In June 1863, a Victorian diarist and six companions set off from London on holiday. Their destination was Lucerne in Switzerland to what had become the vogue attraction of its day, watching the sunrise from Mount Rigi. 150 years later, Larry joined an exhibition group celebrating and recreating that journey…

It’s not widely known but among their other achievements in the 19th century the British built Switzerland. Not the country, obviously, but to all intents and purposes set it on a course that has defined what it is today. As conceited as that sounds, it’s broadly true. It’s hard to believe now but in 1850 Switzerland was an impoverished subsistent community; we’re talking pre-banks, pre-watches, pre-chocolate – though there was cheese, admittedly. They did, however, have one natural resource which would encourage travel to the country and thereby set its fortunes running: mountains.

Mountains provided fresh air, challenging walks, recuperative springs and death-defying faces to try and climb (the Alpine Club was established in 1857). More importantly, mountains provide stunning vistas and there was one mountain that was considered the queen of them all where views were concerned: Rigi. It’s odd to think now, since Rigi is little-known. We define mountains by height and by demeanour. Hence, the Matterhorn, the Eiger, all get better press. But, to Victorians, Rigi was the place to go, surrounded by shimmering lakes as it was, valley clefts receding into the distance and a spectacular view of the sunset rising over its taller cousins in the east. It became the destination for discerning Brits to visit, witness and tell all their friends about. It also happened to be a summit that was the most achievable to the intrepid tourist, including, no less, Queen Victoria, albeit her ascent to the summit was achieved in a sedan chair.

Tourism to Switzerland at the time, if there was such a thing, was the preserve of the upper classes. Spending a ‘season’ in Interlaken, for example, taking tea at the Victoria hotel (still there) or promenading its streets, became an essential part of the scene, to be seen in. What enabled this is what had enabled travel all over Britain and Europe; the railway. But while it was revolutionising the world, its slow adoption in Switzerland had hindered the country’s progress. Again, it seems hard to imagine now but, politically, peace-loving Switzerland was a country plagued by parochial bureaucracy with its division of cantons; it’s ironic that Switzerland had its first train station built some two years before a railway line got near it for all of the disputes over who might own the line.

Then, in 1863, something momentous happened. Something that would change the country’s fortunes by creating the demand for railways that would fuel its development into the singularly wealthy and desirable destination we know today. A middle-class Englishman went there on holiday. His name was Thomas Cook.

Purveyor of package tours, Cook had already established a solid business escorting hundreds at a time into the Highlands of Scotland. The popularity of Rigi had got him thinking that he might be able to do the same through mainland Europe, but with one ground-breaking concept: an all-inclusive ticket. It required brokering deals with passenger steamers, rail companies and hostelries, taking the hassle out of travel, from crossing borders to foreign currency exchange and paving the way for generations of English not to have to speak in a foreign language and thereby antagonising the local populations ever since.

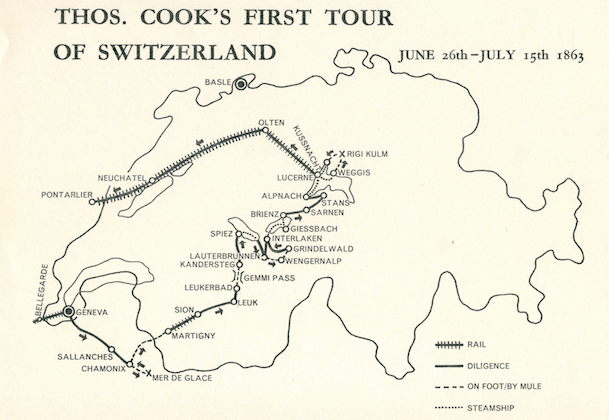

To do so, he required a research trip so he placed an advert in his company’s travel magazine, The Excursionist – pioneer, he was, in more ways than one; Conde Nast eat your heart out – calling for fellow travellers and soon set off for Paris with 120 people in tow. It sounds horrific to us now, but these were cutting-edge concepts in their day, and still only the preserve of the rising middle classes. Fortunately, by the time the group got to Geneva – our starting point 150 years later – the numbers had dwindled to a more manageable sixty. And by the time they left Geneva, their group had split yet further, into thirty, and those in three separate parties. Cook joined one of those groups, calling themselves the Junior United Alpine Club, among whom was a Miss Jemima Morrell, whose diary of the trip proved to be the account of this historic journey.

We were a far more cumbersome twenty. To mark the anniversary, it seemed no-one should be left out; journalists, travel writers, tourist board reps, competition winners, Thomas Cook’s archivist, a modern day Jemima, even Morrell’s descendants joined the party, recreating this historic voyage. Our modern day Cook was the man who has written the book on contemporary Switzerland. Literally. Diccon Bewes’s Swiss Watching is a best-seller, even in Switzerland, telling the Swiss a few things about themselves. Diccon was our guide and qualified in more ways than one, for he had recreated Miss Jemima’s journey two years earlier for his follow-up book, fittingly entitled Slow Train to Switzerland.

Travelling from Geneva, the Junior United Alpine Club went ‘by diligence’ back into France, over the Mer de Glace, then Martigny, Sion, Leukerbad, over the Gemmi Pass to Kandersteg, through Spiez, up to Grindelwald, to Interlaken, Giessbach, Brienz and, eventually, Lucerne, before hiking up Rigi. Where possible our route – and even the mode of transport – was the same as that of the Cook-Morrell party, though in 150 years the Swiss have somewhat raised their game in the rail travel department, now covering over 5000km of track to precision timing making much of our passage to Rigi swift by comparison. Elsewhere, they – and we – would take a paddle steamer across lakes, a hackney carriage (ours was an indulgence in Interlaken, theirs a necessity), ascend the 2348m Gemmi Pass on foot (though only our modern-day Jemima, herself an experienced hiker, managed the walk – we took the cable car), descend on horseback and even, for those that wished it, a ride in a horse-drawn sedan.

In as much as our route and the manner in which we travelled may have been similar, we, of course, were blessed with 21st century comforts. Notably, appropriate clothing. With much of the trip taken on foot, crossing the Daubensee following icy tracks and slippery paths even in June, we were fortunate for a sturdy pair of boots. A jaunt across a glacier, even hiking the Gemmi, undertaken in layers of crinoline, could hardly be considered part of a holiday in 1863.

In as much as our route and the manner in which we travelled may have been similar, we, of course, were blessed with 21st century comforts. Notably, appropriate clothing. With much of the trip taken on foot, crossing the Daubensee following icy tracks and slippery paths even in June, we were fortunate for a sturdy pair of boots. A jaunt across a glacier, even hiking the Gemmi, undertaken in layers of crinoline, could hardly be considered part of a holiday in 1863.

Generational differences aside, our intent was to experience as much of what they might have experienced as was possible, though this proved tricky when it came to our accommodation, for not many of the hotels of Miss Jemima’s day remained standing. It became rather an amusing recurrence through our trip to learn that nearly every hotel we’d intended to stay in had burned to the ground, though more from the period’s use of candles and lamps than for any bent the Swiss might have towards arson.