It’s Sunday fiction and we have the first part of a short story from Arb regular Harry Chapman. Cut off in a wintry wilderness, Louis and his faithful hound, Loupo, are running out of options…

Louis had decided that the dog would have to die. He had assiduously avoided the prospect as being vile and treacherous (what, kill his own dog?) but it had suddenly dropped into his mind hard and polished, immoveable, inevitable. It has become a platitude (but true for all that) that dog is man’s best friend, and it has often been said that there is no greater gift a man can give than to lay down his life for a friend. The dog would die so that the man could live. There could be no greater expression of its love and fealty.

The weather had closed in suddenly. One moment it was clear and bright with a high winter sun warming the granite outcrops and melting the crystalised dew on the reindeer lichen, the next a sinister grey pall had stretched itself across the Heavens. There had already been snow lying in folds on the high ground; the ground was hard and speckled with frost. But now it blew in great choking drifts that stung the eyes and spun you in confusion. The man and his dog had retreated to the nearby cabin for shelter. He had known blizzards before and the best thing to do was to hunker down and to let it blow itself out. It might last a few hours or a couple of days. This one had lasted a week and there was still no sign that it was easing. It was as if nature was testing him, mocking him for his knowledge and forbearance. The place they were in was known as ‘La Poche de Dieu’ to the locals and wearily he registered the irony. But in his heart, sometimes erupting into voluble sputterings, he cursed his Maker. Someone had to be to blame.

After the first night they had become snowed in. The next morning he had to climb out through a window to unblock the door. After this he would emerge at regular intervals to clear a passage from the threshold. By the third day the snow had reached the level of the windows and was pressing hard against the glass. Thereafter he had to shovel this free as well to avoid being completely buried.

There was an open fire in the hut, the chimney lined with sheet steel, and there was enough wood in the store for the first four days. After this he would gather from the surrounding trees, snapping off the dead and mostly dry lower branches and bundling them into faggots to take back. The hard larch sap would spit and fume fiercely when ignited and the dark woodsmoke was pungent and heady. It smelled good.

He would melt snow suspended in an old billy can over the fire, and by this method would produce enough liquid to slake their thirst. The problem was food. Thinking that they’d be gone for a couple of days, he had packed abstemiously for three, including dog food. Even with careful rationing by the end of the week the supplies were long gone, apart from a single bar of chocolate. Man and dog were wasted and forlorn. They eyed each other pathetically, seeking some small grain of hope or inspiration from the other. Apart from the crackle and hiss of the fire and the soft patter of snow flurries occasionally hurled against the window panes, the only sounds were the whine and pop of their groaning bellies. They were beginning to devour themselves.

Louis stared at the fire. He would try and lose himself in the flames. Sometimes it would work. He would enter into a sort of trance where all he would see were the flickering jumping fingers of light. He would become one of them – dancing, twirling, hot and bright but without substance. Time would stretch, loosen. Nothing mattered but the dance and that would last for eternity. And then something would break his concentration. Some distraction would crack and reality would come tumbling back. He would begin to feel cold on his neck and back and the gnawing pangs of hunger would begin again.

He looked at his dog. Its eyes glistened, and the fire danced in them too, like tiny exploding suns, fracturing red dwarfs in the hollow black space of the cabin. There was an appeal in them too that cut ice into the man’s heart. The animal still looked to him. He was the master, the captain and the king. He would get them out of this. He would solve the riddle. But Louis knew this wasn’t so. He hadn’t told a soul where they were going. He had been a fool and was paying the price. There was nothing more he could do.

The dog continued to gaze at him. He had only experienced the depth and intensity of that look once before. Then it had been a girl and it had seared him. He had walked away. It was the same look of total love without reason or condition. It was unbearable. He wanted to cry or run from it, as he had the last time. There was nothing love could do to save them.

He looked in on himself, searched for that sickening thought and plucked it from the shadows. The dog would have to die. And he swiftly added the appendix – but it would die out of love. The love would continue – in fact it would attain its most elevated form. Self sacrifice. He was pleased with this now. He was convinced. He thought finally he could do it. Yes, he could do it.

He refocused his eyes and was startled to find that the dog had vanished. He nearly swept his hand through the air to search for it. But it hadn’t moved. But something had changed so wholely in the nature of the animal to render it, for a few moments, invisible. The glow had gone out of its eyes. They were blank. They were the eyes of any animal – guarded, veiled.

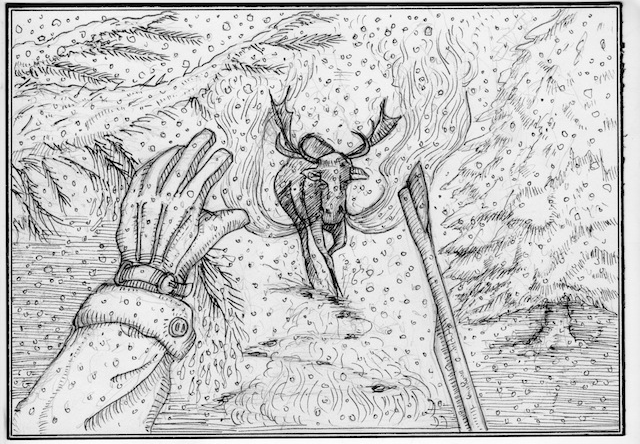

There was a noise outside; a scratching, then a bang as though something had collided with the wall of the dwelling. The dog pricked up its ears and bobbed its head to the sound. The man turned. He picked the rifle off his knees and stepped to the window. It was almost opaque from grime and frozen condensation. He used the bunched cuff of his coat to clear a small aperture, and peered through. Snow was blowing in from every conceivable angle – spiralling, spilling, winnowing. The dark trunks of the trees and the underside of the fir canopy were just about recognisable as fluttering shadows. What may have been the fresh tracks of an animal led away from the hut. Louis thought he saw something scampering away into the gloom.

He pulled on his fur hat and gloves and turned excitedly, hopefully to the dog,“ Allez viens, mon chien!”

But the dog didn’t move. It merely continued to look at him, ears pricked, with that same unreadable expression. He repeated the words, toning them into a command, but still it wouldn’t come. It was only when he flung the door open and was about to step out that the animal quietly padded up. But still it wouldn’t cross the threshold. The man concluded that hunger had sapped its spirit.

He banged shut the door and stepped from the shelter of the porch. Immediately the snow whirled in to sting his cheeks and eyes, like a thousand ice-sharp midges. It was the worse he had known it. A white tumult.

He crouched down, shielded his face and scanned the ground for tracks. He picked something up, but they were so obscured it was impossible to say what they belonged to. He could just about follow them, back through the trees, out into the forest.

He was an experienced woodsman and had been stepping over boulder and up shaded rise since he was a boy. The rifle was for deer and hunting them had become more than a pastime. It was a passion. He would come out for days at a time, sometimes longer, bivouacking under the trees or staying in one of the huts that were scattered over the hillsides. Formerly he had come alone, but since rearing the dog to young adult it had always accompanied him. “Loupo” he had named it a little unimaginatively, but how apt the name became. It was as intelligent and tenacious as its namesake. An instinctive hunter, as quiet and alert as the forests that it stalked.

Louis knew after the first day that the deer were all gone, hunkering down under a mesh of low boughs, peppered with snow, as drab and still as damp bracken, only the slow twitch of an eye and a quiver of a flank betraying them. The hunt was over anyhow; they couldn’t even find their way back along the trail. Mere survival was the thing now. Still, he would step out everyday with the gun, before clearing the threshold and gathering firewood, in the hope of taking a bird, a winter rabbit, or even a rodent of some sort. But there was nothing. Everyday, not a single living thing. And now this! If he could move fast and the creature had not travelled far – which it probably wouldn’t have done in these conditions – there was a chance. A strong chance! He was a good shot. Had he really considered killing to eat his own dog – the animal he had fed and trained and loved, and that had loved him back, above all things? He tried to push the thought out before it disabled him, but succeeded only in pushing it beneath a dirty jumble of other thoughts which once conjured and found repulsive, refused to leave.

Cocking his rifle, he moved as swiftly as he could along the line of disintegrating tracks, using his free hand to brush aside the dangling fir branches. He sank to his knees, beyond his boot tops. Ordinarily the dog would have guided his steps or he would have used a stick to test the ground. But there was no time for precautions, or so he told himself. Hunger and desperation had made him careless.

His breath curved out in great snorting plumes. It was hard going and the air was thin where they were. It burned his lungs taken in such big gulps. He felt weak, had it.

He leaned over and placed his mittened hands on his knees to steady his breathing. With a start he saw that the tracks had stopped. He must have blundered past the point they turned off. Either that or the animal had paused behind him, was crouching amongst the undergrowth, nose twitching the air for scent, watching.

He strained to listen but could hear nothing but his breath coming in shortening sighs, magnified by his muffled ears. He undid the flaps and tied them up. Immediately he felt the chill of the air like a slap. His ears tingled. The cold made him alert.

He raised his rifle and squinted back into the gloom. The snow continued to fall thick and fast. It foreshortened distance, played with perspective. The great whiteness seemed to dilate, as though it were part of some massive pulse. Everything seemed to creak.

He was stepping back, feeling out the holes he had made in the snow for ease of movement. There was a thatch of branches and undergrowth that had his attention, cross-hatched against the paleness. He narrowed his eyes to slits, attempted to force them through the intervening distance, past the veils of moving snow, through the interlocked tendrils of vine and larch root, at the shifting mass beyond. It seemed to waver and recede, bleeding into the whiteness of the surrounds. Then a glistening sheen. White in white. The remotest glint. It was an eye.

Louis heard himself utter a cry. It was loud, startling. He fumbled with his gun, looking down at his hands. The catch was on. He must have inadvertently slid it back. There was a thunderous crashing. It sounded as thought the earth was being rent apart. He slipped the catch open. There was a deep bellow that shook him with its vibrations. A sheet of hot breath clouded the air. It was warm and sickly and stank of wild animal. And then the eye again, closer this time, almost on top of him, white and rolling, mad with fear and fury.

He faultered, lurched. The gun went off, recoiled. There was a deafening roar that squashed his senses and filled his ears with splinters of echoing shrillness. He stepped back and felt the galloping impact of something hot, muscular and inhuman. He felt his coat shred. There was a piercing pain in his arm that was so sudden and fleeting that instinctively he knew it must be bad. He sensed without doubt that this must be the end, but felt so unprepared, so cheated in the timing that he clung on in himself, fought desperately to reverse the decision.

He hit the ground with a wallop that winded him but almost immediately was cascading down amongst snow and debris. He felt powerless, like a child in an adult’s world, but there was nothing he could do. He gave over to utter resignation spiced by a sickening sense of enjoyment. Just when he had persuaded himself of this state he ploughed into the ground with a heavy thud.

He lay where he had fallen, on his back, with his right leg twisted under him. Snow was shedding directly onto him, fluttering down like millions of tiny descending moths. It was enchanting, lulling, and a view he had never seen before. He knew he was hurt, but didn’t know how badly. He didn’t have the will to start picking over his injuries, or looking to the practicalities of the situation. He was bored of the responsibility of life. He wondered how long he could just lie there.

‘Le Meilleur Ami de L’Homme’ continues next Sunday…