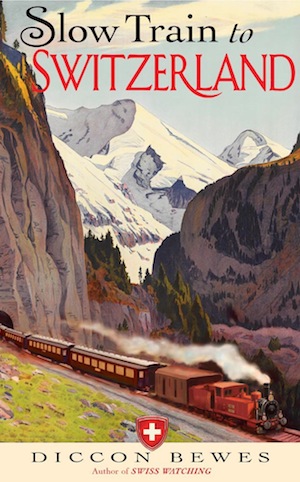

Following Larry’s trip to Switzerland retracing of the footsteps of Thomas Cook’s first conducted tour, as recorded by Victorian diarist Jemima Morrell, we a proud to offer an extract from Diccon Bewes’s Slow Train to Switzerland, in which he retraced the entire journey of the Cook-Morrell party.

Here, Diccon arrives in Interlaken, comparing the town of today with that which Jemima and Mr Cook might have encountered…

“[Interlacken] was once a truly Swiss town; it is gradually becoming a little Paris or Brussels. Fashion and gaiety find their homes here, and the pleasure-seeker will vote the town to be one of the most charming in Switzerland.”

Cook’s Tourist’s Handbook to Switzerland, 1874

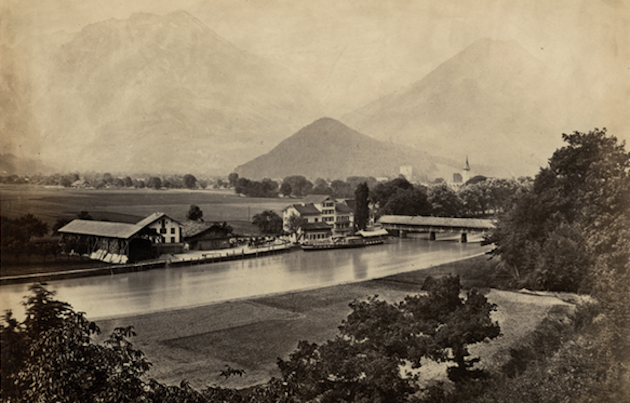

Contrary to popular belief, Swiss public transport hasn’t always been the epitome of perfect organization and immaculate timing. Back in 1863 it was very different. The railway was in its infancy, so coaches, boats or horses were the only transport methods for large parts of the country, including Interlaken. This tourist town sits astride the River Aare on a flat plain between Lakes Thun and Brienz, hence its name, although that is a recent creation – the original village was called Aarmühle but was widely known as Interlaken (variously spelt Interlacken or Interlachen) until 1891 when the name was officially changed.

It is this position between the lakes and beneath the mountains that has always made it a must-see on any tour of Switzerland. This isn’t because the town is that attractive, but for the setting and as a jumping-off point to explore the heights of the Bernese Oberland. However, before the railway arrived in 1872, reaching Interlaken involved a tranquil steamboat ride across Lake Thun followed by a chaotic coach ride into town. The steamers were too big to sail up the Aare so they docked on the lakeshore at Neuhaus, about 4km from the town centre, and unleashed their passengers into the maelstrom of carriages waiting for fares.

In his book Die Erste Eisenbahn des Berner Oberlandes (The First Railway of the Bernese Oberland), FA Volmar describes how arriving tourists were pounced on by the carriage drivers, desperate to get some of the action; those who resisted were “showered in curses”. Later, when the drivers were forbidden from leaving their carriages, they yelled to attract customers’ attention, even taking passengers for free to stop the competition earning anything. In 1870 there were 244 horse-drawn carriages (35 of them omnibuses) running the short route to Interlaken, where the only alternative was walking along the same road. That meant enduring the dust storm created by the carriages and “wading ankle-deep through the horse-shit”, as one commentator described it.

Not that taking a carriage was much better. Volmar quotes one visitor, who complains of riding “along the narrow, dangerous route … for those not sitting in the front carriage of the long procession, it was a trip in a veritable ‘Stream of Dust’, not forgetting the plague of horseflies, as well as the band of beggars.” With thousands of tourists arriving during the summer season, there was good business to be made, even if that meant bitter fighting to win it. And it was big business. In 1863 the six steamers on Lake Thun carried over 160,000 passengers, while in the summer of 1867 a total of 24,684 tourists (a quarter of them British) stayed at least one night in Interlaken. The following year saw the first English winter guests, and by 1870 there were 73 hotels and guesthouses in the town. Today there are 31.

The dusty, dirty bottleneck at Neuhaus might have served the carriage drivers well, but it couldn’t cope with the increasing numbers. A railway was the only answer and it wasn’t long in coming. The Bödelibahn from Lake Thun to Interlaken (Bödeli refers to the flat plain between the lakes) opened its first section in August 1872, running trains with double-decker carriages – the top deck was open – at 25km/h. The loudest opposition came from the carriage drivers, who weren’t objecting to the flood of tourists; they merely wanted to maintain their income stream. They all knew what progress entailed: as in Frutigen a generation later, the arrival of railway carriages meant the instant demise of the horse-drawn ones.

Double-decker trains run alongside Lake Thun to Interlaken today, though without open-top decks and with many more than three carriages. The original Bödelibahn disappeared long ago, replaced by more modern tracks, but its presence can still be noticed.

Despite only having a population of around 5,000, Interlaken has two stations, West and Ost, at opposite ends of the long main street. They are direct descendants of the two original Bödelibahn stations, relics of long-forgotten planning that survived because of another oddity: a railway that crosses the River Aare twice between the two stations for no geographical reason. The line could easily run along the south bank without any hindrance, but the planners were sneaky; they could envisage a time when the Aare might be widened in order to create a navigable canal between the two lakes.

Despite only having a population of around 5,000, Interlaken has two stations, West and Ost, at opposite ends of the long main street. They are direct descendants of the two original Bödelibahn stations, relics of long-forgotten planning that survived because of another oddity: a railway that crosses the River Aare twice between the two stations for no geographical reason. The line could easily run along the south bank without any hindrance, but the planners were sneaky; they could envisage a time when the Aare might be widened in order to create a navigable canal between the two lakes.

That would put the steamers in direct competition with their trains, and tourists could simply sail past Interlaken altogether. So they purposefully diverted the new line across the Aare and back again, a double crossing that stopped any such canal plans in their tracks.

There was once a scheme to have one grand central station in the middle of town, on the south bank of the Aare behind the line of posh hotels – convenient for tourists, inconvenient for businesses. The inhabitants around the West station, the closer to the town centre, feared “financial ruin” for their shops if that station were to move. In the end it was the impossibility of getting ships to dock beside any new central station, thanks to those two rail bridges, that saved the day. Today’s trains continue to make that unnecessary diversion and ships still cannot navigate the Aare, although canals were built to bring the ships closer to the town centre. And the two stations carry on serving their respective lakes, West for Thun and Ost for Brienz, so passengers can transfer directly from boat to train, or vice versa.

Geographical anomalies aside, the Bödelibahn is an interesting example of how and why many Swiss railways developed: tourism. In Britain and Germany, most lines were primarily built to link cities, factories, mines and ports, transporting coal, goods and workers; the railways were literally the engines of the industrial revolution.

In Switzerland that wasn’t always the case – it had no coal and small cities. Lines such as the Bödelibahn had one main purpose, to carry tourists to the mountains more efficiently. Interlaken wasn’t an important business or population hub and without tourists the line would not have been viable, at least not in the 1870s. Tourism was the blood that gave many train lines life and kept them going.

In Switzerland that wasn’t always the case – it had no coal and small cities. Lines such as the Bödelibahn had one main purpose, to carry tourists to the mountains more efficiently. Interlaken wasn’t an important business or population hub and without tourists the line would not have been viable, at least not in the 1870s. Tourism was the blood that gave many train lines life and kept them going.

The lakes and mountains of the Bernese Oberland were a prime destination, especially for the British, who came in their thousands. In these mountain regions, away from the factories and money of the cities, tourists became the primary source of income and the main reason for development. No tourism, no trains – but also no trains, no tourism (at least not in massive numbers). It was a symbiotic relationship that suited both sides.

Miss Jemima and her friends knew nothing of all that. They arrived nine years before the train on Platform 1, but cunningly managed to miss out on the unseemly scrum of carriages at the dock. Instead, they took the scenic route to Interlaken via the Lauterbrunnen valley a few miles to the south, although Mr William confessed to his father, “The scenery of the valley of Lauterbrunnen is very famous but we were so tired that we were dozing all the way.”

Diccon Bewes’s Slow Train to Switzerland is available from Amazon here and in all good bookshops.

Images courtesy of Interlaken Tourism and Thomas Cook Archive.