Classic and contemporary novelists wax lyrical on the inspiration gleaned from a walk in nature. Virginia Woolf, Henry David Thoreau, Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) all ventured into the great outdoors to inspire their writing. I myself walk around Richmond Park, avoiding the rutting deer and the sixty-mile-an-hour cycling MAMILS, and find a clarity of thought in this blissful portal far from the madding crowds of four-wheel drives and parking attendants.

Perhaps our most celebrated literary figure, Jane Austen, was a country girl and it was her time in Hampshire and the surrounding countryside which inspired her novels. I learnt this amongst many other anecdotes as I travelled to the village of Chawton, where she lived with her family, visiting as part of a new initiative, Creative Footsteps, which takes in some of the most illustrious places in the region, principally connected to Austen and her writing.

Woodcut print of Jane Austen (courtesy of Jane Austen House museum)

Austen wrote about what she observed around her, and, while she is possibly best known for her association with Bath, she was only there for a very short time, and only at the bequest of her father, who died there, leaving the family without fortune and favour in society. Indeed, she detested the place, in much the same way Virginia Woolf detested Richmond. By contrast, the place Jane Austen adored, and which inspired her to write her novels, is Chawton.

Born in 1775, Austen has always fascinated me; she appeared to write romantic fiction but read her work more deeply and there is a careful insight into the historical repression of women, even those born into money and high society. The irony of Austen’s face being imprinted on a £10 note would not be lost on her. The loss or lack of money in her own family, the importance of money for safety and security, as well as acceptance in society, is an undercurrent in each of her novels. There is almost an unspoken affirmation ‘if you marry a wealthy man, you earn every single penny of it’, illustrated by the tremulous journey of each female protagonist.

Whether the journey was worth the reward is uncertain. Jane always ended her novel at the marriage ceremony. This coupled with the constant anxiety and tempered anger etched through her novels, spoken by characters such as Mrs Bennet in Pride and Prejudice wanting her girls to marry money, or Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, losing John Willoughby to a woman who has money. Women lacked opportunity for financial independence, and in many ways still do.

Chawton House (courtesy of Chawton House museum)

Walking through the village and visiting the magnificent Chawton House, which Jane referred to as the Great House, offers a fascinating and rewarding insight into how she wrote about what she observed. With its fields full of sheep, the country cottages, neat with mature trees and heavy thatch, it’s the opportunity to visit her house which sends shivers of excitement running through me. Now a museum, I am told by my guide, Jane Hurst, little has changed from Austen’s time, which makes it all the more enchanting, knowing these walls have looked down upon her world.

Austen moved to Chawton in 1809, living in a cottage granted to her by her brother Edward, who inherited the ‘Great House’, and stayed until 1817. It was here where she wrote, on the smallest of writing desks, inspired by the characters and politics of village life, where everyone knew everyone’s business – or thought they did. As I wandered its streets, I expected Mrs Bennet to come running round the corner scolding Elizabeth for not putting on her bonnet straight, or Mr Elton sermonising about the beauty of nature, or even Darcy, astride his horse with Bingley in tow, riding across the meadows in search of a lake to dive into.

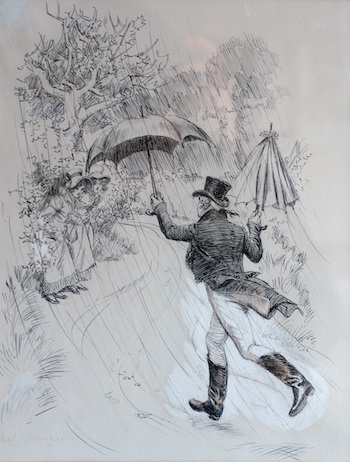

19th c lithograph (courtesy of Jane Austen House museum)

The village had a pond at its heart, where coaches would pass and make a stand off as to which had right of way. The locals, including Jane, would sit and watch the arguments, debating to see who might win and how. My guide, Jane, and her friend Pat Lerew, a schoolteacher in nearby Alton for over thirty years who gained an MBE for her services to the community, are as knowledgeable as they are passionate about Austen and her world.

They both provide excellent, amusing and animated accounts of life in Chawton and Alton. Most entertainingly, Jane Austen was something of a gossip, and not an accurate one at that, and her letters reveal a lot about what she thought of and heard about the inhabitants of Chawton and their goings-on.

The driveway alone up to Chawton House will leave any visitor breathless, and remind you how Elizabeth Bennett felt on first seeing Pemberley. It is easy to imagine horse-drawn carriages trotting up, passing the church to the right – where a small statue of Austen looks over the surrounding meadows and the South Downs, and the graveyard where Jane’s mother and sister are buried, both of whom survived her by many years. Jane herself is buried in Winchester Cathedral, as the daughter of clergy, rather than as one of the most acclaimed and successful authors of all time.

Chawton House itself is well worth a visit – particularly for its library, which includes works not known to exist anywhere else – and runs many exhibitions and talks each year, celebrating the works and ideas of women writers. Jane Austen would have approved. On my visit, they were preparing for a Halloween exhibition focusing on the gothic landscape and gothic apocalypse – oddly appropriate in the surreal times in which we live. You can take afternoon tea there, in what would have been the scullery and in the courtyard, and then take part in the garden trail, which allows visitors to follow in Jane’s footsteps.

During the Creative Footsteps festival, I chose to head out of Chawton to the nearby village of Selborne. Here, among twenty-five acres of gardens, is the house of Gilbert White, the pioneering English naturalist, ecologist and ornithologist. White’s work, The Natural History of Selborne, remarkably, is the longest published work after The Pilgrim’s Progress and Shakespeare (gilbertwhiteshouse.org.uk). First published in 1789, it’s still in print.

Gilbert White’s house (photo courtesy of the Gilbert White House museum)

The house has now transformed into a museum of renowned British Explorers, and his home and gardens, which still feature many derivatives of his 18th century plants, offer a fascinating insight into a man. A man who, like Jane Austen, never married, and who devoted his life to passion for nature and study of the flora and fauna around in village. Although White was a campaigner for getting closer to nature, and is often regarded as an 18th century Attenborough, he never managed to venture far from his village for his aversion to travelling by coach – the suspension was appalling.

His writing, not merely confined to scientific analysis, is witty, warm and colourful, made so in part by choosing to write about the inner lives of the animals he observed. Most famously, he wrote of his pet tortoise Timothy, the nation’s oldest pet, who he describes in his book as being of the most ‘amorous kind’. Timothy, incidentally, survived Gilbert, and it was only discovered after the tortoise’s death, that ‘he’ was, in fact, a ‘she’.

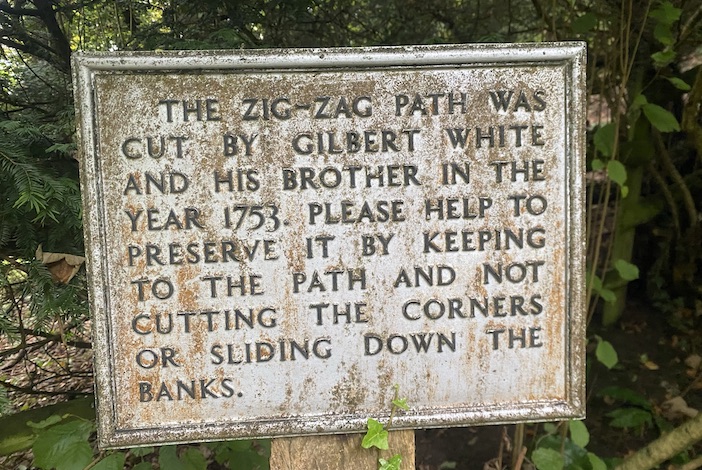

I spent the last hour of my day walking up the Zig-Zag Trail neighbouring White’s home, which is a literal zig-zag path up Selborne Hanger, one of the highest hills in Hampshire. This unique path, cut by White and his brother in 1753, scales the steep ascent with a series of short paths, and rewards one’s perseverance with stunning views over the South Downs.

Taking in the vista, I gather my thoughts, and consider these two emblematic figures of Britain and Hampshire. White never met Austen in person although they were both alive at the same time. Jane writes about White’s nephew in her letters, and having learnt about both characters following in the Creative Footsteps of these characters, I sense, with their love of the countryside, their keen observation of their surroundings and sharp sense of humour, they would have enjoyed the company of the other.

For more details about Creative Footsteps or any of the places mentioned in the article please visit www.easthants.gov.uk.

For more information about Jane Austen House museum and gardens, including details of current and forthcoming exhibitions, please visit www.janeaustens.house.