Director Carrie Cracknell, who has worked with everyone from the Royal Court, Young Vic and National Theatre to the ENO and MET Opera, takes the driving seat of the Old Vic’s new revival of Sir Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, all the more bankable since the playwright’s recent death which has prompted a flurry of revivals offering theatre goers the chance to revisit his most notable works. But does it live up to the hype?

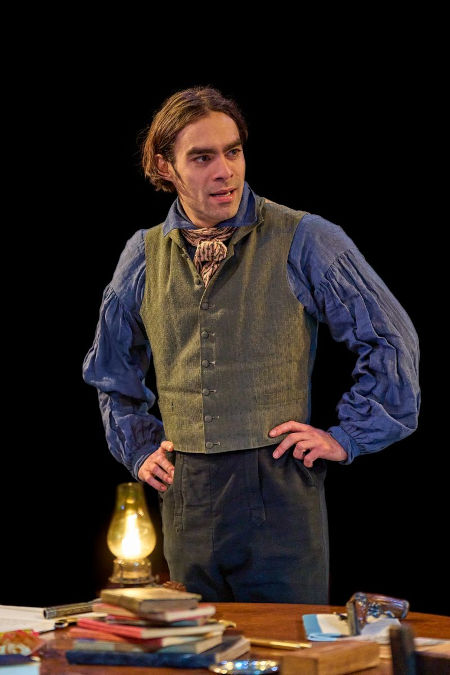

Set within the same imaginary Derbyshire estate of Sidley Park during two time periods, 1809 and the 1990s (the present day when Arcadia first premiered in 1993) Stoppard’s Arcadia, so the programme informs us, entwines “ideas, uncertainties and the beauty of modern mathematics into his dialogue and characters”; with the fictional 13-year-old aristocratic heroine Thomasina Coverly (Isis Hainsworth) not only lapping up the mathematical lessons set by her tutor Septimus Hodge (Seamus Dillane), but proving herself a child prodigy who comes up with her own theory after Septimus has taught her the classical physics of Sir Isaac Newton. Dillane is extremely fine as the Byronic, philandering Hodge, a pal of Lord Byron who thinks nothing of trysts with the wife of a guest or, for that matter, his employer’s wife and Thomasina’s mother, Lady Croom, whom Fiona Button portrays as a suitably self-centred and ditsy lady of the manor who is intimidated by her daughter’s intelligence and argues with her garden designer Richard Noakes (Gabriel Akuwudike) about his proposed hermitage.

Just as we are getting into the swing of the 19th century characters, we are introduced to two extremely arrogant academics interested in the Romantic period, Hannah Jarvis (Leila Farzad) and Bernard Nightingale (Prasanna Puwanarajah), but unfortunately the present day characters don’t convince half so much as the 19th century crew, with Punwanarajah creating the impression that he’s been cast in a bad sitcom. Hannah, engaged to the current owner of Sidley Park, Valentine Coverly (Angus Cooper), is gracious enough to put aside her anger of Bernard’s poor review of her book on Lady Caroline Lamb in order to assist him in his mission to discover the connection between some of the 19th century characters we have just seen; Valentine’s ancestor Thomasina, whose old workbook is conveniently uncovered to be interpreted by Val; her tutor Septimus Hodge; the estate’s unknown 19th-century hermit; a poet called Erza Chater (Matthew Steer), and the elusive Lord Byron, who may or may not have fought a duel at Sidley Park before absconding to Europe – and oh boy, is it irritating how much Byron is referred to whilst remaining conspicuous by his absence!

Due to this being an in-the-round production with a revolving stage, the set design by Alex Eales consists of barely more than a central table and chair, with low, encircling benches and books and other properties adding atmosphere, so too Guy Hoare’s entwined orbs of light suspended above and making reference to the scientific and mathematical topics with which the play deals. The visuals also rely heavily on the modern and period costume designs by Suzanne Cave which offer clues to the characters and allow the audience a heads up when moving between the two centuries, not least when the past and present merge.

One can blame direction as much as they like, but ultimately any production is only as good as the writing. Despite the humour, Arcadia can feel more like a Who Do You Think You Are?-style documentary intended to educate than a play designed to entertain. Not only does Stoppard flex his intellectual muscles regarding Lord Byron’s romanticism and ‘Fermat’s Last Theorem,’ a puzzle which stumped experts for over 350 years, he proceeds to give the audience a potted history of landscape garden design; Capability Brown’s idealised ‘Arcadias’ and the Romantic vision of a rural paradise that is a recreation of untamed nature. Stoppard (of course) relates this to the geometry of nature and chaos theory, furnishing us with so much detail that you could be forgiven for thinking that you were attending a university lecture rather than a play at the Old Vic. Alas, it all comes at the expense of the development of the characters and the relationships between them.

One can blame direction as much as they like, but ultimately any production is only as good as the writing. Despite the humour, Arcadia can feel more like a Who Do You Think You Are?-style documentary intended to educate than a play designed to entertain. Not only does Stoppard flex his intellectual muscles regarding Lord Byron’s romanticism and ‘Fermat’s Last Theorem,’ a puzzle which stumped experts for over 350 years, he proceeds to give the audience a potted history of landscape garden design; Capability Brown’s idealised ‘Arcadias’ and the Romantic vision of a rural paradise that is a recreation of untamed nature. Stoppard (of course) relates this to the geometry of nature and chaos theory, furnishing us with so much detail that you could be forgiven for thinking that you were attending a university lecture rather than a play at the Old Vic. Alas, it all comes at the expense of the development of the characters and the relationships between them.

Do theatre companies reviving the late Stoppard’s work imagine that critics will feel that it’s akin to speaking ill of the dead to give a poor review? Arcadia, though considered by some to be one of the finest plays of the 20th century, fails on so many levels. Waltzing between the 1990s and the 1800s, I can’t help but question whether any theatre will profit by reviving this work in the next century? It almost feels as if Stoppard, with an eye on a knighthood, sat down with the express purpose of writing a play that would go on to be studied at GCSE level. Is the dual time-scheme an intentional contrivance designed to hold the audience’s attention and deflect from a weak plot and underdeveloped characters? Stoppard also employed this format in Jumpers (1972), Indian Ink (1995) – of which there is a new revival starring Felicity Kendal – The Invention of Love (1997), The Coast of Utopia (2002) and the Olivier Award-winning Leopoldstadt (2020), his final play in which, drawing from his own heritage and the legacy of the Holocaust, he chronicled a Jewish family in Vienna across fifty years.

“If everything from the furthest planet to the smallest atom of our brain acts according to Newton’s laws of motion, what becomes of free will?” asks Septimus, when perhaps all we want to know is whether he has fallen in love with his young student. This production is rescued by the superb performances by – and the unmistakable chemistry between – Dillane and Hainsworth. Hainsworth dazzles from first to last as Thomasina; transforming from a fiercely intelligent, yet naive girl to one on the cusp of womanhood and all that this new frontier may promise. Frankly, it’s a disappointment whenever Dillane and Hainsworth are not on the stage, while their tender, beautifully choreographed waltz in the final scene is one which serves to reinforce that theatre is a platform for exploring the complexities of human relationships, not iterated algorithms, nor do the two make good bedfellows.

“If everything from the furthest planet to the smallest atom of our brain acts according to Newton’s laws of motion, what becomes of free will?” asks Septimus, when perhaps all we want to know is whether he has fallen in love with his young student. This production is rescued by the superb performances by – and the unmistakable chemistry between – Dillane and Hainsworth. Hainsworth dazzles from first to last as Thomasina; transforming from a fiercely intelligent, yet naive girl to one on the cusp of womanhood and all that this new frontier may promise. Frankly, it’s a disappointment whenever Dillane and Hainsworth are not on the stage, while their tender, beautifully choreographed waltz in the final scene is one which serves to reinforce that theatre is a platform for exploring the complexities of human relationships, not iterated algorithms, nor do the two make good bedfellows.

Make no mistake, Stoppard has not always been universally praised, with the late critic Robert Brustein describing him as a “writer without a subject” and a dramatic style akin to watching “pirouettes performed by a rather vain dancer”. Like a mathematical theory to be proved or disproved, it will be up to the individual audience member as to whether they agree with the widely-held view of Stoppard’s genius and interpret the disjointed scenes as a representation of the fractured, repeated patterns of Thomasina’s theory, or just an excuse to offer up a plot which simply does not hang together in its own right.

To my mind, the humour which is Stoppard’s forte, is undone by overly-wordy dialogue, easier to disguise during the more formal 19th century setting, yet grating when the 1990s cast have the spotlight. This is a beautifully-designed production which reminds me of a TV cookery competition in which an ambitious contestant presents a main course that is only a concoction of disparate parts and is derided by the food critics for failing to make up a cohesive dish. As in the case of Arcadia, there are simply too many ingredients and flavour profiles vying for the attention of your palate for it to be a wholly pleasurable experience.

Arcadia at The Old Vic Theatre until 21st March 2025. The running time is approximately 2 hours 50 minutes including an interval. For more information and tickets please visit the website. Production images by Manuel Harlan.