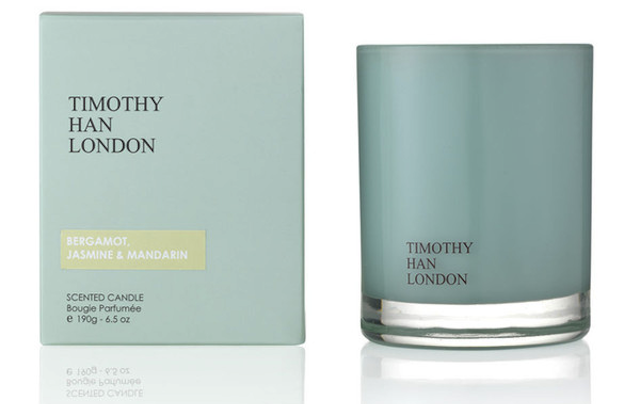

The humble candle. Classic, romantic, ambient … and carcinogenic. Sustainable luxury pioneer Timothy Han set out to clean up the industry with his all-natural, clean-burning luxury candles. Tom Bangay caught up with him in London to find out about greenwashing, globalization, and changing consumer mindsets.

You decided to make your own candles after being shocked at the environmental impact of burning a ‘traditionally made’ candle – could you tell our readers a bit more about that impact?

Candles can be harmful in two different ways. The main thing is that paraffin wax is a petroleum byproduct. If you ever burn a candle against a white wall, you get that black soot stain which is impossible to remove, you put a coat of paint on and it still comes through because it’s an oil-based soot. You’re breathing that in. The other thing is fragrance, which nobody really talks about. You don’t actually have to say what’s in a fragrance. If I have a product, in the ingredients I can just say ‘fragrance’. There are no controls. There are a lot of harmful chemicals in fragrance which get burned and released into the air.

There was a report by the BBC on a church in Maastricht which found that the air inside was 20 times over the EU limits for particular matter [a key pollutant], which is obviously what gets in your lungs and causes cancer. Granted, a church is a big space and they burn a lot of candles, but to put it in more human terms, it was more polluted than a freeway outside that had 40,000 cars travelling on it daily.

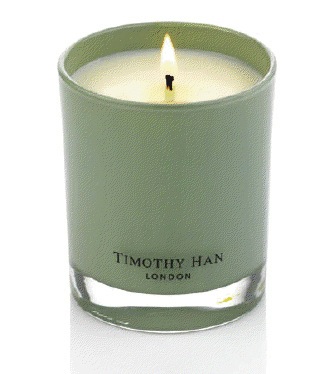

How do the beeswax and soy wax you use differ from the paraffin candles?

We’ve chosen soy wax for a couple of reasons. One is that it’s a vegetable wax, and we wanted to be as natural as possible; we didn’t want to use palm, because palm is also responsible for a lot of clear cutting, in South America and South East Asia. With the American-grown soy that we chose, it was very easy to have traceability with what we were doing. We also managed to get soy which was GMO-free and herbicide and pesticide-free. That was the main reason we did that. Then we used beeswax too because technically the beeswax helps the candle burn better.

Do sustainable materials cost more?

Do sustainable materials cost more?

It does cost me a lot to make a candle [sustainably], and I’m not making hundreds of thousands, so volumes do have a huge impact on that, but also because we chose to use essential oils, they are ridiculously expensive – you can spend £50 to get 25ml of certain oils and each of my candles has roughly 20ml of oil in it – that’s actually where most of the money goes.

When you set out to source materials that met sustainable criteria, where did you start? Did you look to ‘badging’ organisations like Fair trade?

When I started, that was still really in its infancy and they weren’t really doing much beyond chocolate and coffee. Originally I used the internet and started speaking to people, friends, getting advice, there was a lot of legwork. There still is, it’s constantly changing.

How do you feel about organisations like Fair Trade? It’s come in for criticism because sometimes it’s felt that they pay just barely above market rate, putting farmers’ wellbeing at the whims of western consumers?

I’m conflicted, to be honest with you. Fair trade or Organic labels are good because they’re a discussion point, they get consumers thinking. And it does give a certain amount of credibility for a brand. At the same time I think it is negative exactly because of the reasons you’ve said. Not by any stretch of the imagination am I saying this applies to Fair Trade, but there are a lot of organisations out there that claim to do good which aren’t necessarily doing as much good as they could be doing, given the amount of money they’re receiving.

The ‘organic’ standard is so different from country to country, what may pass as organic in the US probably wouldn’t pass as organic here. And also because I’m at the luxury end of the market, what I’m trying to do is actually build a brand that you buy because you trust it and you believe in it and that’s what we’re about, rather than because it’s fair trade or not, we’re not going to go after that kind of certification. It is a very different end of the market.

As well as the sustainability of whatever resource it might be, do you have to factor in political considerations? Obviously this is a different example but I’m thinking of things like conflict diamonds – do you have to consider factors like that?

You do with essential oils, which is quite tricky when you’re sourcing things. There are certain types of sandalwoods, for example, that you can get from some countries and not others because it might put people in danger, so yes we do have to consider that.

You do with essential oils, which is quite tricky when you’re sourcing things. There are certain types of sandalwoods, for example, that you can get from some countries and not others because it might put people in danger, so yes we do have to consider that.

One of the problems you hear about in this area is ‘greenwashing’ [the use of green PR and marketing to give the misleading impression that a product is environmentally friendly]. Is that a big problem – companies massaging their practices to meet certain standards and not others?

Oh yeah, hugely. I have a lot of friends in the clothing industry, and there’ll be factories which will completely meet the given standards, and they’ll have a back door, and there’ll be other factories shipping it in from somewhere with different conditions, and they’ll say “look, we produced this here”. And you can’t stop that, unless you have someone physically sitting at that factory 24 hours a day watching the doors. Greenwashing is a difficult one because obviously it’s not a good thing, but I think there are a lot of companies who get criticised for greenwashing who aren’t, but just don’t have the ability to manage conditions as much as they would like to.

You’ve recently started to branch out beyond candles into other products like skincare. Did that involve a whole new learning process, in terms of the materials and processes involved?

[emphatically]Oh yes. We’re launching a skincare line next year. That is harder, because it opens a whole Pandora’s box when you’re trying to deal with things that are organic and things that meet a certain standard. For example, we use clay in a cleanser, and if we want to meet organic standards we have to use a very specific type of clay, so we can’t actually use medical grade clay, which wouldn’t meet organic standards because it’s all been irradiated. So we use non-medical grade clay, which means there are a lot of bacteria – how does that bacteria then affect the rest of the product? That’s something that you can’t really control. So you have to make some really hard calls – is it better for me not to use organic, from an environmental or a health standpoint? I do actually think organic sometimes can hinder a good product. So it’s been a huge learning curve.The other problem with organic standards is that if I want to work with some small farmers in Africa, a lot of organic products need to be tactically farmed so you can monitor the farming process, and you can’t expect some small farmer who has never used pesticides or herbicides to be organically certified.

I read a quote from you in the Financial Times: ‘I want it [the brand]to last, that’s why I’m not marketing it as green’. Could you expand on that a bit?

Ultimately what we’re trying to do is to create a brand. If I’m saying that I’m green, that’s like saying ‘buy me just because I’m green’ and then when everything becomes green, then that has no more value. I think in a way the claim that you’re green almost becomes a crutch. The reality is that it’s a very small minority of customers who are green, so you’re alienating all the other consumers.

If you brand yourself as green first, then you’re appealing to the people who are probably already buying green products.

Yes, which is a small minority, and if you want to create products that are going to make a big difference, you need to sell them to more people than just that small handful. I’m trying to change people’s perceptions of what they define as a green brand. I would rather sell to a woman who actually doesn’t care about the green, but have her buy lots of green products unknowingly.

Do you think that if something was marketed as green first and luxury second, it would fail?

I think it would have a problem. Unless it was already a big established luxury brand, like Gucci is now trying to do. It’s tricky because the problem with a green product, I find, is that a lot of people made a lot of efforts to make a product green, but not to make it saleable or able to perform, and to me that’s almost worse. Fortunately it’s changing.

The idea is that it should just become accepted that that’s the way things are done rather than ‘buy this because it’s green’.

Exactly, I want you to buy my product because it’s a good product, you like the way it’s made, you think it’s good quality, aesthetically, whatever – I don’t want you to buy it because it’s green. You’re always making decisions, is it better for the environment, or is it better for people? It’s better for the environment in one way, it’s worse for the environment in another. This is what makes it so difficult, because it isn’t binary, you have to make choices.

Exactly, I want you to buy my product because it’s a good product, you like the way it’s made, you think it’s good quality, aesthetically, whatever – I don’t want you to buy it because it’s green. You’re always making decisions, is it better for the environment, or is it better for people? It’s better for the environment in one way, it’s worse for the environment in another. This is what makes it so difficult, because it isn’t binary, you have to make choices.

The dream, long-term, would be that the whole luxury sector takes sustainability into account when making a product. Which luxury products would you say offer the biggest challenge in terms of becoming sustainable?

I think in a lot of ways the luxury sector doesn’t need to make as many changes as some people think. Some people think of the luxury market as extravagant, but if you think about it, what was luxury originally? Materials, craftsmanship, design; a good quality watch would last you a very long time. The problem now is with fast fashion, luxury is still a small market. The luxury market has lost a lot of its green credentials, in the ’80s when it became much more of a brand than a product, but it’s a filter, it filters downwards.

Do you think there’s an increasing appetite for green products lower down in the market, after things like the Bangladesh factory collapse?

I think publicly, in terms of public awareness, there’s an increase. I think in reality people will always buy cheap products. Lucy Seigle had this fact: if you ask, 80% of people will tell you they’re concerned about green and environmental issues, but in terms of reality it’s about 8% of that 80 who’ll actually put their money there. And that’s a big problem. That’s why I think we just have to make it all as green as possible.

A noble aim. And hopefully a profitable one. Thank you Timothy!

Thank you.

For more information about Timothy Han and his exquisite products, visit his website.