. I once asked Edward why he chose the number six and he replied, ‘it is a good number to remember.’

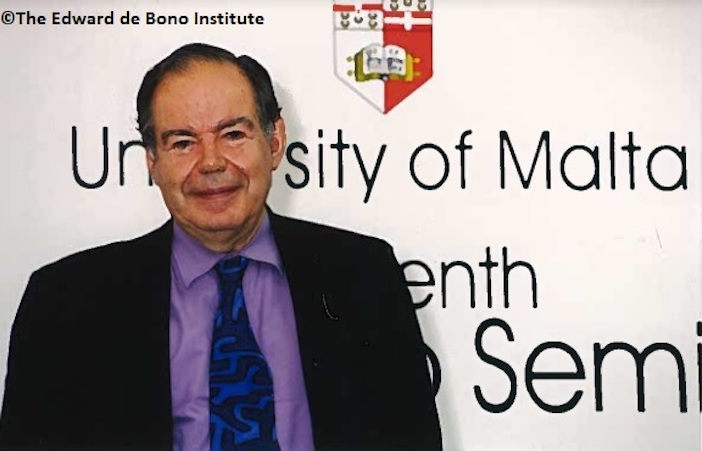

De Bono was a genius (indeed, it was his nickname at school in Malta), born to a country where necessity was the mother of invention, and to a family where the importance of education, fulfilling potential and serving others before yourself was instilled from an early age. His mother, Josephine Burns, was a journalist, Irish born, a suffragette who was instrumental in getting Agatha Barbara the first female minister and President of Malta elected in 1947, but never entered politics herself. She married Joseph de Bono, a Maltese doctor, who was highly revered on the island through his commitment to the Maltese people, even during times when there were strikes and war, he continued to serve the community.

Edward started as an undergraduate at Malta University at the age of fifteen, having been offered the Rhodes scholarship at Oxford at the age of nineteen, but was only able to accept it two years later in 1955. He completed his BA in two years before taking up a role as a research assistant in the Department of the Regius Professor of Medicine while studying for a DPhil in Medicine, as well as working as a junior lecturer in medicine at Oxford.

Although his academic achievements were considerable, it is evident from reading his books and listening to his presentations, he was frustrated with the way children and graduates were taught what to think rather than how to think. “Universities,” he once told me, “should be a portal through which students emerge with transcendent and transcended thinking rather than an archway through which they are funnelled in order to perpetuate narrow-minded perspective.”

Despite his frustration with the way in which students were taught (not) to think at university, he appeared to have enjoyed his university years immensely, actively taking part in sports and mixing in the highest of circles, playing polo with Lord Mountbatten, who later asked him to give a seminar to his admirals in Portsmouth and lecture the Atlantic colleges in Wales and Singapore.

He excelled in sport, particularly cricket, rowing and polo, through which he met HRH Prince Phillip at the Sandringham Polo Club. It was a friendship that he maintained until the death of the Duke earlier this year. “Sport challenged him, and when it no longer challenged him, he challenged himself,” Josephine, his ex-wife, told me when I met her. “The Oxford to London canoe trip he led while there, was a dare, but he accepted it, navigating thirty-three locks and beating the previous record by four hours. A challenge which later cost the lives of two men, who tried to better Edward’s feat.”

During his lifetime, de Bono lectured at Oxford, Cambridge, and as a Research Associate at Harvard Medical School, and as honorary registrar at the St Thomas Hospital Medical School within the University of London, and spoke to business conferences of thousands. But it was the informal discussions around his table at his London home opposite Fortnum & Mason in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, where he felt most at ease and appeared to enjoy the most. Known as ‘Albany Suppers’, he always invited an eclectic selection of people (princes and politicians, academics, musicians and actors) to discuss issues – usually six – a number that would comfortably sit around his table amid a mass of books piled high.

He was nominated for a Nobel Prize for his work to business and commerce in 2005, but never received formal recognition from the UK government despite being asked for advice on many occasions about educational and peace-keeping initiatives, including the Irish and Arab-Israeli conflicts, the latter of which he famously recommended Marmite being added to the diet as zinc constituted a large part of spread; a mineral which strengthens the immune system, and helps with anger management. Although the media at the time rather mocked his suggestion, it was typical of his non-linear thinking, but which in later years proved to be prophetic in his understanding of the importance of nutrition in maintaining good mental as well as physical health. ‘If the GP of today does not become the nutritionist of tomorrow, the nutritionist of today will become the GP of tomorrow,’ he told me.

Before it became on trend, he was well aware of the connection between mental well-being and the value of learning how to think, illustrated in his more philosophical works; The Happiness Purpose (1977), where he suggests a religion based on respect and positivity rather than love would cause less global conflict, and became more playful in his work in Why I Want to Be King of Australia (1999), which he wrote on a plane from London to Auckland, giving reasons as to how a leader should be chosen, the qualities they needed to possess, and why he would make an excellent monarch to a country which he openly admitted he felt most at home. He even noted throughout the book where he was flying at the time of writing. He told me he was immensely proud of being able to sing in the Sydney Opera House, when he headlined talks on creativity there in 2008, although he admitted, ‘I wasn’t particularly good.’

Before it became on trend, he was well aware of the connection between mental well-being and the value of learning how to think, illustrated in his more philosophical works; The Happiness Purpose (1977), where he suggests a religion based on respect and positivity rather than love would cause less global conflict, and became more playful in his work in Why I Want to Be King of Australia (1999), which he wrote on a plane from London to Auckland, giving reasons as to how a leader should be chosen, the qualities they needed to possess, and why he would make an excellent monarch to a country which he openly admitted he felt most at home. He even noted throughout the book where he was flying at the time of writing. He told me he was immensely proud of being able to sing in the Sydney Opera House, when he headlined talks on creativity there in 2008, although he admitted, ‘I wasn’t particularly good.’

It is a testament to his kindness and generosity of spirit that those I interviewed spoke of him with genuine affection as well as palpable respect. From the late HRH Prince Phillip to musician Peter Gabriel, to Baroness Helena Kennedy, who wrote the introduction to his biography, Edward’s influence structured their thinking and attitude towards thinking. His magnetic and creative communication skills enabled him to reach and enthuse the five-year-old school child as much as the hard-bitten CEO, and completely changed their mind set when they listened to him speak. Advertising gurus Dave Trott and Rory Sutherland, spoke of his magnetism and how instead of organising a client jolly one year, Trott asked De Bono to speak to his employees, leading to the advertising agency, according to Trott, “winning every advertising award going”.

He was invited to speak and/or represent his country at many events around the world, even sometimes being invited twice by accident. On one such occasion, he attended the Royal summer garden party a second time (although you are only supposed to attend it once). Josephine, his ex-wife, who was with him at the time, commented ‘the Queen noticed we were there and said ‘What are you doing here again? You are only supposed to be invited once.’ Edward explained what had happened – (the Maltese government had extended the invitation) and the late HRH Prince Phillip asked Edward how he was getting on with his work on lateral thinking. When the Queen asked what it was about, Phillip replied, ‘It’s something you do lying down.’

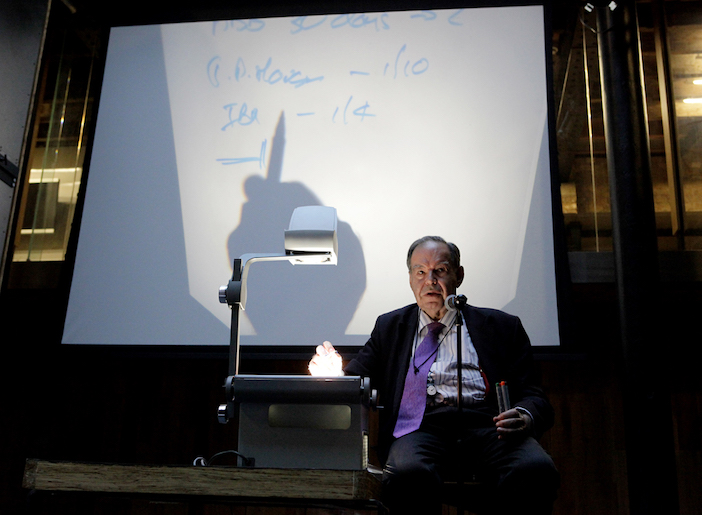

The use of humour was an intrinsic part of Edward’s presentations, of which he held thousands during his life, introducing jokes to explain how lateral thinking works and why it is relevant to the everyday rather than as an add-on to keep the audience amused. He was able to hold an audience’s attention with ease, without fuss, just him on the stage, like an Ed Sheeran who needed nothing more than his roller board and laminated paper on which he would write. ‘Regardless of where he was in the world, and to whom he was speaking,’ his assistant Justine Gaspar told me, ‘the audience would want him to like them.’

The use of humour was an intrinsic part of Edward’s presentations, of which he held thousands during his life, introducing jokes to explain how lateral thinking works and why it is relevant to the everyday rather than as an add-on to keep the audience amused. He was able to hold an audience’s attention with ease, without fuss, just him on the stage, like an Ed Sheeran who needed nothing more than his roller board and laminated paper on which he would write. ‘Regardless of where he was in the world, and to whom he was speaking,’ his assistant Justine Gaspar told me, ‘the audience would want him to like them.’

Baroness Helena Kennedy, who has the first word in Edward’s biography I will leave with the last, “Most of my work has been around terrorism, domestic violence, and sexual violence. The psychiatrists with whom I worked on torture cases were able to read across to identify similar symptoms of PTSD in serious domestic violence cases. This sort of read-across saves lives. I was taking something from one place, one area of experience, and seeing if it can apply in another. I think lateral thinking is fundamental to human development, giving expression to creativity. Most breakthroughs in science and medicine and other fields like law happen by doing this. But Edward de Bono is more than that; he teaches people to think for themselves. Perhaps his legacy is yet to be realised.”

Love Laterally: The Life of the Original Thinking Man is published in September.

Sarah has also launched the campaign “Posthumous honours for Dr Edward de Bono”. You can read more and sign the petition here: http://chng.it/sfVNdvgB