Think of cities in the United States and chances are Memphis probably doesn’t come that high on the list. Ahead of my own visit, out of curiosity, I Googled ‘most visited US cities’ – and it barely registered. It didn’t even feature in Forbes’ Top 30 (its nearest neighbours Nashville and St Louis did). Indeed, when I told friends I was going, one answered “Memphis, US?’ As if you could think of another – Memphis Egypt, perhaps. Memphis, Tennessee, also has its pyramid, mind. But more on that later.

I have a feeling this indifference is about to change, however. Its civil rights history aside, Memphis has soul. Quite literally. It was the cradle of Soul music. And Blues. And Rock ‘n’ Roll was born here. Music is in its DNA.

To be that much of a cultural hub during the formative years of popular music, there must be something in the water. In a way, there is; the Mississippi. America’s great thoroughfare has been transporting not just goods down its vast, fast-flowing expanse, but it served as a virtual tributary with the migration of people – and music – up from the southern country states to the big cities, with Memphis becoming the confluence of all that creativity.

On that route, on the corner of Beale and BB King Blvd (the street that Blues musicians came in on up the Delta), in the centre of downtown’s entertainment district, is The Rock n Soul Museum. Researched and developed by the Smithsonian, its purpose is to trace the origins of American music and it tells the story of how those musicians influenced the white teenagers of the ‘50s who would then develop rock ‘n’ roll. It’s a quick, potted history with some good insights into the musicians and milestones, but it is as much to understanding Memphis’s music scene as reading a synopsis on the back of a book.

To really get under its skin, you have to go the places where it evolved, and a natural first stop is Stax. Housed in the former cinema that became the Stax recording studios, the museum is a comprehensive anthology of the hugely influential and genre-defining Stax records and the evolution of Memphis Soul. After a screening of a short history of Stax with noted luminaries, you go behind the screen, and it opens up into a world of Memphis’s musical history.

The first thing you’re met with is a wooden church, Hoopers Chapel Ame from 1906, to indicate Soul’s origins in Gospel. It goes into the evolution of the ‘quartets’ in the ‘30s, defining a singing style that would evolve into Soul, running parallel to the Civil Rights movement emerging in the ‘50s, with profiles on early stars like Rufus and Carla Thomas, and musical innovators like The Memphis Horns and Booker T.

The first thing you’re met with is a wooden church, Hoopers Chapel Ame from 1906, to indicate Soul’s origins in Gospel. It goes into the evolution of the ‘quartets’ in the ‘30s, defining a singing style that would evolve into Soul, running parallel to the Civil Rights movement emerging in the ‘50s, with profiles on early stars like Rufus and Carla Thomas, and musical innovators like The Memphis Horns and Booker T.

A walk through the legendary Studio A, part of Stax’s founder Stewart’s intent to have a studio as big as a cinema to capture the acoustics, complete with the drum kits, keyboards and guitars, gets you reliving those iconic songs. These, too, are honoured in a huge floor-to-ceiling hall of fame of all the LP covers of Stax’s output and leads into yet more space crammed with memorabilia, including Isaac Hayes’ gold trimmed Chevy barking at you to ‘back off’ if you get too close.

But it’s not all historic. Stax thrives today with the Stax Music Academy, nurturing the next generation of music talent. Many of its members have gone on to the mainstream music industry, and much of that thrives in Memphis, in its beating heart, Soulsville.

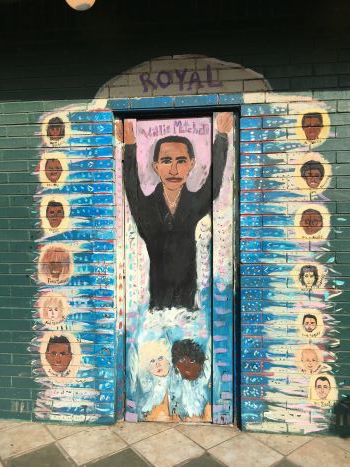

Here, studios like Royal Studios, home of Willie Mitchell’s Hi Records, now run by his granddaughter, produced classics by Al Green and Ann Peebles, and attracted artists such as Boz Scaggs and Rod Stewart, who recorded his Atlantic Crossing album here. You wouldn’t think it to look at it, an unassuming building among some lowly residences, it’s identifiable only by a hand-painted mural on the door in tribute to his artists, but it was here that Bruno Mars recorded Uptown Funk, recorded on a mixing deck from the Rolling Stones, shipped from the Bahamas.

Here, studios like Royal Studios, home of Willie Mitchell’s Hi Records, now run by his granddaughter, produced classics by Al Green and Ann Peebles, and attracted artists such as Boz Scaggs and Rod Stewart, who recorded his Atlantic Crossing album here. You wouldn’t think it to look at it, an unassuming building among some lowly residences, it’s identifiable only by a hand-painted mural on the door in tribute to his artists, but it was here that Bruno Mars recorded Uptown Funk, recorded on a mixing deck from the Rolling Stones, shipped from the Bahamas.

If London has Abbey Road as a recording landmark, Memphis has a dozen. Perhaps none more famous than Sun Studios, where Rock ‘n’ Roll was born. A small exhibition space sits above a café and shop as you enter, but it’s downstairs in the studio where during an enthusiastically-hosted tour, we get a potted history of what happened here. What’s remarkable, beyond the infamous recording of That’s All Right Mama, beyone Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash, is that the studio remains much as it was back in the ‘50s. I’m standing among giants, in the room they were born, walking the floor they did.

And so, of all of Memphis’s musical – and historical – legacy, there’s one thing I’m yet to mention. Something Memphis is perhaps known for above all else. The week before I visit, and almost the entire duration of my stay, I couldn’t get a song out of my head. “I am following the river, down the highway, through the cradle of the Civil War. I’m going to Graceland, Graceland, Memphis Tennessee…”

Memphis is, of course, the home of Elvis Presley. Fortunately, it’s not overrun as Salzburg is by Mozart, more that he’s clearly one of the city’s most famous sons. To the rest of the world, Memphis is Elvis. To Memphians, he’s a Memphian, although a pretty special one, admittedly. And so to Graceland.

It’s not what you’d expect. Actually, it’s not where you’d expect. The Graceland mansion, when it was built – and bought by Elvis – was originally in a rural spot a mile or two out of town. Now, it’s near the airport, on Route 51 (or Elvis Presley Blvd), a main thoroughfare into the city.

It exists in two parts, the mansion on one side of the road, and what is essentially a theme park on the other. There, vast hangars provide exhibition spaces dedicated to his vehicles, his time in the army, his gold discs, a whole section on his Hollywood career, 40-odd of his 80 jumpsuits, not to mention restaurants, a milkshake parlour and gift shops. Oh, and in the grounds, his private planes. On the other side is the mansion itself, a shuttle bus providing timed visits running between the two.

It’s surprisingly small, as mansions go, and the tour, guided by an iPad, can be over in an hour. Out of respect, the upstairs bedrooms are off limits, but what’s remarkable is not only that you can walk around the house, but that it has been left as it was when he died, in all its brilliant, gawdy décor. All of it, the fixtures and fittings, the TVs (14 of them throughout the house, and three in a row in the downstairs lounge), the kitchen appliances, ornaments on shelves, the green shag carpet on the walls and ceiling of the Jungle Room, furnished on a shopping spree in 1974 to remind him of Hawaii, all is as it was.

There are, too, the most extraordinary collection of artefacts; his first grade crayon box, school report cards, even the family tax return and his keys to the house. As is, of course, the relaxation area in the racquet court he commissioned, with an upright piano where, on 16th August 1977, he played a couple of songs to some close friends the day he died.

And, after all this time, still they come. In the cab back to the airport, my driver told of an English couple who’ve visited 57 times, pilgrimaging every year, sometimes twice. How do you know, I asked? ‘They call me, and I drive them around.’ Everyone has their reasons to come to Memphis, and to keep coming back.

So, what about that pyramid? That, too, is a part of Memphis’s musical history. Built as a concert venue, its acoustics were so appallingly bad, that bands that played there once, never played again. It closed, lived a short while as a sports arena, but then America’s leading fisherman, a man named Bill Dance, was approached by the owner of America’s premier outdoor pursuits stores, Bass Pro Shops, to open a new retail experience. They struck up this partnership on the strength of a bet; when the idea was mooted on a boat on the Mississippi, that they’d agree on the venture if they caught a 30lb bass, which they did.

Inside, it’s extraordinary. Essentially, it’s a swamp-themed shopping mall, with a fish-filled lake, complete with live alligators, log cabins with Spanish moss hanging from trees inside. On the floor, a range of ‘sports’ outlets (including a Beretta store and shooting range) offer everything you’d need for your outdoor pursuits. Oh, and it features the tallest free-standing elevator in the country. It’s that much of a destination there is a five star hotel with lodges inside. Dubai, be afraid.

On my last night in the city, at Earnestine & Hazel’s, a bar on South Main where legend has it Mick Jagger conceived Honky Tonk Woman, I asked my host what it is that makes Memphis different. She thought for a moment then said, ‘you know how some women are effortlessly sexy? Well, Memphis is effortlessly cool.’ I can well believe it. I visited some months ago, and it still lives with me.

Memphis may not yet feature in Forbes’ Top 30 yet, but from this year, it’s 200th anniversary, I have a feeling it’s going to be climbing.

Where to Stay

The Peabody Memphis can do stately as well as the rest of them. Known as the ‘South’s Grand Hotel’, The Peabody is a Memphis icon, opened in 1869 and listed on the US’s National Register of Historic Places, it’s also world famous for its five resident ducks, who march daily through the lobby.

The Hu. It’s about Memphians doing things their own way; the lobby is a café, the roof terrace a party venue. They say, “Stylish, singular, a little quirky and colourful, Hu. is Memphis’s new standard for Southern hospitality. Rooted in our city’s great past and with a twinkle in its eye towards a bright new future, see how we’re doing Memphis different.”

Visit Memphis from £1395 per person to include United Airlines flights (from London, Manchester, Edinburgh or Glasgow) to Memphis, four nights in The Hu or Springhill Suites, entrance to Sun Studio, Stax, Rock N Soul and Graceland. For more details, ring Bon Voyage Travel on 0800 316 0194.

For information on Memphis, please visit www.memphistravel.com.