Imagine the Jedward twins being made to dance to their deaths on stage. Or John and Edward being put in a nail-studded barrel and rolled down the street. Imagine making Brian Dowling wear red hot iron shoes for the curtain-call. And Jim Davidson, The Krankies or Christopher Biggins having their eyes plucked out. So everyone can live happily ever after.

It won’t happen. But that’s what really should happen in pantomimes. Traditional pantos should carry ‘PG’ recommendations if they were true to their gruesome roots and Grimm sources. Following in the footsteps of the Brothers Grimm along the ‘Fairy Tale Road’ is an eye-opener. For Marchen Strasse in Germany is the original Panto-land. It is where all the seasonal booing and festive hissing began.

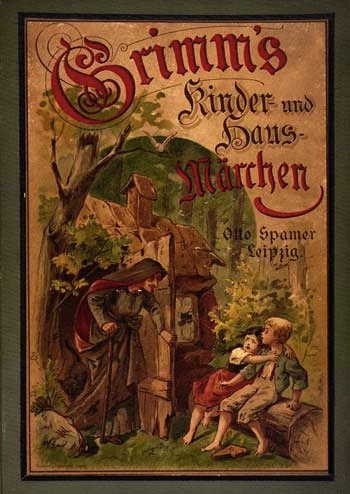

Grimms’ Fairy Tales (Kinder und Hausmarchen) was first published in 1812. It is still the most successful book of all time. It has been re-printed more times than the Bible and Harry Potter. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were scholars and originally collected their ‘Children’s and Household Tales’ to preserve and define German cultural identity at a time when their country was under the suppression of Napoleon.

Though only forty are well-known, the brothers collected over two hundred stories. Originally, they were for adults. They were violent and contained sex scenes. Rapunzel had it off with the prince. Snow White, or Schneewitchen, was stripped naked by the dwarves and given a bath after she had bitten the poisoned apple. Her stepmother had her feet set on fire and the Ugly Sisters in Cinderella had their eyes gouged out. The frog in The Frog Prince was repeatedly thrown against a wall.

Though only forty are well-known, the brothers collected over two hundred stories. Originally, they were for adults. They were violent and contained sex scenes. Rapunzel had it off with the prince. Snow White, or Schneewitchen, was stripped naked by the dwarves and given a bath after she had bitten the poisoned apple. Her stepmother had her feet set on fire and the Ugly Sisters in Cinderella had their eyes gouged out. The frog in The Frog Prince was repeatedly thrown against a wall.

When the stories were sanitised for children as ‘a manual for good manners’ they emphasised the virtues of thrift , loyalty and rustic simplicity. But even the toned-down versions were banned after the Second World War as Nazi propaganda. Through revision and translation, the story-lines have been dumbed down, made more age-appropriate and, typically, if comfortingly, more PC – in the original story, for example, Gretel is the only one who gets tired walking through the woods – though there are still more evil female villains than men.

Such things and more you learn if you follow the Fairy Tale Road, which connects seventy villages over four hundred miles through the Hessen region of Germany. “The books have appeared in over 120 languages,” says Herr Ling , the curator of the Bruder Grimm Haus in Steinau, an hour north of Frankfurt.

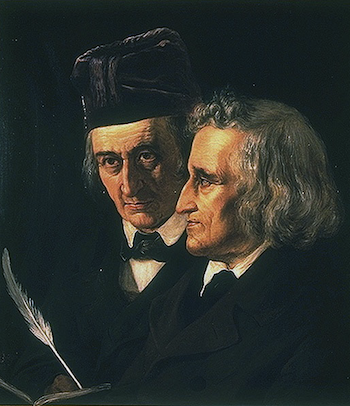

Jacob (born in 1785) and Wilhelm (1786) moved there after their father, the son of a clergyman became a local magistrate. Their birthplace in Hanau (twinned with Dartford, to continue the Grimm theme) was destroyed in the Second World War. On its site there is a statue of the two brothers looking very scholarly – or just bored from having to look so serious and so very scholarly for so long.

Jacob (born in 1785) and Wilhelm (1786) moved there after their father, the son of a clergyman became a local magistrate. Their birthplace in Hanau (twinned with Dartford, to continue the Grimm theme) was destroyed in the Second World War. On its site there is a statue of the two brothers looking very scholarly – or just bored from having to look so serious and so very scholarly for so long.

Serious academics, they wrote forty books between them including a German dictionary and the seminal book on German grammar. They were, to all intents and purposes, the founders of German linguistics.

“The book on grammar is the greatest book in our language, “ says Herr Kling, his laugh echoing around the stone walls of the half-timbered Fachwerkhaeuser burgher-house where the Grimms lived from 1871-6, the only Grimms’ home still standing.

“Come upstairs,” he invites me, leading me up a dark spiral stone staircase in the Grimms family home, “I want to show you my etchings”. In the shadows he looks like the huntsman in Snow White.

The etchings he wanted to show me were by a younger Grimm brother, Ludwig Emil, who illustrated his brothers’ books. “Most of our idea of fairy tales come from the early printers and illustrators,” Herr Kling explains, “the Grimms blended oral with literary traditions. They read the classics and listened to locals. Local washerwomen and spinners chatting away in the Spinnstube were great sources for their stories.” One their biggest inspirations was a publican’s daughter, Dorothea Viehmann, who was the source of Aschenputtel, or Cinderella to us. Similarly, Marie Hassenpfug, a friend of their sister Caroline, was another source of plots. “And many stories, like Sleeping Beauty, were French,” he tells me, “the Grimms lived in a French land after all.”

The famous fairy tales’ first English translation, as ‘German Popular Stories’, appeared in 1823, and evolved into popular culture in the decades following; Cinderella being performed as a pantomime at London’s Drury Lane Theatre in 1905, the Disney cartoon of Snow White reaching cinemas in 1937, and the brothers’ stories have fuelled Disney ever since. Though immediately after the Second World War the books were banned because they reputedly espoused Nazi cruelty and the ideology of the Third Reich.

Theirs is a rich cultural heritage; Kassel on the Fulda river was the site of the country’s first observatory, now a National History Museum. Its Wilhelmshohe Palace has Germany’s second-largest collection of Rembrandts. And, naturally, the city also has a Grimms museum, full of Grimm things like the brothers’ original hand-written annotated first edition, now worth around £2m.

“The stories are not localised, they are largely placeless and timeless,” says the museum’s director, Dr Lauer, “Rapunzel may have let her hair down in Steinau Castle. Hansel and Gretel may have walked in the Psessart woods. The Travelling Musicians may have left from Pyrmont.” Dr Lauer may reassure me that they have wide appeal but it’s clear the region provided the inspiration for the brothers.

Opened in 1973 Germany’s Fairy Tale Road winds through the Fulda Valley in Gottingen, where the brothers taught, and Marburg, where they studied law. It passes Gothic castles like Trendelburg and a lot of dark forests; though the only elves to be seen are in Lauterbach, the centre of the German gnome manufacturing industry.

“We do have hungry wolves,” says Gunther Kopeck, whose family owns the world’s only ‘official’ Sleeping Beauty castle, Dornroschenschloss in Sababurg, twenty miles north-east of Kassel. And the region’s castles have inspired more then the brothers in their time; Walt Disney’s castle was based on Neuschwanstein in Bavaria. “Snow White may have been based on a true story,” my host tells me, straight-faced, “of a noble girl with an evil step-mother who was befriended by a group of iron ore miners.” Can it be? “And her father was a mirror manufacturer.” More than just coincidence, surely. “The original talking mirror is on display in Lohr am Main,” Herr Kopek continues, offering evidence.

“And Sleeping Beauty is not make believe!” He insists, leading me up another spooky staircase into another spooky turret, “we have briar roses and a thorn hedge. And woodcutters working in the Wald!” He smiles as we look out over the countryside from the 230 Euro-a-night tower. The castle operates as a hotel and boasts the oldest animal park in the world, going back to 1571.

On the way down the winding staircase I spot a spinning wheel standing by a large locked door. I am drawn to it, even instinctively. “Please don’t touch it,” Herr Kopek says suddenly, as if warding me from danger.

As if anyone in a hundred years would ever want to kiss me awake. Not even the Brothers Grimes.

For more information about the Fairy Tale Road and the tours available along its route, including places to stay, visit the Germany Travel website and the official Maerchenstrasse website.