This weekend we begin a travelogue with a difference. Leaving his comfort zone as far behind him as he can, Tom Garton seeks thrills on horseback in the central Asian steppes, yurt camping under the stars. But not everything goes to plan. In this first part, they arrive in the Kyrgyz capital, Bishkek, for Soviet-era hospitality and some unconventional R&R…

“Are you up for an adventure?” Ben called me late one night in February. “How do you fancy spending two weeks in Kazakhstan?”

Six months later, I was in the back of an unlicensed mini cab driving from Almaty to the Kyrgyz border. Ben had the beginnings of bronchitis. I thought we were going to die.

We’d arrived in Kazakhstan after a nine-hour flight with a layover in Astana, the country’s recently created capital.

Astana had been briefly terrifying. Immigration felt like a throwback to the Cold War, and the city’s skyline, built by architects such as Norman Foster and Zaha Hadid, looked like something out of The Hunger Games.

Now we were in Almaty. Unfresh off the plane, hurtling along a semi-made road in the back of a God-Knows-What-Car, with two chain-smoking-chaps upfront aggressively conversing in a language we didn’t understand.

We’d come to escape our humdrum lives in late-capitalist London. For two weeks we’d travel through Central Asia, making our way through the most remote places still left on Earth. We’d trek on horseback through the Kyrgyz mountains, stay in yurts, and drink unfermented goats’ milk. We’d see the stars, and reconnect with a more elemental, authentic human existence.

That was the plan.

Our first stop on the itinerary was Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital. Rather than book a direct flight from London, we’d decided to travel to Astana, then Almaty, then charter a cab for the four-hour journey to the Kazakh-Kyrgyz border, and, then finally, on the other side of the border, pick up another cab from the border into Bishkek.

At the airport, we were met by our friendly driver who had arrived in order to harass us for our business. Accosted, and without any back-up plan, we agreed on a fee of 10,000 Tenge for the journey to the border – roughly £20.

This is how business is done out here. Although you can use Uber in the centre of Almaty, outside of the main town you’re forced to rely on marshrutkas, cramped minibuses that take forever, or unlicensed taxis manned by characters of questionable probity. Against my better judgment, throughout the trip, we opt for the latter.

On the road to the Kyrgyz border at Korday, the view is spectacular. Once you leave the satellite towns and petrol stations at Almaty, you are in steppe-land, where barren, golden wastelands stretch out interminably. Occasionally there are young boys riding horses, silhouetted in the sun; and in the near distance, the foothills of the Tian Shan mountains.

The border at Korday is at the end of a neglected piece of road crossing the river Chu, which acts as the dividing line between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. A large, light-blue arch emblazoned with Kazakhstan in Cyrillic marks the crossing.

The driver points at the arch, “Granitsa”. Border.

We get the picture and step out of the car. There are a few kiosks selling bottled water and Cokes.

We heave our luggage on foot and join the sombre crowds queuing at the crossing. The border officials seem confused, we’d only entered the country eight hours before. “Speak Russian?” They ask threateningly. I shake my head. They laugh and say something presumably offensive. Satisfied, they send me once more out of the country and onto the Kyrgyz side.

Passing through the Kyrgyz border is more alarming. They take away our documents from us, and analyse them in a separate room.

Less than 24 hours ago I was in the BA lounge at Heathrow with a G&T, leafing through The Economist. Now I’m paperless in no-man’s-land between two former Soviet republics.

Ten minutes pass and a Kyrgyz border official emerges with our passports. We check them. All is fine. We are free to go. We cross the bridge over the River Chu into Kyrgyzstan.

With a population of just under 6 million, Kyrgyzstan is one of the smallest and poorest “stans”. It is also one of the most volatile. Recent revolutions in 2005 and 2010 led to the toppling of two presidents. During the most recent revolution there were allegations of mass killing, gang rape and torture.

As we cross the border, this volatility is immediately recognisable. The Kazakh side of the crossing is dilapidated but fundamentally sleepy, but in Kyrgyzstan we’re immediately confronted by a gang of up to twenty taxi drivers.

“Amerikanski, Amerikanski!”

“We’re not Americans. We’re British!” Ben says, still half asleep.

The drivers are nonplussed, until one of their group whispers some kind of translation.

“Ahhh! Meester Bean,” they cry. I manage a weary smile.

Somehow our bags are taken from us and we are led to a car. Our driver is a foot taller than the rest of the group, and also the most terrifying. His car has a dent the size of an anvil in the passenger seat, and one broken headlight.

We start driving. Like many poor countries, the outskirts of Bishkek are lined with cabins built of corrugated iron. Old men and women walk in ditches by the side of the road dragging shopping bags behind them.

This driver is a thick-set maniac. In his late 20s, he is speeding down the unfinished road, overtaking anyone in front of us. Russian-speaking rap is booming out of the vehicle. Suddenly, and abruptly, he pulls into the side of the road.

He wants his money now, but we’re still nowhere near our hotel and we don’t have any som. The driver calls a friend and drives us further into Bishkek. I am certain that he is calling his mates to beat us, rob us and leave us for dead.

To our surprise, he drops us, at the doors of our luxury, five-star hotel, The Orion. We pay him, and a brief moment of terror is over.

The Orion, our home for the next few nights, is the most luxurious hotel in Bishkek. Built in 2016, it is located on Erikndik Boulevard – the Knightsbridge of the Kyrgyz capital – home to a Max Mara boutique and the British Embassy. The hotel’s illustrious former guests include Steven Seagal.

I’m taken to a vast bedroom, and I instantly sleep.

When I wake up, I notice my surroundings for the first time. Although the Orion was only built two years ago, the hotel feels like an ambassadorial residence from the 1960s USSR. It’s James Bond meets Louis XVI.

The bedroom floors are carpeted in luxurious blue and gold, and the bedside cabinets are mahogany and gold. The bed is also made of mahogany, with a neo-baroque headboard. The bathroom is pure marble and gold.

I have a shower, and head down to the bar for a Kyrgyz vodka.

The bar has the same grand ‘50s Soviet style as the bedrooms. Ornate wood panels, and a marble floor. There are a few local businessmen in the corner. I’m given a heavy ashtray along with the vodka – neat, in a large crystal glass. There is a rather extensive menu of cigars and cognacs. I forget that there are places in the world where you can still smoke inside.

I’m just starting to enjoy myself, when Ben joins me in the smokers’ lounge and instantly starts spluttering again. He’s making a meal out of this bronchitis.

“Do we have to be in this smoky bar?”

Reluctantly, I sink my vodka, and we head into dinner.

The restaurant is a vast hall next to the reception, with a huge ceiling. There must be enough space for a hundred or so diners. We are the only ones there. We are handed poster-sized menus in a French-style font. Italian dishes are mainly offered, alongside a lot of horse meat.

Horse meat is the staple of Kyrgyz cuisine, but I can’t face sampling the local delicacy just yet. The food at the Symphony is the best European food you’ll get in Bishkek. The pastas are good. The salads are good. The meat is good. It’s the standard of a four-star hotel in Rome.

But you don’t come to Bishkek for the food; you come for the adventure, the thrill.

The problem is that Ben won’t stop banging on about his bronchitis and now our entire plan seems to be crumbling before my eyes.

We’re supposed to be heading to the small town of Kochkor in a few days’ time in order to get some horses and trek to Song-Kul Lake – a beautiful inlet set within unspoiled hills. The pictures of these places are absolutely stunning; it’s the most remote, picturesque landscape imaginable today.

But Ben’s already pouring cold water on it.

“I’m not sure I’ll make it,” he croaks, forking his vegetarian pasta against the backdrop of the grandest dining hall in Kyrgyzstan.

I’m reminded of the honourable Captain Lawrence Oates, and the ever-dwindling dignity of the modern British man. In days gone by, he’d just shut up for the next few days as we head into the wilderness, before nobly stepping out of a yurt one morning to die. How were we going to make a success of Brexit when this pathetic creature was representative of the modern Briton?

I tell him to go to bed and have a few more vodkas in the smoke-filled bar.

The next day, feeling more sympathetic, I let Ben recuperate, and decide I need a massage.

The effusive concierge in the Orion books me a massage, assuring me it is the best quality in the city.

A taxi arrives. We drive past warehouses and dirt tracks. The steppe outside of the window is an endless, faded, musky yellow. Surely, this isn’t right? I think. Wouldn’t the best massage in the city be inthe city?

It becomes quite clear that the concierge has definitely got something wrong. In fact, he has booked me in for one of the most bizarre experiences of my life: a deep-tissue massage on an industrial estate on the outskirts of the Kyrgyz capital.

The “baths” are housed next to a large hardware store. The building itself resembles a ‘90s leisure centre, as overweight dads and stick-thin sons mill through the turnstiles into the single-sex areas.

The staff on the door are perplexed as they take my money. I must be the first tourist to ever turn up here.

I get changed and am given an inadequately small, white towel to cover my body.

The baths attendant is half my size both height and width-wise. Initially, we’re lost in translation. He is bewildered by my presence. I can’t blame him. I shouldn’t be here.

Fortunately, the word massage sounds the same in any language. I lay on a thick Russian accent, and he has a lightbulb moment, leading me through to a dark room, filled by the low growl of obese men snoring.

The attendant urgently taps the shoulder of a lump of body mass and points at me.

I’m led through to a tiled floor with greening curtains that loosely demarcate booths. It resembles an East German morgue.

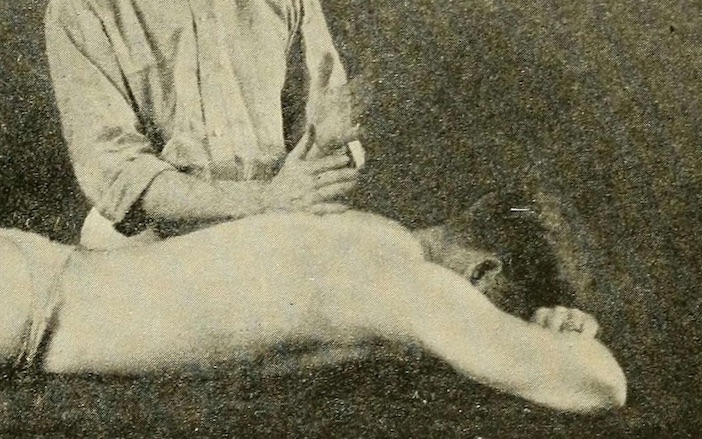

In a moment of subconscious masochism, I point to the full body massage.

The obese masseur isn’t wearing a shirt. I can feel his sweaty, brittle, engorged stomach rubbing against my head, as he kneads my back.

My head is locked into the operating table. All I can see is the grimy tiles.

Behind me I hear two voices. He has invited someone into witness the procedure. He seems to be giving a tutorial.

After an hour in the saddle, I’m told to leave. After wandering through some saunas, I get a taxi back to the Orion.

My taxi driver is a young man, about 21.

“Where are you from, sir?” He asks in fluent English.

“London.”

The son of a female linguistics professor, Asyl has a degree in economics from the local university and speaks fluent Turkish and English. At around 5’6, he wears a pressed, grey polo shirt. A large tribal, wave-like tattoo is splayed out across his neck.

In the car we immediately strike up a rapport, and discuss a range of matters, chiefly women, money and fast cars.

Asyl is shocked I went for a massage on the industrial estate.

“I know very good massage places,” he says.

He describes a range of more exotic-sounding massages, which I decline.

Asyl is not just a taxi driver. He has carved out a role as a fixer for Bishkek’s nascent tourism industry. Whatever you want, Asyl can get.

He describes how he scored a large quantity of cannabis for a party of American bros. Apparently, it’s very difficult to buy drugs in Kyrgyzstan. The police are very strict. Weed is possible. Nothing else.

“Whatever you want, Tom, I can get,” he repeats.

“Could I ride a horse, Asyl?” I ask.

“A horse?”

“Yes.”

“Yes. Why not?”

He seems bemused by the idea that someone would want to experience a traditional pastime, rather than smoke weed and drink cheap vodka.

“Meet me tomorrow morning outside your hotel. Early.”

When I get back to the hotel, I can still hear Ben’s cough hacking down the hallway. We’re not going to get out of this city anytime soon.

To be continued…