Much can be learned from the books we read as children into which journeys we take as adults. With schools returning and the prospect of travel on the horizon, author and travel writer, Sarah Tucker, suggests we should take heed from Into the Woods, ‘Be careful the tales we tell, it casts a spell…’

My bookcase is bursting with children’s picture books. No, lockdown has not made me regress into my inner child, or second childhood, or whatever Freud or Jung said I would do; rather I’ve returned to university to study children’s literature. (Indeed, rather unwittingly, thanks to lockdown I seem to be immersed in student life a little more than I’d have thought, being confined to my room in Cambridge’s halls of residence.)

To the point, though, it’s surprising how many children’s books, especially those with predominantly visual texts, are about journeying. Exploring, adventuring, courage, compassion, creativity, accumulating with each page turn as our heroes and heroines open the door, drop down the hole, meet the dragon, fly on the giant bumble bee, talk to the animals – and all sans adults, who are usually predisposed as ignorant, stupid, insular, greedy, needy, materialistic, naïve or, ideally, absent through desertion or death.

This latter trait, I am told, gives agency to the child and makes them the instigator rather than that loathsome social media idiom, the ‘follower’. It’s also probably a fair representation of how children see the grown-up. Particularly during these lockdowns, they may have been bemused and probably depressed by the fear, apathy, anxiety, narcissism, neurosis, negativity and nastiness of the adults they’ve seen in the round-the-clock television coverage.

My love of travel started as soon as I could walk. I was endlessly trying to escape, twice out of my bedroom window, recruiting some other reluctant six-year-olds on my quest to Go Mad in Dorset/Devon/Cornwall – even Barking. They weren’t as determined as me. I remembered this when I started travelling as a single mother with my own son – much more fun than when his father was with us – and I was re-introduced to the books that shaped me as a child.

I didn’t have the benefit of ‘How Much Do I Love You’ and ‘We’re Going on a Bear Hunt’, or even ‘Tintin in Tibet’; mine were the Penguin editions of Cinderella and Snow White and The Elves & the Shoemaker. These also fuelled my independent streak, my need for self-sufficiency. I never bought into Cinderella, not wanting to be a glamorous victim-in-stasis waiting for a Prince to marry me. What is wrong with just saying ‘thank you’? Why marry him?! And why can’t I be the one killing the witch and choose to rescue him? Although, if I’m honest, I would have probably left him to sleep a little bit longer as I could have had a lot more adventuring and swashing and buckling without having to do his washing, cooking, cleaning, ironing etc. And then there was Snow White, with her predilection for apples, which still makes me giggle now. Fiction works in odd ways, and children’s books have a habit of sinking into the subconscious in a way adult books do not.

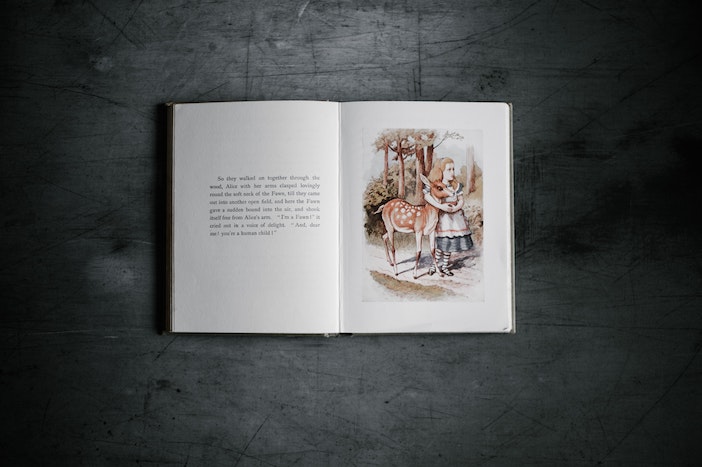

My story was Alice in Wonderland. Alice ventured down the rabbit hole, meeting mad, bad and dangerous people along the way – and moved on. There was no prince, or wish to meet a prince, no rescue required, no sweeping-off-feet, just a journey and exploration of interest, to gain courage and insight, compassion and creativity. She didn’t play her cards right (literally) and neither did I – I don’t play the game and have been told on very many occasions – but it’s given me the chance to experience plenty and enjoy the ride.

But I digress. Have you noticed how many children’s books focus on the concept and conceit of travel? And rather than telling them to keep on track, to go off it. Parents – prepare to panic. They’re told to explore, to meet new people, to ‘boldly go’, and all that. The books have a linear feeling to them, but the research I’ve done shows children look at the front cover then go to the back pages, to see where the journey goes, and then to the middle. They never start at the beginning. That’s where adults start, but not children. Theirs is an innate curiosity. They are creative, and able to think for themselves given the tools, the courage and the opportunity.

That’s why my thesis Thinking Out of the Book is about encouraging bookshops and libraries to have ‘thinking sections’ rather than categorising books by age. Which is nonsense. Age is a nonsense. Development milestones are a nonsense. I was reading the Sunday Times colour supplement at eight. As long as it has pictures, it’s decipherable. Indeed, a child can guess what is being said better than an adult, as they are more aware of the social construct than their parents. In lockdown most children became aware of the fact there is no material difference between a Saturday and Wednesday. The Matrix, if you like, was revealed.

That’s why my thesis Thinking Out of the Book is about encouraging bookshops and libraries to have ‘thinking sections’ rather than categorising books by age. Which is nonsense. Age is a nonsense. Development milestones are a nonsense. I was reading the Sunday Times colour supplement at eight. As long as it has pictures, it’s decipherable. Indeed, a child can guess what is being said better than an adult, as they are more aware of the social construct than their parents. In lockdown most children became aware of the fact there is no material difference between a Saturday and Wednesday. The Matrix, if you like, was revealed.

Then there is how children are travelled. And this is where the reality of their adventures parts with those they read in books. Thirty years of travel journalism behind me and I still observe children being travelled like handbags, taken out on special occasions and slotting into that feeling of happy holidays. I remember one hotel in New York trying to appeal to the family market with their chocolate-flavoured bubble bath. Net result: children being unwell because they were drinking the bathwater. One gets the feeling that those in charge either don’t have children, don’t like the children they have, or don’t even see the children they do have. And don’t get me started on kids’ clubs. Kids’ clubs are appreciated more by the adults than by the children – when empirical research asked the children what they thought of the reality of the idea, it was to give the parents a break. Then why have children if you are always asking for a break from them?

I have friends who didn’t want children, and others whose life had no meaning without them. I was somewhere in the middle. I had a mother who was a martyr to the cause but whose parenting work ethic was disproportionate to the amount of whinging it produced. This meant I spent a lot of time in my room thinking, creating and, as we know, finding a way to escape and trying to recruit others on my Five Go Mad adventures. But my mother’s protestations did leave me with one thought; you need a licence to drive a car, buy a dog, have credit checks for getting a mortgage, but there’s no provision or permission required for having a child. But that’s a whole different article.

Travelling with a child for me has been a joy. And now mine is grown up, reading children’s stories – admittedly in that linear adult way – I’m rediscovering the pleasure of travel through a child’s eyes. Alice, in her Wonderland, pointed out ‘what good are books without pictures and conversation?’

Travelling with a child for me has been a joy. And now mine is grown up, reading children’s stories – admittedly in that linear adult way – I’m rediscovering the pleasure of travel through a child’s eyes. Alice, in her Wonderland, pointed out ‘what good are books without pictures and conversation?’

Quite. That is what travel is about. Pictures and conversation. Travelling does that. Of course, the children are often just adjuncts to the dreams of their parents as they travel – as well as being the sun around which all their activities revolve, naturally. But we actually do learn more from our children than they learn from us. How many parents actively listen to their children, and realise that ‘out of the mouths of babes’ comes not just truth but ideas that break the boundaries of binary thinking.

It’s understood that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl’s most famous story, was influenced by his daughter, Sophie, who suggested he re-write it another way because ‘children don’t think like that’. Children take you on different journeys, different paths, and as the late Sir Ken Robinson claimed in his celebrated TedTALK (watch if you haven’t seen it) about education killing creativity, we make linear thinkers out of lateral thinkers, and it shows in the way we travel.

So, when we are allowed out, and given our COVID passports or whatever the powers that be decide will be required, take account of how you have behaved during this lockdown as parents. Have you shown courage, compassion and creativity? Or have you shown fear, neurosis or narcissism? Do you want a child who is going to be a leader or a follower?

Use the opportunity of travel to explore that idea of exploration. It takes courage and humility to do it.

Sarah Tucker’s series of podcasts THINKING OUT OF THE BOOK, with influential thinkers talking about their favourite children’s book and what makes them think, can be found on the Cambridge Changemaker University website from 20th March 2021. Access the link on Sarah’s website sarahtucker.info.

Photos by Annie Spratt, Nathan Dumlao, Brian Mcgowan, Robyn Budlender – provided by Unsplash