Simon McBurney. You may not know the name but you’ll certainly know the face, which is ironic for a director. That’s because we know Simon McBurney as an actor. He’s the sardonic, acerbic Archdeacon in BBC2’s Rev. But, for those of us not in the know, McBurney is also a theatre and opera impresario and here he returns to the ENO with a brand spanking new production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

It’s testament to the enduring popularity of the work that the ENO has decided on a new production barely a year after the revival of Nicholas Hytner’s celebrated turn, and that featured fifteen revivals in its 25 year span. But when you’re presented with a show like McBurney’s, how can you not? The opera is so reinvented it’s as if seeing it for the first time. So fantastical is Mozart’s fairy story that productions have scaled up and up in their renditions, with more and more elaborate sets and costumes. What McBurney’s production does, however, is to strip it right back to its component parts.

With the complexities of the story riddled with masonic and enlightenment metaphors, erroneous character layers and inexplicable plot lines, as McBurney himself says, it’s “like conducting an archaeological excavation”. So he’s gone back to the starting point, the music. If that sounds obvious, he’s done this in more ways than one. The first thing you notice as you enter the auditorium is the orchestra is in view, on a level with the stalls. As the conductor walks out and the applause ripples it seems in error that he cues the overture as the house lights are still on full. This, however, is just one way in which McBurney immerses the audience in the production. It’s the first indication that what we’re seeing is a sort of ‘deconstructed’ opera.

McBurney doesn’t just break the 4th wall but, if there were any, the 5th, 6th and 7th, too, immersing not just the audience into the orchestra, but the cast into the audience and even the orchestra into the cast. Players flap their sheet music like birds at bird-catcher Papageno’s arrival and at the point at which Tamino is given the magic flute, it’s the flautist who gives it to him, assembling it for him and then playing it when it’s required. And further layers of the production are exposed, becoming part of the design and the action. In a glass box stage right, a foley artist – the sound effects technician on a film – adds sound effects to the action in full view of the audience (occasionally out of sync and overdone for that failsafe comic effect) and, at one point, is joined by Papageno in his mildly amorous and inebriated state in Act II.

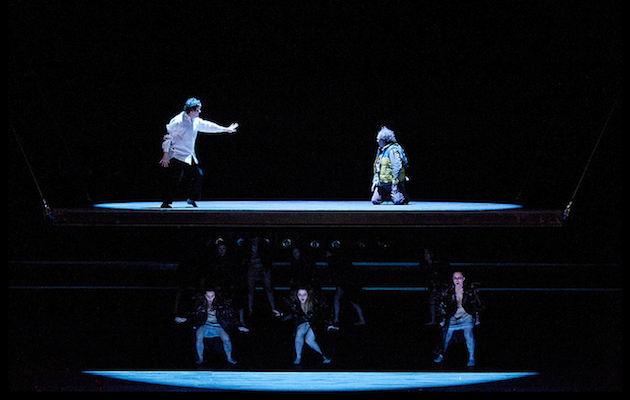

Perhaps the most striking use of laying bare these component parts is what, ironically, makes this production most visually arresting. The sets are non-existent. Instead a suspended platform adds an additional dimension to the stage, with lighting adding the emotive element. Theatre purists would applaud this, allowing much for the audience’s imagination as the platform lifts, shifts and pivots becoming a cave, a boardroom table, a mountainside.

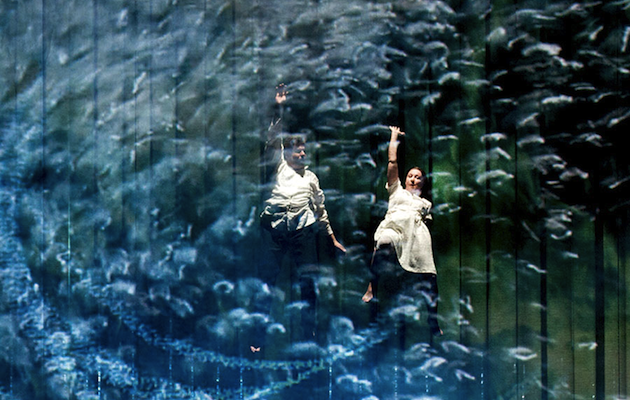

Arguably, such things are to be expected from McBurney, who’s theatre company Complicite employ visual trickery and improvisation as standard but, for all its simplicity, there’s one tool that makes this production almost cinematic: a vast screen the dimensions of the proscenium, stripping the need for backdrops. Instead scenes and set pieces are projected live, being drawn or placed in real time by an operator stage left. We’re given opening titles to the overture, concluding with mountains being chalked in front of our eyes to set the scene. It is, simply, extraordinary. So simple and yet so effective, being used comically, dramatically, and ethereally in places, providing misty backdrops, swirling whirlpools and the fires of hell as necessary.

Regardless of the visual interpretation, there is one thing that entrenches The Magic Flute’s enduring appeal, Mozart’s score. The familiar aside – the electrifying aria from the Queen of the Night (in very capable hands here with German soprano Cornelia Gotz, having played it at the Met, Glyndebourne and Berlin among many others, though challenged here to hit that high F from a wheelchair), the overture, Papageno and Pagena’s duet – what becomes apparent in this production is the music that isn’t familiar, hearing much of the score as if for the first time. In many ways that is testament to the conductor, Gergely Madaras. At just 28, and marking his ENO debut, his fluidity belies his years and, particularly being on show, his command is exemplary. It is, however, as McBurney states, about going back to the basics, back to the score. And that is where the beauty of Mozart’s genius lies.

The Magic Flute runs at the London Coliseum for just 12 performances, from Tuesday 12th November to Saturday 7th December 2013. For details of the performances dates and times, to book tickets and for and further information on the production visit the website.