Following his treatise on over-priced veg published in these pages to mark his debut novel, for his second novel, Books, we have another short story from Charlie Hill, pushing limits both for subject matter and for the reader. The clue’s in the title, this is not for the squeamish…

The pain in my gut was excruciating, the worse I’d had since my ear poured white pus. I put it down to some ropey tofu from the day before and tried to sit it out. It got worse. So I called an ambulance.

I was told I needed emergency surgery. I was sanguine about this. I am a modern man. A little bit anarchistic maybe and no lover of Big Pharma, but Hopi Indian treatments weren’t going to fix my lower intestine. Besides. At the time, I couldn’t have known that being in hospital would be such a ride.

It began with drugs and disorientation. Delirium. For the first three or four days after the operation, cathetered and prone in a writhing pit of bleeping drips, the madness was strong. On my first or second night on the ward, my six-year-old son tormented me by talking from the floor beside my bed, his voice as clear as it was unintelligible.

After I complained of being thirsty, my wife brought me a two litre bottle of fizzy water.

‘He can’t have that,’ said a nurse or doctor, ‘his stomach is distended. He’s nil by mouth.’ And then to me: ‘Your intestines are not working.

My wife took the bottle from me, put it in the cupboard by the bed. As she left, I retrieved it, flicking her some morphine-leery V’s. That night I drank the gassy lot.

Early the next morning, or the one after that, hooked up to saline, antibiotics and painkillers, I woke in a panic and tore out the thick plastic tube that went through my nose and into my stomach. It was there to drain the backed-up contents of my dead guts and I began to vomit immediately, farmyard gushes of lurid green semi-fecal matter.

I was moved into my own room. There I sucked on too much oxygen. As I waited, day after day, for porters to wheel me to radiation-heavy departments under the ground, the tap over the sink morphed into an unlikely Christ on the cross. Once, passing through wards on my way to the basement, snippets of conversation ended abruptly with lines from The Velvet Underground: ‘I’m on a late tomorrow and then saw animals at the zoo’; ‘Do you know where I can find the key to all tomorrow’s parties?’; ‘BP 143 over the classical music there, Jim’.

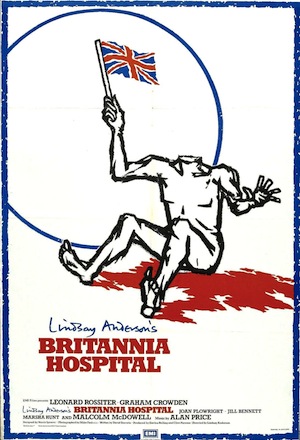

After about a week, the hallucinations stopped. I began to focus and was able to experience my surroundings through only the usual distortions. I was in a super hospital. Nearly ten floors of utilitarian promise, with a visitor flow system designed to reduce the spread of infection and no pictures on the walls. Nurses were from Ghana, Jamaica, the Philippines and Oldbury. There were three or four teams of doctors, consultants from Malaysia and  Greece. My notes were already copious. After the fizzy water incident, someone had written ‘Patient Non Compliant’; my removal of the Nasal-Gastro tube had brought the same response. A whiteboard behind my bed outlined what I was allowed to eat and drink. In the corridor outside my room, someone said: ‘I’ve spoken to pharmacy and your department needs to look at the way it manages its resources. You need a re-educating session. Can you do Tuesday, 3.30?’ On my drug stand, two pumps, one old, one new. The new one kept bleeping in the night, the old one was an IVAC Model 598, a stone cold design classic. Out of the window, a clash of space age architecture and old hospital buildings from the Space Age; in the middle of it all, a university rugby pitch, shaded by old trees.

Greece. My notes were already copious. After the fizzy water incident, someone had written ‘Patient Non Compliant’; my removal of the Nasal-Gastro tube had brought the same response. A whiteboard behind my bed outlined what I was allowed to eat and drink. In the corridor outside my room, someone said: ‘I’ve spoken to pharmacy and your department needs to look at the way it manages its resources. You need a re-educating session. Can you do Tuesday, 3.30?’ On my drug stand, two pumps, one old, one new. The new one kept bleeping in the night, the old one was an IVAC Model 598, a stone cold design classic. Out of the window, a clash of space age architecture and old hospital buildings from the Space Age; in the middle of it all, a university rugby pitch, shaded by old trees.

With the return of my critical faculties came renewed discomfort. I’d lost over a stone and was being fed mush, into a vein, to provide me with the nutrients I couldn’t digest. My stomach was hard and full and grotesquely distended. Green was still the colour. Yet the source of my disquiet wasn’t physical. I knew I was sick, but I wasn’t dying, at least not quickly, which was good enough for me. Instead, the soundtrack to my fretful nights and tottering drug stand waltzes comprised questions of agency, authority, control.

One morning a team of doctors flapped in, told me I needed a trace, flapped out. That afternoon, a second lot – hale Med School jocks – and an overrule: ‘That test is for IBS. He hasn’t got IBS’; now I needed a scan for a ‘something that might be growing’ on my liver. Then a third group – the consultant working wooden clogs – unclear about everything except the confusion. With each new visit, the whiteboard changed from ‘nil by mouth’ to ‘sips’ and back again.

Things were being done to me. Drugs prescribed and bloods taken and radiation administered by people who couldn’t agree on what was wrong with my body. And I had no say in any of it. I was helpless, being kept informed by best-guessers. I needed to somehow move attention away from inexact science, to put myself at the centre of the process. To aver my existence as a sentient being, make myself heard or known. But how? The answer came to me half by chance.

In the days following the operation, my body – unable to absorb liquid – had been drying out. Two weeks on and I was desiccated. My skin was peeling from my arms and feet. The whites of my eyes were bloody. I had no saliva, my tongue felt like towelling. ‘How are you today?’ the nurses would ask and I couldn’t reply. And so I started drinking water. Lots of it. Finishing jugs and asking for more.

Doctors came. Nodded at the message on the whiteboard. Eyebrows were raised and polite enquiries made. ‘How much water would you say you’ve drunk in the last two hours?’ ‘A litre.’ ‘Really?’ they said. ‘You’re supposed to be on ‘sips.’’ ‘But I’m dehydrated,’ I said ‘and I’m thirsty. And my mouth was so dry I couldn’t speak.’

Days passed. The tone of the exchanges changed. I was put back on ‘nil by mouth’. The situation was spelled out: ‘The saline drip is rehydrating you’, they said. ‘Your stomach is not absorbing anything. We are trying to empty it of liquid – you will take longer to heal if you keep filling it with water.’ I nodded, let them know I could spell. But they could have saved their breath. Because this was no longer about thirst or rehydration. It was about control.

I was slowly regaining a feeling of dominion over my body. And revelling in the process. Told I needed to stop drinking but could suck on ice cubes, I made friends with the tea women, who brought me frozen litres of the things. ‘How many ice cubes am I allowed?’ I asked the doctors. ‘A few, within reason,’ they said. ‘But what is within reason?’ I said, and they couldn’t quantify it so I sucked continuously.

A standoff ensued. Visitors came. Friends and family. Opinion was more divided than I’d have liked. ‘I’m supposed to be nil by mouth,’ I said, ‘but I’m getting water from melted ice.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Because they don’t know anything about my condition,’ I said, ‘beyond the obvious. And I can’t just lie here and take it, can I?’ At this there were many ‘hmms.’ A long wait for a ‘good for you!’

They put another ‘non compliant’ in my notes. Told me I could dab my lips with a wet swab. I did for half a day. But by now my defiance had transcended itself. The taking of illicit water – at first for succour, then succour and show – had become a ritual. And as I sipped melted ice off a plastic spoon, touching cracked and bloody lips to the meniscus, feeling the gloriously cold liquid trickle down my throat and dribble over my chin and neck, I felt if not better then indescribably good.

This sensation was all I needed. It was both a vindication of my protest and what passed for its logical conclusion. Gradually, my body absorbed the saline and rehydrated. My thirst was quenched. I grew tired of water, began to take tea. My stomach emptied and I starting eating, walking. Still weak and spindly, I got ready to go home.

Before I left, a final cheek-puff, a final head shake. ‘Will this happen again?’ I asked as I was filling out my discharge papers. ‘No. It was a one-off,’ said a nurse. ‘That’s something we can be sure of: it won’t happen again.’ That’s a relief, I thought. I’m not sure I need another experience quite like that. ‘But if it happens again,’ the nurse continued, ‘you need to get yourself straight to A&E.’

I’ll always dannyboyle the NHS, of course. For its staff. For the social enormity of its undertaking. For its unique psycho-cultural synthesis of immigrants and clogs and the rugby pitch. For being what it is, despite what it is. But a stay in hospital is an affirmative business in other less obvious ways too. Mine helped teach me things about what it means to be alive. About the value of being contrary and willful. About the absurdity of it all.

Charlie Hill has written for TLS, New Statesman, Independent on Sunday, TimeOut and many others. His second novel, Books, is available from Amazon and in all good bookshops. Visit his website if you dare.