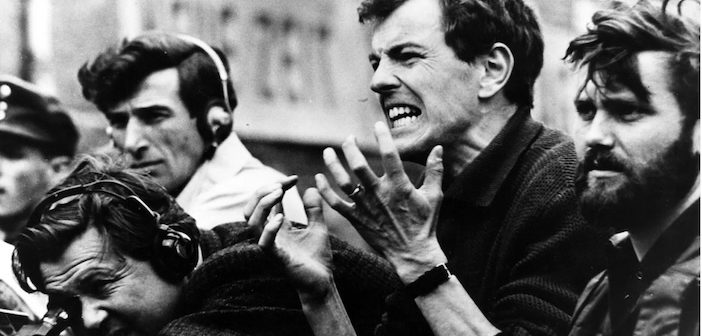

In a follow-up to his polemic on the BBC licence fee, former television director Paul Joyce turns to the career of Peter Watkins — a radical filmmaker nurtured, resisted, and ultimately sidelined by the Corporation. Through personal experience and cultural history, Joyce asks what British broadcasting lost when it failed to make room for the auteur…

The BBC has many “lost” works: tapes and film reels destroyed during rounds of clear-outs and restructures. Some occasionally resurface from an attic or garage, and much is then made of them when they do. But two films from its archive have recently appeared on iPlayer with almost no fanfare. Not because they were lost, but because, arguably, it was the filmmaker himself who was quietly destroyed.

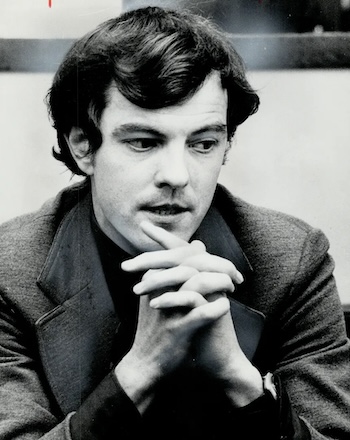

So, this article is about setting the record straight about the systematic destruction of a creative genius the BBC had unwillingly and unwittingly nourished — one that many of you may never have heard of.

The Harvard University Film Archive puts it perfectly:

“There is a strong case to be made that Peter Watkins is the most neglected major filmmaker at work today. Over forty years the British-born director has managed, against trying and often adversarial circumstances, to produce a highly original and powerful body of work that engages the worlds of politics, art, history and literature. That these films remain obscure is a function of suppression by producers, weak-kneed distributors, surprisingly hostile critics, and the filmmaker’s own legendary iconoclasm.”

Not only will you probably never have heard of him; you will almost certainly never have seen his films, apart from the first two he made for the BBC. The rest were largely produced for critically underfunded European broadcasters, independents, and loosely formed collectives. His masterpiece on the painter Edvard Munch — running 221 minutes even in truncated form — has never, to my knowledge, been shown on British television.

Not only will you probably never have heard of him; you will almost certainly never have seen his films, apart from the first two he made for the BBC. The rest were largely produced for critically underfunded European broadcasters, independents, and loosely formed collectives. His masterpiece on the painter Edvard Munch — running 221 minutes even in truncated form — has never, to my knowledge, been shown on British television.

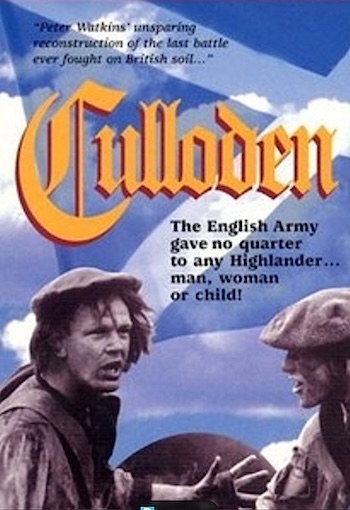

Culloden (BBC, 1964) was widely seen as a genre-defying, trail-blazing work which should have propelled Watkins, aged just 24, to the very top of his profession, proving that it was possible to be an auteur even within the restricted limits of the small screen. Just days after I penned my diatribe against the licence fee in these very pages, the BBC quietly transmitted Culloden late one night on BBC Four, with no fanfare at all.

Made on a shoestring budget, without a house-trained producer in attendance — thankfully relieving Watkins of the need to explain himself — it allowed him to claim rightful credit as both conceiver and director. The film is a supra-graphic depiction of the wholesale slaughter of generations of Highlanders at the Battle of Culloden and the subsequent destruction of an entire culture. Though hailed at the time as an English victory, any cerebral Englishman or woman should hang their head in shame at its contemplation. Watkins’ film was widely interpreted as a direct attack on the establishment itself.

For the first time, Watkins assumed that a camera was present at the battle, with an enquiring reporter — heard but not seen — interrogating participants at key moments during the action. This technique is commonplace now, but was utterly revolutionary then. He also cast amateurs in key roles, including descendants of survivors, even in the role of Bonnie Prince Charlie himself.

Watkins believed television should reflect the social groups comprising our confused hierarchies — predicated on access, information, and education — rather than a diet of soap operas and endlessly funded thrillers. He died last year, undoubtedly disillusioned and exhausted by a culture awash with bubblegum series and infinite budgets.

The term auteur has never truly taken hold in television, unlike its bigger brother, cinema. I say this as someone who tried — bloodied but not unbowed — during my own time at the BBC in the 1980s, when I was briefly allowed to co-write, cast, and direct a four-part Doctor Who story. But that is a story for another time.

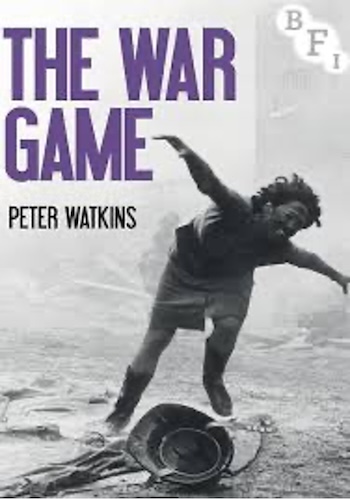

Watkins’ second BBC film, The War Game, brought him both an Academy Award and decades of humiliation. This astonishing pseudo-documentary, depicting the aftermath of a nuclear attack, was instantly branded “untransmittable”. I genuinely believe the BBC would have reduced the negative to ashes had pirated copies not escaped the vaults of Television Centre. It would be thirty years before the film was finally shown on British television. Watkins’ desire to depict the absolute horror of nuclear conflict was deemed too horrifying to show anyone — a cruel irony if ever there was one.

Watkins’ second BBC film, The War Game, brought him both an Academy Award and decades of humiliation. This astonishing pseudo-documentary, depicting the aftermath of a nuclear attack, was instantly branded “untransmittable”. I genuinely believe the BBC would have reduced the negative to ashes had pirated copies not escaped the vaults of Television Centre. It would be thirty years before the film was finally shown on British television. Watkins’ desire to depict the absolute horror of nuclear conflict was deemed too horrifying to show anyone — a cruel irony if ever there was one.

At this point I must declare an interest. The legendary editor Mike Bradsell — who cut Culloden and The War Game — spent the latter decades of his career editing my own documentaries. I suggested he re-establish contact with Watkins, whom he had not spoken to in thirty years. This led to Peter visiting me at my Soho offices.

He had recently completed Edvard Munch, and I hoped to entice him back to the UK to complete a new project under my expanding banner of films on filmmakers and composers. Why our negotiations eventually foundered I can no longer quite recall, but the truth is that Peter never produced a proposal I could, in all conscience, take to a broadcaster — even the then-experimental Channel 4. With regret, we went our separate ways, and thereafter neither Mike nor I ever heard from him again.

To be fair to the BBC, Watkins’ exile cannot be laid entirely at their door. His first feature film, Privilege, rapidly drove him from British shores when a cinema executive refused to distribute it widely, objecting strongly to its politics.

To be fair to the BBC, Watkins’ exile cannot be laid entirely at their door. His first feature film, Privilege, rapidly drove him from British shores when a cinema executive refused to distribute it widely, objecting strongly to its politics.

Had Peter Watkins — as with that other renegade auteur, Orson Welles — died young, he might have been canonised like Mozart or Dylan Thomas. Instead, both lived long enough to witness the slow erosion of what might have been. Welles retreated into magic acts; Watkins into underfunded documentaries and unfinished social experiments.

That these films now exist quietly on the BBC’s own platform, unannounced and largely uncommented upon, is a small irony not without its own justice. The institution that once silenced Watkins now preserves him — albeit too late, and all too softly. Rest in peace, Peter. And may those who curtailed your talents reflect, eternally, on what British broadcasting lost.

Culloden, The Making of Culloden, and The War Game are currently available on BBC iPlayer.