Terence Rattigan wrote Man and Boy in 1961, at what he perceived to be the nadir of his career. Where the old guard of Gielgud and Olivier had embraced the new wave emanating from the Royal Court, it proved more challenging for Rattigan as a writer to reconcile himself with the era of Osborne and Look Back in Anger. This was meant to be his challenger to that movement, deliberately ‘modish’ and confrontational, but it only afforded a limited London run (fairing marginally better on Broadway), signifying how he’d fallen from fashion. Since then, it has had precious few revivals, most notably with David Suchet twenty years ago. It deserves far greater attention.

Set in 1934 in a shabby Greenwich Village apartment, the play centres on Gregor Antonescu, a Romanian financier whose empire is collapsing. Desperate to salvage his crumbling business, he seeks refuge with his estranged son Basil, a struggling pianist, hoping to use the apartment as a base for one final deal. What follows is a chilling demonstration of manipulation as Antonescu gradually seduces both the businessman Mark Herries and his loyal associate David Beeston into a web of corruption and betrayal, exploiting everyone in his path — including his own son.

As you can tell, the play resonates powerfully today. In an era defined by crypto crashes, corporate malfeasance, and the spectacle of vast wealth built on dubious foundations, Rattigan’s examination of corrupt power and the ruthless accumulation of riches feels unnervingly prescient. The character of Antonescu (based on the Swedish Match King Ivar Kreuger and the Anglo-American investor Samuel Insull, incidentally) anticipates the Bernie Madoffs, Robert Maxwells, and others we may not wish to mention.

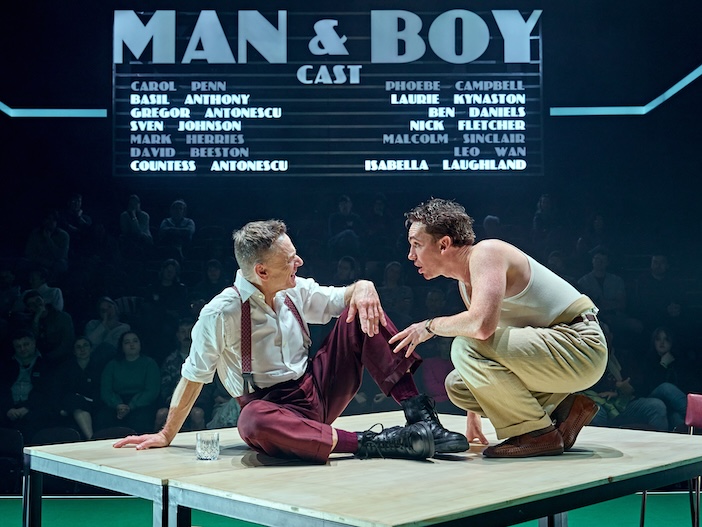

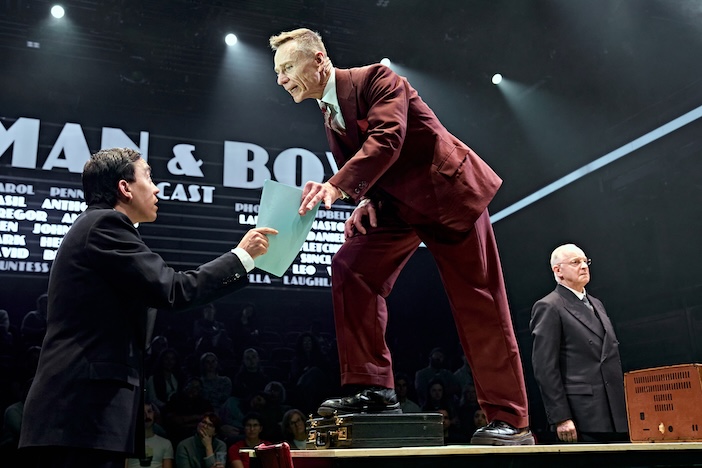

As a story, it is testament to Rattigan’s craft. The gradual manipulation of Herries and Beeston by Antonescu is given a sinister, almost reptilian edge by Ben Daniels, and one does feel inexorably drawn in as the plot unfolds. “Gripping, isn’t it,” I heard as I came out for the interval, and the description is apt. At times, the production slips into melodrama, with exaggerated movement — Suchet’s interpretation, I understand, was played far more straight — but it is very much aided by the supporting cast. Malcolm Sinclair, as the seduced Mark Herries, gauges it perfectly, as does Leo Wan as the squeaky-voiced Beeston, and Laurie Kynaston as Antonescu’s estranged, duped son. It is with him the audience’s sympathies lie; spurned yet accepted at the turn of a dime, his emotional journey mirroring how he, too, is ‘played’ by his father with the same cold calculation applied to every business deal.

Being staged at the Dorfman, the production is performed in the round, which immediately thrusts it into a more contemporary space. It makes for a minimalistic setting, but there are stylistic flourishes reminiscent of a film set in the 1930s: the cast are displayed in the manner of a thirties billing above the stage, each name lighting up when they appear in the action; the lighting gantry is used to some effect to close in on the drama; and subtle, distant tympanic sound effects emerge against the dialogue, heightening the tension as an incidental score.

But there is one stylistic decision that jars — and jars distinctly. Tables occupy the centre of the room and are moved to denote the apartment’s space accordingly, but they are also climbed upon with no rhyme or reason as to why. Clearly, it is to demonstrate power, from height, who is taking over whom at any turn, but they become a distraction, an unnecessary gimmick. It is a quibble, however. Anthony Lau’s direction — and these performances — really draw the best from Rattigan’s script.

Rattigan wrote to his producer, Hugh ‘Binkie’ Beaumont, at the time, clearly feeling the pressure that, were it not to be produced, he was resigning himself that it might be ‘read by some historian in 50 years’ time and pronounced as the best work of a fashionable contemporary dramatist, never produced in his lifetime.’ It has been produced and, 65 years later, with the benefit of hindsight and considering his oeuvre, Man and Boy shows its colours. The work of a craftsman, it deserves its place. This is compelling writing that resonates more powerfully today than it ever did during Rattigan’s lifetime.

Man and Boy runs at the Dorfman Theatre, National Theatre until 14 March 2026. For more information, and for tickets, please visit www.nationaltheatre.org.uk.