He was under the Eucalyptuses now. They rose tall and straight-backed, as sure as solid as anything in the world. Shredding strips of dead curling bark girt the trunks in patchy spirals and clung to the armpits of the branches. A magpie cried it’s drawn out wavering refrain – that most Australian of songs – before swooping down and landing on the ground in front of him. It glanced at him with a jaunty cock of its head, turned and took two long strides and then bounced back into the air.

The woman and her children had vanished and materialised on the other side. He reached the bottom of the hill and the water’s edge. A cold wind sliced into him from the harbour side. He drew into his coat and turned the collars up. He was glad of it now. He felt snug and protected like a child in swaddling clothes. The kids out crabbing had also moved away. They were picking their way slowly up the middle of the field. He could hear the occasional burst of laughter as they turned to each other. It was so vital and natural, so seemingly free of concern. It occurred to him that all the people in the park seemed to teleport away at his approach. In the perverse way of things, he began to hanker after some kind of human interaction – a smile, a nod, a friendly hello. He felt a little like the man standing alone at a party. He wondered if he was giving out signals that were subtly repelling others. If so, had it happened before? Had it blighted his career and relationships? Was there any way of telling and perhaps controlling it?

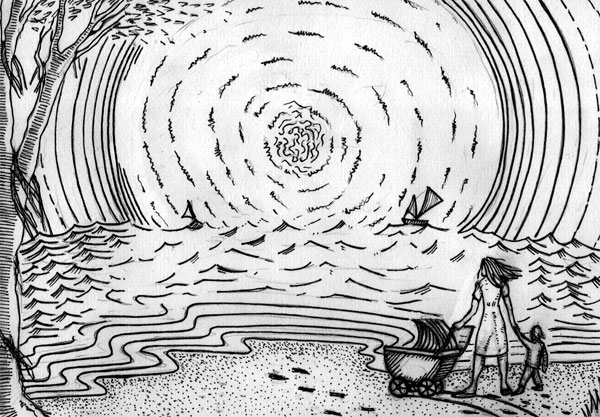

He got to a tangle of bushes at the edge of the park and cut up hill, along the second line of gums. The kids had gone. He looked for the mother with a brief flash of panic as though she were his wife or daughter and someone of significance to him. With relief he found her down by the shore, staring out over the water, flicked with gold from the setting sun. She rocked the pram gently, to and fro. The toddler played at her feet. It was like a piece of old celluloid that any moment was going to flare into dust and memory.

He was feeling tired now. Too much thinking. It had been a long journey and still it continued. No one knew when the journey was to end. He decided to cut short his walk. He would sit for a while and just be, empty his mind (including, if possible, that nagging something that skulked on the periphery). He would lay bare his senses to the wind, the smell of cut grass and the intermittent cries of the magpie. He would watch the woman and her children. That would give him pleasure. He could always finish the second loop of the park before he went home, if he felt like it.

He found his bench in a blaze of sunlight. The lowering sun struck him full in the face and he had to shade his eyes with his hand in order to see anything. This became tiring so he simply closed his eyes. He pulled his coat round him and dug his hands into his pockets. He squinted in the blaze. It looked like a smile and partly, it was. He tried to separate and distinguish the various sounds, starting with those nearest to him. Most immediately was his breathing. It rose and fell with a slight gravelly catch in it. A fly buzzed briefly as if in irritation. There was the soft thump of footsteps and then the thud as the ball was kicked. There it was! The gurgling spiral of the magpie’s call, as though in answer to the young sportsmen’s efforts (did he detect a mocking tone there?) Distantly there was a man’s deep bass, and in response, the unseasoned vibrato of a boy’s voice. Beyond this was the low dilating rumble of traffic, the rising whine of a car accelerating. He tried with concentration to hear the waves out in the harbour, pushing into shore, but all he got was the wind, near and far, rustling the leaves of the trees, playing about his face and bench, roaming over the ground and through the air, moaning indiscernibly. Rising and falling…

He woke with a start. But had he really been asleep? His thoughts had been so clear and he had been “feeling” so intently. But everything seemed different now. The atmosphere was changed, as though someone had stolen into the room and conversation had stopped. Indeed he was struck by the almost total silence. He couldn’t even hear the wind.

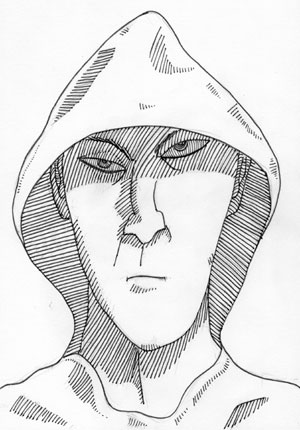

He looked round. There was a man sitting on the end of the bench. He started again. The man didn’t take any notice of him but continued to gaze out over the water in a dull, unseeing way. He was dressed all in blue and there was something stolid and heavy about him. His toes pointed inwards and a hood was thrown back on his head. In profile it was difficult to say exactly what he looked like. But the overwhelming impression was of someone lumpen and slightly draining.

Henry Bird’s surprise quickly turned to annoyance. Why out of all the places to sit in the park had he chosen his bench? Some people were so bad at reading a situation. Wasn’t it obvious that he wanted to be alone?

He glared at the man in an aggrieved way. Henry Bird’s once lustrous shock of black hair had turned white. He wore heavy black-framed spectacles with perfectly round lenses. Although the flesh of his face had withered and retreated, his nose remained large and defiantly hooked. He couldn’t see himself but together with his large overcoat drawn tightly round which made his head look like it was emerging from the flaps of a tent, the effect was slightly ridiculous. He looked like an angry little bird.

The man shifted in his seat and drew something from his pocket with a rustling sound. He dipped his head slowly to look at the crumpled white paper bag in his hand, then swung it round.

The man shifted in his seat and drew something from his pocket with a rustling sound. He dipped his head slowly to look at the crumpled white paper bag in his hand, then swung it round.

“Would you like a cough lolly?”

Henry Bird was so thoroughly disarmed by the question that before he knew what he was saying or doing he had answered, “Yes” and was reaching across to the extended bag. The other man took one too, and there they both sat, gazing out over the harbour, sucking on sweets.

It was difficult to keep up your indignation once you have accepted a gift from an enemy and Henry Bird’s vanished as quickly as it had arrived. And anyway, hadn’t he been yearning earlier for just such a simple human connection as this?

He glanced round again. This time his face was friendly and open. There was a link there now, however tenuous. He rolled the lolly about in his cheeks. Somehow the mutual chewing made the silence acceptable. It was like sharing a drink at the bar. Still –

“We live in a beautiful country don’t we?” he ventured.

The man continued sucking slowly and deliberately. He didn’t even turn his head. The silence drew and drew until the link between them began to sag and threatened to collapse. Henry Bird felt a prickling on the nape of his neck.

Finally the man spoke;

“I’m not from here.”

The words were distant and hollow and seemed to be uttered with great effort.

They continued sucking. Henry Bird was unsure whether it was the beginning of a conversation of the end.

He decided to try once more;

“Neither am I.”

He sensed the man’s head turn. He was looking at him. He glanced round slowly himself but in that moment the man swivelled back round to face the harbour as though their heads were hinged. He did the same.

“I’m from Scotland.”

He sensed the man smile. He was sure if it. Something too had changed in the atmosphere. There was an alertness, an engagement. The man was waiting for him to speak.

“I mean – my parents were Scottish. I’m Australian.”

Actually that wasn’t really true, or he didn’t feel it to be true. He was well travelled. He had lived chunks of his life in Europe and the States. He felt vaguely European but could never settle there. He loathed much that was Australian – the lack of cultural backbone, the obsession with sport, the brashness, the ignorance. Yet he loved it too. He couldn’t leave permanently, although part of him desperately wanted to. He never would now, but he kept this from himself. But how could he say any of this to a stranger? It was disloyal, contentious.

“Australian”, the man echoed. The word hung in the air. It seemed to fracture and sparkle with the light on the water.

“None of us are really. Except the Aborigines.”

Henry Bird smiled at the man’s boldness, and at his own timidity. He picked up the thread –

“I suppose even they came down from the north, through Sumatra and New Guinea – “

“None of us belong here,” continued the man, “ Look at the land! Nothing grows. Everything bites or stings. It wants us out!”

“And yet we stay,” observed Henry Bird, “None of us can leave. I wonder why?”

The man began to fidget at the question. His confidence seemed to go.

“Because it’s beautiful?” he asked meekly.

“Because it’s beautiful,” echoed Henry Bird.

He didn’t pick up on the change of tone. He was relaxed for the first time since he had left the house. All the little worries and doubts had gone, or at least were forgotten. He was enjoying himself on his bench, chatting to a stranger, as the sun went down over the harbour. He loved his wife and children but sometimes he felt a stranger to them. He knew he sometimes harped on the same subjects but that was because he was passionate about them, not because he was just blowing wind. He sincerely believed that Australia was a cultural wasteland and that this should be of national concern to the future of the country. That conversation was a dying art form, that civilization, as he understood it, was withering in the country in which he lived. He also felt overlooked. It was true that he had been a success and it was partly because of this that he felt now that he should be better recognised. Since he had slowed he had been sidelined, and since he had retired, largely forgotten. All that striving and achieving. What was it for? He was bursting with knowledge and experience that was somehow unwanted. He was looked upon as an old man and was in some way meant to be grateful. His children mocked him for his pomposities, considered him a buffoon, and of course, he played to the gallery. He had, in many ways, become a pompous buffoon. But it was a role he felt increasingly strait jacketed by. He had a nobler, greater performance yet to give. Perhaps he would start on this bench, in the presence of a stranger.

“Do you know anything about light? How it’s formed? It’s amazing when you understand how.”

At that moment the sun dipped below the horizon, swirling yellow rimmed with black. Suddenly the colour was leached out of everything. It went very dim.

He looked around as if emerging from a deep sleep. The park was very gloomy. The shadows of the eucalyptus trees fell one upon the other in an unbroken line, like a wall. It had become eerily quiet. The ball kicker had gone. They were alone.

He turned to the man. The latter was turned also and was facing him for the first time. He almost started in surprise. He hadn’t known what to expect but it wasn’t this. The face was lopsided and mask-like. The eyes were almond shaped, angled down and set at slightly different levels. They were dull and black from shadow. The expression was completely blank.

Then he noticed that the man was holding something out towards him. At first he thought it was the bag of cough lollies and nearly motioned it aside with a, “No thanks.” But then he saw that it glinted. It was a knife.

“What’s in your pockets? Give me your wallet,” breathed the man.

Henry Bird was baffled. At first he thought the man for some reason wanted to check his identification. It was only when he was drawing the wallet out that he realised what was happening. He felt something drop within him, like a sharp rock into the icy waters of a river.

The man snatched the wallet and bent it open. He plucked out the notes and with a grunt dropped it back on the bench. It bounced through a gap in the slats and fell to the ground. The man shoved his hands in his pockets, and shoulders hunched, shambled off into the gloom.

Henry Bird remained where he was sitting. He left the wallet where it had fallen. He felt light, empty. For some reason the first thought that entered his mind was of the taxi driver he had argued with the week before when they had gone to the theatre. He had been quite rude to the man.

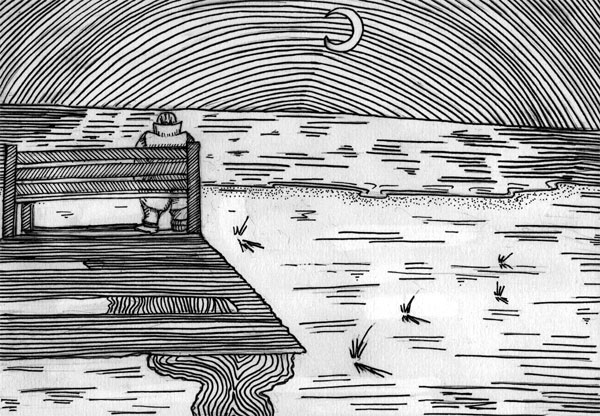

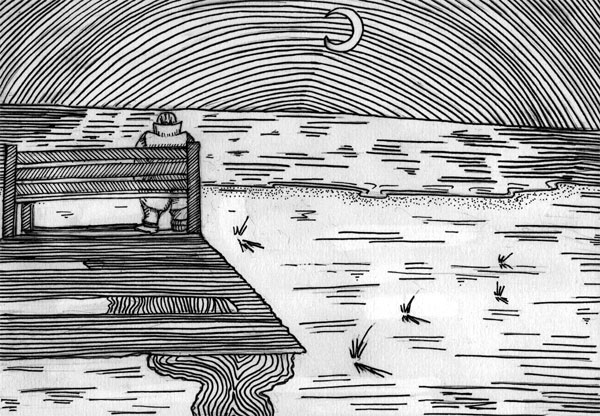

Darkness fell and the moon rose. He continued to sit. Faintly he could hear the waves rolling out on the harbour.

Written and illustrated by Harry Chapman.